If You've Never Wept and Want To, Have a Child

by Woody Brown

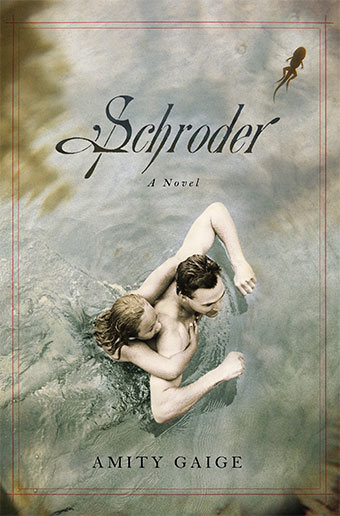

Schroder

By Amity Gaige

Twelve, February 2013

“Listen,” implores Erik Schroder, and with that the novel hurtles forth like a bullet out of a handgun. Schroder is the eponymous narrator of Amity Gaige’s third novel, a story that is ostensibly “a record of where Meadow and I have been since our disappearance.” The text is addressed to Laura, Schroder’s estranged wife and the mother of Meadow, their daughter, whom he, facing the imminent loss of his custodial rights after a plausible but extraordinary sequence of post-divorce legal wrangling, has kidnapped. The story, based on the real tale of convicted kidnapper and suspected murderer Christian Gerhartsreiter, alternates between breakneck retellings of the events of the narrative present and recollections no less immediate of the warm and stormy days of parenthood and marriage. To say that the piece of fiction Gaige has produced is successful is a serious understatement.

We learn throughout the early chapters that Erik Schroder as a boy fled split Berlin with his father Otto and, confronted with his foreigner’s necessary discomfort, constructed a new name and identity for himself: Eric Kennedy, a name he chose for its obvious association with American royalty. Schroder concedes that he “did not sufficiently debunk the rumor of himself as a second cousin twice removed to the Hyannis Port Kennedys,” but that is perhaps the least of his lies. Laura is of course not privy to any of the actual details of Schroder’s life and the story of their divorce is also the story of her gradual recognition of the mask her husband has worn for as long as she has known him.

Schroder recounts the events of the novel in the past tense, from a point in time that we can safely assume is one in which things are not going very well. Gaige’s decision to write the story this way effects a comforting and conventional form, albeit one that is strikingly inflected by the desperately self-centered narrative perspective. But more importantly, Schroder’s nostalgic perspective of his own life results in some truly stunning sentences. Olga Karman, a poet and, coincidentally, my grandmother, told me that one of the highest compliments a writer can give to another writer is to say, “I wish I had written that.” That nicely captures the deep appreciation writers have of each other’s work, an appreciation that is tied inextricably with jealousy. There are many occasions throughout Schroder that made me say that, from sentences of mind-boggling and incisive economy to paragraphs in which each word reads like its only reason for existence is to be there, at that exact point on the page, and no place else.

“And when he was in love with her,” Schroder says, speaking of himself in the third person, “a minute no longer seemed like the means to an hour. Rather, each minute was an end in itself, a stillness with vague circularity, a gently suggested territory in which to be alive.” What can a reader do with a line like that? Underline it? Paste it to his forehead and spend the rest of his days a silent proselyte? The voice Gaige gives Schroder to tell his story blends with his earnest, febrile desperation to create a resonant, harmonious chord. Consider the following, in which Gaige melds seamlessly his simultaneous urges to reassure himself and excuse his actions, to justify his decisions and to come to terms with his overpowering love for his daughter:

But tell me, isn’t that what childhood is? An involuntary adventure? A kidnapping? Before birth, before your specific appearance, what angel asked you, in the astral light of the anteworld, Excuse me, little presence, would you like to be born now?

“Little presence.” It is regarding Schroder’s daughter, Meadow, and his life spent as a father to her that Gaige is certainly at her strongest. When I reviewed Molly Ringwald’s collection of stories last year I said I was impressed with how frankly she discussed the uncomfortable things children and their parents do, the scandalous weirdnesses that seem inadmissible in normal conversation. I now feel stupid for having said that. Gaige describes with truly impressive skill the ineffability of love like no other. All of it—the pathos, the beauty, the reverberations of affection that can shake tears from your eyes and the coincident feelings of apathy or even disgust; in short, both sides of the ambivalent parental coin—all of it is there in Schroder. Upon arriving at Lake George, Schroder watches Meadow swim: “In the near distance, Meadow was indeed swimming, her head held stiffly just above the water, a big grin on her face. Just then the sun reemerged from the sky’s lone cloud, spilling outrageous light across the surface of the lake, which now seemed to be filled with boiling gold.” The word “outrageous” in that context might be lightly termed inspired. But the beauty of that passage cannot be completely spelled out, just as Schroder himself cannot come to terms with the tides inside his own heart: “Some things you can’t explain, you just can’t, no matter how sympathetic nor how moving in her own right is the listener.”

Schroder is refreshingly bereft of the formal wizardry that characterizes much of the postmodern fiction that attracted academic interest in the second half of the twentieth century. This is good and this is nice. Instead, Gaige turns to the ineluctable parts of life that go by big-sounding names: love and fear, for instance. We are reminded here of the words of William Faulkner in his 1949 Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “The young man or woman writing today has forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.” Gaige, like Michael Chabon and Jonathan Franzen and Jennifer Egan, has certainly not forgotten the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself. Schroder is an impassioned defense of the tragedy and beauty of the split subject.

Not to mention the fact that this book is great fun to read. It is relentlessly compelling in the way that mystery stories can sometimes be. This is partly because Schroder is told like a defense to a jury from the first page: “So it’s hard not to also think of this as a sort of plea, not just for your mercy, but also for that of a theoretical jury, should we go to trial.” This grants the novel an insistent immediacy reminiscent of many great Russian short stories, in which form of the impassioned defense is employed time and time again. I read it in two days of intermittent reading, during which I underlined a lot and cried once. You should certainly read it as well. You may find yourself thinking afterward, as I have, the same words Schroder addresses to his wife: “I’m grateful really, and also sad, that you were so beautiful.”

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n10 (Week of Thursday, March 7) > If You've Never Wept and Want To, Have a Child This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue