Birds and Their Songs at BT&C Gallery

by Jack Foran

Avian Music

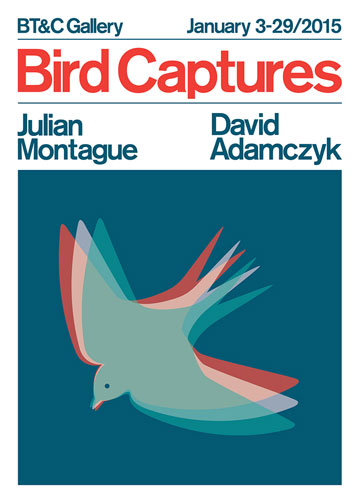

Two artists joined forces Saturday night at the BT&C Gallery in a visual and audio presentation about birds. Augmented further performances are scheduled for January 13 and 29 at the same locale.

The artists are Julian Montague, showing some 100 bird photos he has taken over the past ten years, and musician and composer David Adamczyk, playing bird songs he has painstaking contrived to reproduce on his somewhat altered for the purposes violin and electronics.

There are two basic ways of observing and photographing birds. What might be called the National Geographic way, involving elaborate and expensive equipment and logistics. Somehow have the photographer camp out right in the eagle’s nest. The results often breathtaking. Or at least what National Geographic shows of the results. The other way what might be called the regular people way. The way we all—everyone except the National Geographic photographer—observe birds and photograph them if we try. The results often disappointing. Bird subjects far away and tiny, sometimes lost in surrounding trees and greenery. But if we work at it—the observation and the photography—we get better at it. And maybe more important, occasionally lucky.

Montague’s way is the regular people way. And illustrates the trial and error process (what National Geographic edits out). Each photo—made without telephoto lens or other special equipment—is labeled as to bird species and sequence number of photos of that species: “attempt (number) of (number).” Lower numbers—indicating earlier attempts—in a given species sequence are sometimes not so great. Birds hard to see against backgrounds or foregrounds. Or too far away to distinguish. Tiny specks in the sky or on a tree branch. The Cooper’s Hawk, attempt 4 of 7, on a branch more or less directly above the photographer, so you can’t really see the bird’s head. Or the Common Loon, attempt 3 of 5, way on the other side of some pond. Pretty much the frustrating way one usually observes a loon. In a minute it’ll dive and disappear and turn up somewhere else on the water, but as far away or farther. Or Eastern Phoebe, attempt 1 of 7, or Baltimore Oriole, attempt 3 of 7. Both pretty far away from the camera, the oriole a little hard to find in the picture even.

The higher numbers—nearer the end of a species sequence—usually much more successful. Some really superb. The Barred Owl, attempt 25 of 25, perched on a branch, looking backwards over its shoulder, straight into the camera. Or the Roseate Spoonbill/Little Blue Heron, attempt 3 of 3. Spectacular. Perfect mix of sun and shadow lighting, swamp scene like a stage set, magnificent bird, awesome aerial takeoff. Likewise the Great Blue Heron, attempt 4 of 4. Against a dark blue water background. Blue on blue.

All against Adamczyk’s bird sounds. How he produces these, basically, first he finds bird song recordings—the Cornell University Ornithology Lab is a good source—and listens over and over, but also uses computer programs to translate the sound into graphs representing pitch and duration and dynamics, then translates the graphic data into more or less traditional musical notation, on a staff. What he comes up with at this point are a number of discrete musical phrases or themes. He cuts these—the phrases or themes in traditional notation—into separate bits and pieces and pastes them—lots of white space all around—on a large sheet of paper. Then draws a road map connecting the bits and pieces such as the bird would connect them, and plays them on the violin.

The prepared violin features strings on strings—actually horsehairs, like the hairs on an ordinary string instrument bow, and rosined like bow strings, and tied to one of the regular violin strings, various locations along the regular string length for different sound effects, including the part of the string below the bridge, between the bridge and the violin tailpiece—that he plays by grasping the additional string between thumb and forefinger and pulling, sliding thumb and forefinger along the string, producing sounds, from stuttery staccato to liquid glide. (Like a bow on a string produces sounds, only different.)

The bird song project is a work in progress, Adamczyk says. Coming along remarkably though, based on Saturday’s performance. Authentic bird sounds to human ears anyway. (No birds on hand to really tell. Possibly react. That could be a future phase.)

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v14n1 (Week of Thursday, January 8) > Birds and Their Songs at BT&C Gallery This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue