Of Mice and Men Roars

by Anthony Chase

John Steinbeck is the beloved Great Depression era novelist whose vivid depictions of struggling Americans in the 1930s lent nobility to their economic plight. Such sweeping stories as The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden, heavy with symbolism and melodramatic situations, earned him a Nobel Prize and guaranteed him a spot on high school reading lists in perpetuity. Even his obituaries, however, had to concede that Steinbeck was no Faulkner.

Still, he was among the most widely read American authors of the 20th century, and despite their debatable quality, any work by Steinbeck is dutifully dubbed a “classic.” Practically everything he wrote made the transition to Hollywood, and one novella, Of Mice and Men, even became a hit Broadway play in 1937. This “classic” tale is currently on stage at Studio Arena Theatre.

Here we meet George and Lennie, migrant ranch workers who travel together. Lennie is a big and powerful man with the mind of a child. George looks after Lennie like a big brother. Sadly, Lennie is unaware of his own strength, and has a history of killing small animals with his affection and exerting his powerful grip uncontrollably when frightened. In the play, George and Lennie arrive at a new ranch where some dicey complications await, particularly the boss’s son, Curley, who likes to pick fights with big guys, and Curley’s Wife, who is a wanton “tart.”

In both novella and play, Curley’s wife has no name. She exists to set the world of men off-balance, and it is her interaction with Lennie that seals his tragic fate.

Director Seth Gordon has done an impressive job with the unwieldy elements of this dearly loved play. Gordon is the associate artistic director of the Cleveland Play House, where this production had the benefit of three-week run before its Buffalo opening. As a happy consequence, Of Mice and Men enjoyed an energetic and confident opening at Studio Arena, with a briskly paced and remarkably secure presentation.

Harry Carnahan and Jeffrey Evan Thomas give compelling performances as George and Lennie. Carnahan emphasizes elements of the same restless insecurities associated with Lennie into his performance, reinforcing the strong bond between the two men. Thomas gives an impressively measured performance, which grows gradually through the evening leading up the climax of his meeting with Curley’s wife.

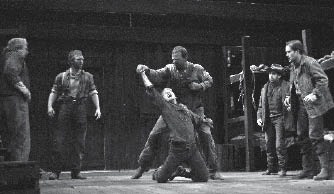

As staged by fight choreographer Guy Wagner, Lennie’s scene with Curley’s wife actually inspires a collective gasp from the audience. (Assuming you don’t know already, skip to the next paragraph if you do not want to know how this scene turns out). It is a surprising and very simple moment in which Lennie, overcome by fear, seems to push the woman away, but actually lifts her into the air with one powerful arm, snapping her neck in the process. Thomas and Amanda Rowan, as staged by Wagner, give the best performance of the famous scene that I have ever witnessed.

Miss Rowan and Vayu O’Donnell, who plays Curley, have a difficult task. Their underwritten characters seem cartoon-like by 21st-century standards. Director Gordon has elected to play into that reality and has guided the actors in the direction of farcical comedy. This pays off for them as their role in the plot turns sinister, causing a horrible irony.

Wiley Moore also has a difficult task in the role of Crooks, the resident black man. The 1937 racial dimension of the script plays uncomfortably today, but comes lashing back at us in Act Two, when Crooks has the important scene in which Steinbeck unsubtly creates the connections between all the outsiders of the play: George, Lennie, Curley’s wife and Crooks himself. It is interesting to note that the role of Crooks was originated in 1937 by Leigh Whipper, the first African-American member of Actors’ Equity Association. In the famous 1974 revival of the play, the great James Earl Jones did not play Crooks, but instead played Lennie, undercutting (or undermining) the play’s racial dynamics. Moore successfully assays the role with great wit and excellent timing, lending the man the requisite dignity and wisdom. It is worth waiting until after the intermission to see the character unfurl.

In supporting roles, Chet Carlin gives a pleasing performance as Candy, the elderly one-handed ranch hand who sees his own future when his old dog is euthanized by the unfeeling and pragmatic Carlson, played with nonchalant menace by John Woodson. David Autovino is similarly convincing as Whit, as is Rohn Thomas as the Boss.

Jeremy Holm gives an excellent performance as ranchhand Slim, bringing surprising complexity and nuance to the character. Slim emerges as the connection between the goodness of humanity and brutality of the dramatic situation, and actually facilitates the play’s climax in which George must make a brutal decision. Holms projects both great strength and great decency in equal measure in a most satisfying portrayal.

Finally, Hugh Landwehr’s complex set, gives the production a deceptively minimal tone. The California landscape looks barren and unyielding, and the movement between one location and the next is swift and unencumbered. It is a superior design.

Gordon and his company have conquered the limitations of this play and have highlighted its best qualities. Of Mice and Men, at Studio Arena, is an excellent evening of theater.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n8: The Faces of Deaccession (2/22/07) > Of Mice and Men Roars This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue