Psychedelic Santa

by Buck Quigley

Christmas, as we all know, is the day Christians celebrate the birth of their savior, Jesus. The story of his birth in a manger, attended by the three Magi bearing gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh, is the humble tableau most of the faithful picture when they think of this sacred event. It’s a solemn scene that’s observed by 2.1 billion people, or one third of the world’s population.

But the individual most Americans associate with the Christmas season is Santa Claus. In the US alone, Christmas spending is likely to be in the neighborhood of $150 billion this year. That kind of outlay is not inspired by a poor infant wrapped in swaddling clothes, but by a big, jolly man in a red and white suit who lives at the North Pole and travels the globe in a sleigh loaded with toys, pulled through the night sky by tiny, magical reindeer.

Tradition tells us that he is based on a real person. He’s Bishop Nicholas of Myra—which is located in present-day Turkey. The poor knew this Saint Nicholas for his generous gifts. Notably, he is said to have given three golden balls to a man who, lacking a dowry, was about to send his three daughters off to a brothel. The three balls later became the symbol of pawnbrokers, and the orb a common shape for Christmas tree ornaments. St Nicholas came to be revered by many as the patron saint of sailors, children and prostitutes. In 1087 AD, his relics were transported to Bari, Italy, where a basilica was built to house his remains.

But how, then, did his legend make the move from Turkey and Italy to the frigid world above the Arctic Circle?

Many people see this as another case of Christendom absorbing the pagan rituals of foreign lands as the religion spread. Pre-Christian Germanic folklore celebrated the god Odin’s celestial hunting party made up of other gods and deceased warriors. At the end of the year, good children left carrots and straw in their shoes for Odin’s flying horse to eat during the hunt. In the morning, they found their offerings were replaced with candy. These are the roots of the story that came to America with Dutch, German and Scandinavian settlers. In Holland, Saint Nicholas is known as Sinterklaas. Santa Claus is an American mispronunciation of the word.

Still, it doesn’t explain the reindeer, or the residence at the North Pole. For that, some people point to Scandinavia and Siberia. Specifically, many contend that the Sami people of Lapland in the far north of present-day Finland, and the Koryak people of Siberia, best represent the prototypical Santa. The traditional dress of these people closely resembles the garb worn by Santa and his elves as depicted in literature like “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (“He dressed all in fur from his head to his foot/And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot”) and illustrations that predate the American Civil War. By 1885, a printer in Boston offered a Christmas card that pictured Santa in his red and white furs.

It’s often argued that the red and white costume worn by St. Nick was really just a marketing ploy developed by the Coca Cola Company, who began using Santa as a pitchman for their product. Indeed, in the 1930s, illustrator Haddon Sundblom created a series of ads featuring Santa giving bottles of Coke as presents and enjoying the product himself. Winter was always a hard time to sell soft drinks—even Coke, which was originally marketed as a medicine and continued to contain traces of cocaine up until 1929. The image worked nicely since red and white are the colors of the brand, but it’s inaccurate to accuse Coke of imposing the color scheme on Santa. The red and white suit was already accepted long before, and according to some researchers, it signifies something surprisingly different from cola.

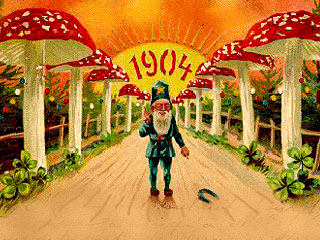

These researchers note a recurring image in many early illustrations of Santa, and point out similar images in illustrations from fantastical children’s literature, whenever magical beings like elves and faeries are on the scene. They point to the red and white spotted representations of the amanita muscaria mushroom, also known as “fly agaric” because it was traditionally used as an insecticide by floating pieces of it in milk and waiting for flies to come. The fungus was fatal to the insects, and extracts of the fungus were later used in the production of flypaper.

Flourishing in boreal regions, this mushroom commonly appears under trees in the far north, and was highly prized by these Arctic tribes. An underlying facet of their belief system was the idea of Yggadrasill, the “world tree,” whose trunk was aligned with the North Star and whose branches and roots stretched out into various planes of existence, from the underworld to heaven. They saw the large, conspicuous mushrooms as the fruit of the trees, which were often evergreens like the Christmas trees we decorate today. It is also a preferred food of reindeer, and when properly dried, the mushroom is eaten by the tribal shaman as an aid to attaining a trance state—along with drumming and chanting for hours on end.

The psychedelic properties of muscimol remain intact in the shaman’s urine, and it was common practice for lesser members of the tribe to collect it and drink it. Reindeer were also fond of eating the yellow snow left by the shaman. Some students of linguistics argue that this is the origin of the slang “to get pissed” as it applies to becoming drunk. It has also been contended as far back as 1784 that Vikings used the mushrooms to drive themselves, literally, berserk.

Muscimol, the hallucinogenic component in dried amanita muscaria, is said to have provoked hallucinations of flight among the shamans, as they perceived their reindeer sailing high above the world pulling the shamans’ sleds. Spatial perception is also affected, explaining tiny reindeer capable of covering vast distances as they sought guidance from the gods and the dead. Early visitors heard the stories told by these holy men and observed them entering the local reindeer-skin huts—called yurts—through a single hole located on the roof of the structure designed to let smoke out, like a chimney, as they visited various members of the tribe. Later, the mushroom would appear in Hungarian Christmas cards depicting a chimney sweep carrying a basket loaded with fly agaric.

Unlike psilocybin mushrooms, a controlled substance used recreationally in many countries, the fly agaric is currently not a controlled drug according to the UN. It is, however, considered poisonous and can be fatal. The ibotenic acid found in fresh specimens is a strong neurotoxin that can cause brain lesions. Some of the likely side effects of an unintentional overdose include vomiting, diarrhea, convulsions, respiratory arrest and coma, before death. Kidney damage is also likely, and probably why it was often literally filtered through a shaman—who presumably knew what he was doing.

Another drawback is the tendency toward amnesia when subjects try to recall their actions under the influence of the drug. Here, too, one can see interesting parallels between our Nordic ancestors and berserk American shoppers—who often appear to be in an ecstatic trance in the days leading up to Christmas. Many of these revelers have no recollection of their actions until many months later, when their credit card bills arrive.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n46: Holiday Gift Guide (11/15/07) > Holiday Gift Guide > Psychedelic Santa This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue