A Shot in the Dark

by Mason Winfield

June 6, 1813: The Battle of Stoney Creek, Thorold, Ontario

It was early June, 1813. For the first time in the war, the Americans had naval support on Lake Ontario and a land force on the Niagara capable enough to attack someone. Their capture of Fort George in Newark (today’s Niagara-on-the-Lake) was a gut-punch to the British in Ontario. They missed scoring the complete knockout when the fort’s former commander, Brigadier General John Vincent, and his redcoats were on the run, but Vincent was still on the ropes.

Things were so bad that Vincent had sent his Canadian militias home, abandoned all his Niagara outposts, and pulled his 1,600 redcoats together, chiefly members of the doughty Eighth (“the Leather Hats”) and Isaac Brock’s storied 49th regiment (“the Green Tigers”). After hoofing it for a week, Hats, Tigers, and Vincent landed in a fortified camp on the edge of Lake Ontario at Burlington Heights, a 330-foot-high ridge in Hamilton. The US closed in with double the numbers and set up in camps by Stoney Creek near Thorold.

Though he may not have showed it at Fort George, Vincent was a scrapper, and in no mood to let history happen without him. He sent Lieutenant Colonel John Harvey to scout out a sucker-punch. Harvey found serious flaws in the American camps. They were too spread out. Their watchmen weren’t watchful, and backup units were a long way off. Harvey recommended knifing them as they slept: a night attack.

Here’s where the legendary Billy Green comes in, Canada’s male Paul Revere. (We’ll meet the female version, Laura Secord, later this summer.) Green’s brother in law Isaac Corman got caught rubber-necking as the Yanks were torching Fort George. Duh. When it was discovered that Corman was no combatant but a cousin of General William Henry Harrison (a future US president), he was released and even given the password to get through the American lines, so long as he promised not to tell the British. (Double duh, this time the other way.) He kept his promise. He told someone else who told the British: 19-year-old “Billy the Scout.”

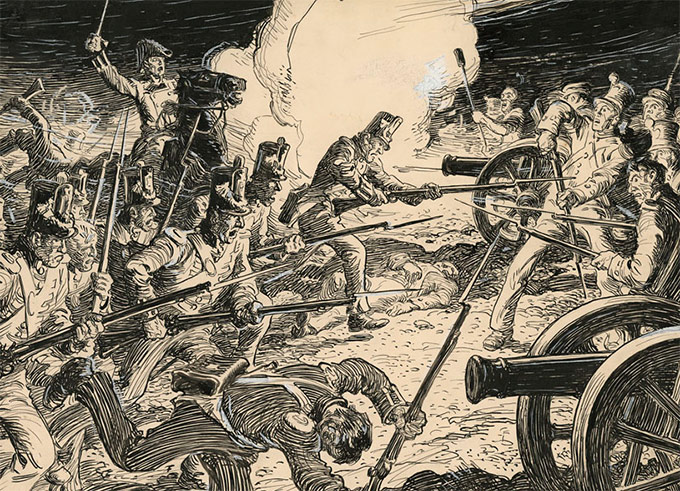

Seven hundred stealthy redcoats left Burlington Heights at 11:30pm on June 5. They overwhelmed a small US picket (scout) post with the bayonet and crept closer. That password made it easy. Some Canadian homers like to suggest that Green himself knifed a sentry, but the British officers’ reports make no mention of it. Still, the original plan to stick sleeping Yanks was on course. Then a Mohawk dropped a sentry with an arrow and finished him with the tomahawk, and some British officers couldn’t hold back the woofing. Bye bye, surprise pajama-knife-party. Still, the Americans were so spread out that half the army never knew what was up until their own cannon lit up the night.

The Americans woke, formed lines, and held against a number of bayonet charges. (You didn’t expect this out of them until later in the war!) British losses were heavy. But around 2am, US General William Winder made a big mistake. He sent the Fifth Infantry to reinforce the left flank, giving away his unarmed cannon teams and opening the front door to his formation. (Might as well put up a “Free Beer” sign.) The whole British force charged in. As with Clinton-era Arkansas basketball, “40-minutes of hell” ensued.

While 3,400 US soldiers were in the region, this 700-man night attack had probably engaged a scattered 1,200. For most of the night, the Americans had no idea how many foes they had or even where they were. The two top Americans, Generals Winder and Chandler, charged into the dark and became quick POWs. Command fell to Colonel James Burn, but it took awhile for him to find out, which was probably good. Burn’s first move was to attack his own 16th Infantry, lost in the dark without leaders. As for the British, they had entered the obscurity with some sort of plan, but their commander, John Vincent, fell from his horse, conked his bean, and was found bewildered (minus horse, hat, and sword), seven miles away.

Thoroughly spooked, the Americans got more bad news. The British had attacked the American naval base at Sackett’s Harbor, and the warships that had supplied this land operation headed back to defend it. The Americans fell back to Fort George. British, Canadian, and First Nations paramilitaries cheerfully followed, a season of guerilla warfare ahead.

Though the British had captured the two highest-ranking Americans, they had lost more men, and enough (200) to figure as a loss in most circumstances. Still, the Battle of Stoney Creek was a major counterstroke. Stoney Creek was as far as an American force would ever march into Canada, and, except for it, the theater of this whole clash in the central Great Lakes was a one-mile deep band along the Niagara—to the west side of which the War of 1812 had finally, earnestly come.

Mason Winfield is the author of 10 books, including Ghosts of 1812 (Western New York Wares, 2009), a history of the 1812 war on the Niagara.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n23 (Summer Guide, week of Thursday, June 6) > A Shot in the Dark This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue