Printmakers address globalization at UB Anderson Gallery

by Jack Foran

Where We Are

Three printmakers with area ties but interests extending from local to global are on exhibit at the UB Anderson Gallery. The three artists are: Kevin B. O’Callahan, who around the 1930s and 1940s specialized in prints and drawings of the Buffalo industrial scene, particularly the waterfront, grain elevators, shipping; Harold L. Cohen, retired head of the UB School of Architecture and Planning, a printmaker in a wide variety of media and styles; and Chunwoo Nam, who earned his MFA from UB, and whose work, which includes printmaking, performance art, video, and sculpture, explores the problematic matter of globalization.

Three printmakers with area ties but interests extending from local to global are on exhibit at the UB Anderson Gallery. The three artists are: Kevin B. O’Callahan, who around the 1930s and 1940s specialized in prints and drawings of the Buffalo industrial scene, particularly the waterfront, grain elevators, shipping; Harold L. Cohen, retired head of the UB School of Architecture and Planning, a printmaker in a wide variety of media and styles; and Chunwoo Nam, who earned his MFA from UB, and whose work, which includes printmaking, performance art, video, and sculpture, explores the problematic matter of globalization.

Chunwoo Nam’s provides little by way of remedy to the ills and injuries of globalization, but seems to ask a key question—over and over, until we start to take it seriously—namely, where are we, really, within the globalization scheme that seems to simplify the world political/economic structure, to be intended to simplify, but more likely complicates, and makes for increased large-scale exploitation of the pawns in the system by the players. Whereas globalization was originally imagined as creating “a global village,” the artist says in a written statement, “the current world is more like a network of global cities, densely composed of unbalanced social classes.” Originally considered a way to minimize national border barriers to economic prosperity, when have national borders been such a burning political issue? When have issues of immigration and migrant labor—a form of economic exploitation not much different in effect from slavery—been so prominent in the public so-called discourse in this country and other have versus have-not nations?

Numerous of the specifically print works and several videos of performance pieces are called I Am Here. The prints show variations on a panoramic view of Times Square, replete high above with garish billboard advertisements evoking the world economy—brand names like Toshiba, Swatch, Levi’s, Chevrolet, the show The Lion King—and at ground level, like some thick-sown agricultural crop, what could be a distant perspective view of the kind of shoulder-to-shoulder human morass that sometimes crowds into Times Square, but in this case also stretching down Broadway and Seventh Avenue to infinity, and foreground large shadow image of an individual human, likely the artist.

The performance piece videos show the artist in the flesh in central city areas in several world cities silently, repeatedly, painting on the pavement the words “I am here,” while passersby completely ignore him or notice and ignore him. (In big cities, people do strange things. In a village, there’d be some reaction.)

A red neon sign located at the entryway to the exhibit seems to pretty much sum up the artist’s idea about globalization. It reads, “By the money/For the money/Of the money.”

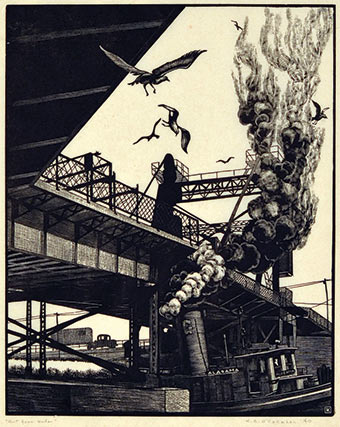

Kevin B. O’Callahan’s muscular depictions of the waterfront and associated apparatus occupy a territory between technical drawings—absolutely nothing denigrative implied by this reference to an art category invented and perfected by none less than Leonardo da Vinci—and abstractive meditations on pure form.

Especially interesting are several examples of pencil preliminary sketches and associated finished prints, in one case together with an old photo of the sketch and print subject, namely, a raised enclosed conveyer system, including two incorporated wooden work station shacks, above a vehicle passageway. Another preliminary sketch is of the old—not the current—Ohio Street Bridge, seen from below, near water level, from an oblique angle perspective. The more dramatic finished print features a tug emerging from under the bridge, spewing black smoke, gulls spiraling above.

In addition to the Buffalo waterfront works, there are a series of marvelous illustrations of various steps along the way in the intricate technological process of wooden shipbuilding. These works were done at a facility in Thomaston, Maine.

This exhibit would have been a welcome adjunct to the recent National Trust for Historic Preservation conference, with its special attention paid to the historic grain industry in Buffalo. Numerous of O’Callahan’s drawings and prints focus on grain elevators and operations. Also included in the exhibit is a terrific vintage aerial-view photo showing the Buffalo River, Ship Canal, Ganson Street.

The Harold L. Cohen exhibit includes generous examples of woodcuts, wood engravings, linocuts, collagraphs, drypoints, and etchings, along with inky, prepared matrix printing plates for one each of the various print technique examples. There are also a few drawings not associated with (displayed) prints.

Stylistically, the works range from abstract to figurative—typically with vaguely discernible figurative elements half-hidden within, emerging from, what at first glance looks like abstraction—and communicate artist sensibilities ranging from joy to mourning.

The three print work exhibits continue through May 27.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n14 (Week of Thursday, April 5) > Art Scene > Printmakers address globalization at UB Anderson Gallery This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue