Here and Gone

by Jack Foran

A retrospective of the great Hollis Frampton at CEPA and Squeaky Wheel

The Hollis Frampton exhibit on three floors of CEPA galleries extends also into Squeaky Wheel space—both organizations are now in the Market Arcade building—where two of his films are playing. Don’t miss the films. To see what avant-garde cinema—or a significant component of it—looked like in the 1960s, but also for the context one of the films supplies to the photos in the rest of the exhibit. Also because Frampton—who taught at UB in the years prior to his tragic early demise, of cancer—was such a genius. Everything he made or touched is worth seeing and contemplating.

The other film is very funny. In an avant-garde sort of way. There’s this couple, maybe in their early twenties—they live together—having an argument that may well finish off the relationship. Possibly about an unfaithfulness on his part that she has somehow found out about and he doesn’t want to talk about. But since they are talking about it, he keeps trying—futilely—to secure some moral high ground in the argument. Keeps saying something like “You don’t have to know.” We don’t know much for sure because of Frampton’s cinematic technique in this case of stuttery repetitions of minimal bits of filmed action and dialogue, parts of sentences, parts of words. A few frames over and over, then on to another few frames, maybe not strictly sequential. The film is called Critical Mass.

The context film is called (nostalgia) and is specifically about the photos—some key ones—we see through the rest of the exhibit. A dozen or so photos he made and has lived with some time and is now for some reason symbolically putting behind him. Placing them one by one on a stovetop electric burner, and as he talks about each photo, the circumstances of its making, suddenly it starts to smoke, then combusts, and gradually darkens and slowly contracts to black ash. Next picture.

The subject matter of the photos is his past life. Some of his early photographic work. And some artist friends he knew from school or the New York art scene in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Carl Andre, James Rosenquist, Frank Stella, Larry Poons. Informal portraits of them in their studios, amid studio mess. One photo he didn’t take and doesn’t know who did, but that stuck in his craw somehow. Possibly of a farmer, after a weather event destruction of his fruit crop, contemplating his loss.

But pretty straightforward stuff—it seems—compared to the bizarro experimental technique argument film. Until some little confusions occur. You think it’s you. You’re not getting something. But the match-up of photos and descriptions starts to go awry. Showing one photo but talking about another. Then in the next sequence, the one he was just talking about comes up. The last photo—wherein something is reflected in a truck window, some ambiguous image that he doesn’t notice until he develops the film and blows up the image, which he then says “fills me with such dread and loathing” that he determines never to take pictures again—he doesn’t actually show. But asks the audience, “Do you see what I see?”

Happily the combusted photos weren’t the only prints of them. You see other prints of them in the rest of the show. And related photos, like the spaghetti photo he made for James Rosenquist, who wanted to put some spaghetti into one of his paintings and needed an image to copy. Frampton explains in the film how spaghetti photos then became a series for him. Nobody consumed the spaghetti or threw it out, but it just lay on the plate where he had dumped it out of the Franco-American can, and every day for the next several weeks he photographed it as it gradually dried and hardened and was consumed by mold. One of the featured photos in the film is the spaghetti on the eighteenth day.

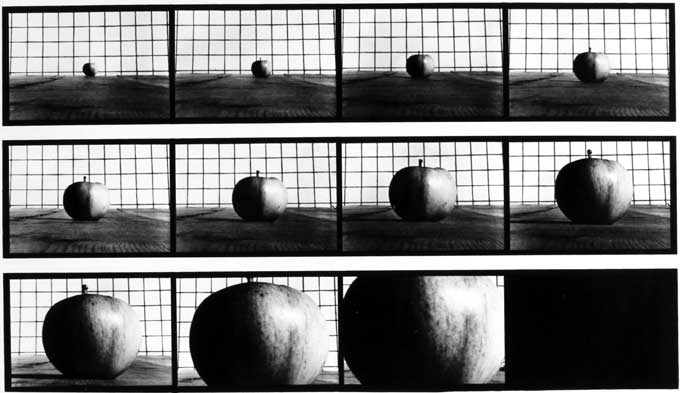

Frampton’s work was a heady mix of comic and serious. As in the Vegetable Locomotion homage to moving pictures pioneer Eadweard Muybridge, photos he made with his wife and photographer in her own right Marion Faller.

And more usually with specific reference to death and decay. As in the spaghetti series. Or the Adsumus Absumus series (Latin for “We are present, we are absent; we are here, we are gone”). Photos of formerly living things, some animal, some vegetable, preserved through desiccation somehow, together with the artist’s prose descriptions and digressions on each item. Items ranging from a dried rose—possibly from his father’s funeral flowers—to various dried exotic fish species, a toad, a frog, a much-mangled roadkill rat.

Don’t miss the prose descriptions/digressions either. They are exquisite. On an edible jellyfish portion purchased at an Asian grocery store in Syracuse, NY, he writes, in part: “In appearance and first texture, this food resembles classic India rubber bands, but it retrieves for the palate something of the childish adventure of jumping on beached bell jellies after a hard sea storm. Ever so momentarily, they resist, and then, suddenly, pressed, liquefy and vanish, leaving behind an everlasting sensation.”

The Hollis Frampton exhibit continues through September 5.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v14n29 (Week of Thursday, July 23) > Here and Gone This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue