Albright-Knox Art Gallery Showcases its Pop Art Collection

by Jack Foran

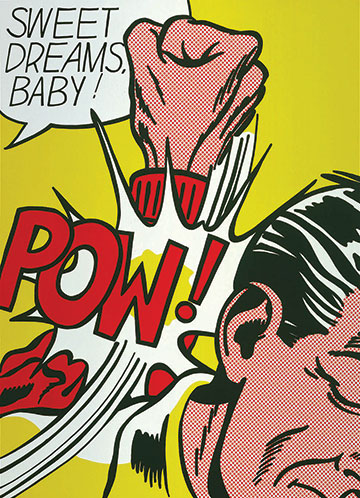

Sweet Dreams, Baby

Sweet Dreams, Baby, the Pop Art and its predecessors show currently at the Albright-Knox comprises some of the really fun stuff.

Claes Oldenberg’s soft sculpture map of the Borough of Manhattan as a side of beef, and two of his plaster of Paris (in)edibles, cake and ice cream.

Roy Lichtenstein’s comic book stills with figures in black outlines and solid color areas and Ben Day dots, and verbal content in dialogue or monologue balloons, and extra-pictorial descriptions in onomatopoeic terminology of the illustrated dynamic action. POW! And Lichtenstein’s elegant painting/sculptural piece in dual homage to Matisse and to Picasso as founder and chief preceptor of the cubist school, entitled Picture and Pitcher.

Marisol’s wood and mixed media sculpture of generals George Washington and Simon Bolivar on a barrel horse playing a lively martial tune out of its anus. A curator’s note explains the origin of the musical component of the piece and why it hasn’t been used with the exhibited work for the last couple of decades. But you can hear it now.

And lots of Andy Warhol, the centerpiece artist of the exhibit. Including 100 Campbell’s Beef Noodle Soup cans, the Marilyn silkscreen in garish all wrong colors (a kind of fauves reminiscence), multiples of Jackie just before and after the assassination, and two sets of similar but varicolored multiples, of Chinese Republic former Chairman Mao, and of Albright-Knox Art Gallery former Chairman Seymour Knox, Jr.

Fun stuff, but raising or underscoring lots of serious art questions. Like why is some art worth millions, and other art—that looks, as far as just about anybody can tell, exactly like the art that’s worth millions—worth little or nothing? A question tangential if not fundamental to a passel of current court cases about Andy Warhol’s art.

The fundamental question may be about skullduggery related to the authentication process, the determination of what work is actually by Warhol and what isn’t. As well as what that means, actually by Warhol. But skullduggery facilitated by the kind of industrial mass production artmaking methods he employed.

Pop was the first art ever taking on industrial mass production objects as subject matter, and employing industrial mass production artmaking. The multiples thing was a large part of the message. But mass production can get out of control. (A little like Big Anthony and the pasta pot. That was actual magic, of course, but the result was much the same. More pasta—or art—than whoever it was bargained for.)

And which broaches the question—even if this is not the legal question—why what could be called exact reproduction artworks—particularly for anyone unable to tell the difference between the exact reproduction and the original, which is to say, just about everyone—are so undervalued, in every sense, in comparison with originals. Forget about the fact that the Michelangelo David in Delaware Park is bronze and the original is marble, why do people go to Florence, Italy, and pay an entry fee for the privilege of gazing in awe for a few minutes or half hour at the original—some of the same people, I would venture to think, who drive or bike or stroll past the exact reproduction statue here, probably without a glance at the work or moment’s thought about it?

Predecessors to Pop Art that eased the transition from Abstract Expressionism’s ukase against depiction of recognizable objects included the relatively little known British Independent Group, represented here by works of artists Richard Hamilton, John McHale, and Scotsman Eduardo Paolozzi. An explanatory note says the members of this loosely affiliated group “aimed to raise the status of popular objects and icons within modern visual culture,” and though without a true common aesthetic, they shared an aesthetic principle—in reaction, in the postwar period, to wartime rationing—that they referred to as “the aesthetics of plenty.”

American Pop Art went a step further in its attention to, attraction to, mass production consumer goods and associated creature comforts and lifestyles, sometimes by way of satirizing, sometimes by way of wallowing.

Additionally, the new focus on objects—objective reality—opened the door to new focus on social and political reality, in the era of the civil rights battles and Vietnam War protests. To social reality artists of various stripes and persuasions, from Keith Haring to Kara Walker, Barbara Kruger, and Cindy Sherman.

Pop Art is sometimes credited with initiating and fully participating in the social reality project, but the claim is overstated. The Pop Art focus on materiality pure and simple—the fascination with glitz and glamour—precluded any serious development in the social reality direction. The exhibit features a single Warhol tentative social reality piece—an appropriation work, based on somebody else’s photo—of a police and police dog attack on a black man during the civil rights street wars. Whereas, the Mao multiples are about the Chinese leader as culture hero, national icon, no sense of the man as murderer of millions.

Also listed among the predecessors are Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, who were to Pop Art as Cezanne was to Modernism.

No Brillo boxes in this show, but an SOS pads box, in Tom Wesslmann’s kitchen sink and cabinet sculptural work with Mondrian reproduction décor item.

The Pop Art show continues through September 8.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v12n28 (Week of Thursday, July 11) > Art Scene > Albright-Knox Art Gallery Showcases its Pop Art Collection This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue