The Gospel According to Shaver

by Buck Quigley

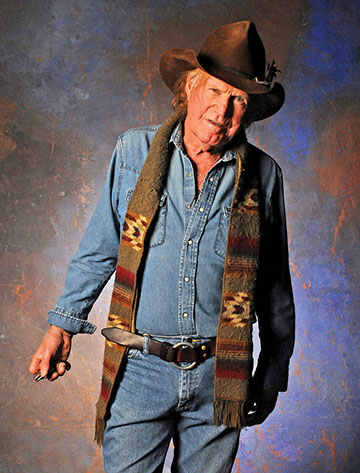

Legendary singer-songwriter Billy Joe Shaver brings his message to Sportsmen’s Tavern

“Willie’s a good old boy—that’s for sure,” says legendary songwriter Billy Joe Shaver of his longtime friend Willie Nelson. “You know, I met him in 1953. I was just a kid, really. It was a long time ago.”

Shaver took the time to talk to Artvoice while he and his band stopped for gas along the Interstate in Tennessee near the Kentucky line, in between gigs. He would have been 13 at the time of this initial encounter. Nelson would have been 20. He remembers the circumstances of that first meeting:

“Oh yeah. I knew an old boy named Johnny Ellis—that was his radio name. I was out hitchhiking is what it was, aiming for Dallas. And he [Ellis] drove by with Willie and recognized me and stopped. So I met him, and I remember he wrote on a little pack of matches: Good luck with your songs in Nashville. I had no idea what it meant. And sure enough I wound up in Nashville—I don’t know.”

There are many episodes in Billy Joe Shaver’s life that suggest the hand of fate. He writes in his autobiography Honky Tonk Hero (University of Texas Press) about how his father Buddy Shaver tried to kill him two months before he was even born. Convinced his wife, Tincie, had cheated on him, he took her out into the sweltering heat of June outside of Corsicana, Texas—near a remote stock tank. There, in a drunken rage, he beat her within an inch of her life, stomping her mercilessly with his cowboy boots and leaving her, and the baby growing inside her, for dead.

Hours later, an old Mexican ranch hand discovered her there when he came to water his cattle. Though he knew the Shaver family he didn’t recognize her at first through all the bruises and blood. When he did, he put her over his horse and carried her home. She lived, and even more miraculously gave birth to Billy Joe on August 16, 1939.

Billy Joe Shaver

Tuesday, July 8 at 8pm

Sportsmen's Tavern

326 Amherst Street. Tickets $30 advance / $35 at the door

Her marriage was over, and a month after giving birth Tincie took a job working in a honky tonk called Green Gables an hour and a half to the south, outside of Waco. She was recruited for the job straight out of the cotton field she was working with her newborn son strapped to her back and his two-year-old sister Patricia dragging along behind on a gunny sack filling with cotton. While his sister spent her childhood being passed around among various aunts and uncles in town, his maternal grandmother raised him until the age of 12—the age at which he began raising Hell. He and his sister then rejoined their mother in Waco.

There, Shaver proceeded to get in fights and struggle with school. He clashed with his stepfather—who gave away the young boy’s guitar as payment to a Mexican family for yard work. When he was in seventh grade, a 12th grade English literature teacher recognized in him an innate talent for writing. He still credits that early encouragement with giving him the confidence to write songs, although he ultimately dropped out of school and embarked on a checkered Naval career at the age of 16. That stint ended with an honorable discharge thanks to a top-notch Marine lawyer after Shaver was charged with resisting arrest, destruction of government property, and assaulting an officer at a party.

Out of the Navy and back in Waco, he met his wife Brenda at a high school football game. They quickly married and had a son. He worked a side job breaking horses for his new father-in-law and riding in rodeos. Then, while Shaver was working at a local sawmill, his hand became caught under a pressure chain that fed enormous oak doors toward large steel wheels edged with whirring razors. There were sparks and blood. He picked up two of his severed digits from a pile of sawdust and went to the hospital, but it was no use. The doctor was able to sew him up, but he lost most of the first two fingers on his right hand, and the tip of the third.

Of course, there were complications. His entire arm became infected and so badly swollen that it looked like it would need to be amputated. Shaver would not allow it. He prayed to God that if He would let him keep his arm, he would get to work strumming his guitar with his remaining fingers and writing songs. Eventually, the swelling went down.

He then spent many years bouncing back and forth between Nashville and Texas—through separations, infidelities and divorces—working for $50/week as a staff writer and trying to get a big break. It didn’t come until seven years later in 1973, when Waylon Jennings released his historic Honky Tonk Heroes album—a collection of songs Shaver wrote—which is generally hailed as the start of the Outlaw Country movement. It signaled a move away from the slick “countrypolitan” sound that had increasingly come to typify the country music of the time. The sound was more rugged, and the songs more real. It sold millions, and made country music a relevant genre again.

“I just went ahead and wrote,” Shaver recalls, “Waylon told me, after we done that album, he said ‘If I ever catch you writing to try to get one of them awards, I’m gonna shoot you right between the eyes.’ [laughs] “Cause he was all against that kinda shit. ‘Don’t worry about that,’ I said, ‘I ain’t gonna do that.’”

Jennings was initially hesitant to make the record. Shaver famously confronted him and threatened to kick his ass “in front of God and everybody” if he wouldn’t at least sit down and listen to the songs. Jennings did, and was floored by what he heard.

“Once everything took hold, he was alright with it. He needed them songs as much as I needed him to sing ‘em,” Shaver says. “’Cause the songs are so much bigger than me, and I couldn’t possibly sing ‘em as good as he could. It put me on the map, man.

“Kris (Kristofferson) recorded one even before that—‘Christian Soldier’ on that Silver Tongued Devil album. It helped me quite a bit. Kris has been a good friend. He’s such a genius, really.”

While many of his best-known songs tell stories of fast living and partying (Georgia on a Fast Train,” “Honky Tonk Heroes”), there is also a strong Christian element in much of his work (“If You Don’t Love Jesus, Go to Hell,” “I’m Just an Old Chunk of Coal”). At 74, Shaver’s live performances continue to be sweaty and energetic, often turning into something resembling a sort of secular revival.

“Yeah, nobody complains,” he says, “It’s just…I’m a born-again Christian. It happened to me. That old guy died and the new one lives—even though I still slide back now and again.”

Did this transformation happen in a church? Speaking from the truck stop, Shaver explains it like this:

“No, no. I went up on this mountain there outside of Nashville at a place called the Narrows of the Harpeth. The river goes around a bend there and it comes up this big, tall cliff-like thing and there’s a hole underneath the cliff that was chiseled by slaves. You can see the chisel marks. And so they’d chiseled it so the water would run over into this man’s plantation. And you can go in there. It’s pretty tall—you can stand up in places. So the guy got him some free water there.

“Up at the top of the thing—there’s kind of a treacherous trail. My son showed it to me. He used to go around spelunking. But up there at the edge of the cliff there’s this big altar-like thing. Rain or wind or something has hewn that thing out, and it’s like a mushroom. Just like a big altar.

“Well, I’d come in late one night doping—doing everything in the world—I was near death. I was just about to die. And I saw this vision when I opened my door. It was about four in the morning and everybody was asleep. I opened the door to my bedroom and it was all real white—somethin’ like neon, but a little bit more. And I saw Jesus Christ sitting on the edge of my bed, at the foot of it. His eyes were like coals. I decided I didn’t want to look at him no more. But he had his hand to his head, and I heard his inaudible voice asking: How long are you gonna do this?

“I turned around and left, got in my pickup truck and went out to that place that seemed like a sacred place to me—where that altar was. It was a cloudy night, no stars out. It was dark as pitch. And how I got up that trail I don’t know. But I got up there and I coulda swore I jumped off that cliff ‘cause I was just so sick of myself. I’d just done everything wrong.

“I found myself on my knees, though, and my boots were off with the cliff at my back. And I’m at that altar, and I just asked God to forgive me. That’s all I wanted. Just for Him to forgive me. It would take me forever to tell you all about that, but I came down that trail, and I was singing ‘Old Chunk of Coal.’ It just came to me, and I got the first half written coming down that trail.”

“I went and got my family, and the very next day we got two U-Haul trucks and loaded them up. Boy, they were mad as Hell at me. ‘Cause I pulled my boy out of school, and my wife had friends there. And they were all mad at me anyway because I wouldn’t quit what I was doin’. And I made ‘em get with me and go on down to Houston and we got a place down there. I knew that in Houston, I wouldn’t be able to drive—‘cause it’s hard to drive there even if you’re sober.

“I went cold turkey, and quit everything. Drinkin’, drugs, smokin’—I was chain-smoking cigarettes. I was never much of a pot smoker because I always liked something goin’ up, you know? And I could walk down to this little store there and get Melba toast. I could keep that down. And A&W diet root beer—I could keep that down. But that’s all I could keep down. And this went on for several months. I dropped down to 150 pounds. I was skinny as a rail. Finally, one night I wrote this song called ‘I’m In Love.’ It’s about being in love with Jesus Christ. It’s a spiritual song—most people think it’s a love song but it’s not. Or, it’s a different sort of love song. That’s the song that saved me. I finished it, and asked my wife to cook me up some eggs. She did and I was able to keep ‘em down. And that’s when I started coming back.”

As his health returned in Houston, he got a phone call from an old friend, Willie Nelson. Soon, he was on the road again, opening shows for Nelson and Emmylou Harris—with a small band featuring his 13-year-old guitar prodigy son Eddy Shaver backing him up. Allman Brothers guitarist Dickey Betts had tutored him as a boy. When the school principal was approached to see if it would be possible for Eddy to miss school for the dates, the principal said he would make a deal: “If you’ll promise not to bring him back, I’ll let you take him.” Eddy was a Hell-raiser like his Dad, but he sure could play.

With his confidence returning, the Shavers moved back to Nashville. Billy Joe was releasing albums again and touring with his son— regaining the respect he had earned twenty years earlier as a songwriter’s songwriter. Actor Robert Duvall, a fan of Shaver’s, gave him a role in his film The Apostle. Things were on the upswing.

Then, as so often has happened in his life, tragedy and heartbreak came calling. Brenda, his first wife, whom he’d married three times, was diagnosed with an advanced form of cancer. He drove her back and forth between Waco and Austin for aggressive chemotherapy treatments, causing the tall Texas beauty to loose her hair and strength. While Shaver was in New York for a few engagements, she began throwing up blood. He rushed back to the hospital in Austin where a doctor informed him that her organs were shutting down. He sat with her a few days before she died on July 30, 1999.

Cruelly, one year later, on New Year’s Eve, his son Eddy died of a heroin overdose at the age of 38. Shaver’s mother, Tincie, passed away the same year.

Then, in 2007, outside of Papa Joe’s Saloon in Lorena, TX, Shaver found himself in a confrontation with a man wielding a knife. He shot the man in the face with a .22 caliber handgun. The man suffered non-life threatening injuries, and a jury found him not guilty of aggravated assault in the incident—believing he had been intimidated by the younger man.

Does life imitate art, or is it the other way around? Like the characters in his songs, Shaver’s life has been a mixture of joy, sorrow, happiness and pain. Through it all, the search for redemption remains constant. It’s a theme that runs through his new album Long in the Tooth (Lightning Rod Records), his first release in six years. The 10 song collection features a mix of styles that hearken back to his early successes with Waylon Jennings as well as the hard rock / country brew he cooked up with his son Eddy. His new lyrics and melodies are as rough-hewn and beautiful as anything he’s ever recorded. A standout is “I’m in Love,” the spiritual that signaled his recovery from addiction. The lead track, “Hard to Be an Outlaw” is a duet with his friend of over 60 years, Willie Nelson.

In support of this release, Shaver and his band are in the midst of a 40-city summer tour. What can fans expect from his upcoming show in Buffalo?

“We’ll just give it everything we’ve got. We’re happy to get there and happy to share what we’ve got with them. And they share a lot with me, so I get as much as I give. I enjoy this. I enjoy entertaining and singing. Each song is like a little capsule of time, and it takes me back. It’s a wonderful way to live. We packed ‘em in last night in Nashville at a place called 3rd and Lindsley. It was a full house and you couldn’t hardly move. We put on a great show and everything came off great. We made over our quota—did well in the money part—and sold $2,000 in merchandise. So I’m happy living life right now.”

Billy Joe Shaver brings his honky tonk revival to the Sportsmen’s Tavern on Tuesday (7/8) at 8pm. $30 advance / $35 door.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n27 (Week of Thursday, July 3) > The Gospel According to Shaver This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue