Sheldon Berlyn - Works on Paper

by J. Tim Raymond

Works on Paper @ 20th Century Finest’s Gallery in Michael Donnelly’s Interior Design

The 20th Century Finest’s Gallery inside Michael Donnelly’s Interior Design features an exhibition of the selected works of Sheldon Berlyn entitled “Works on Paper/1960s, ’70s, ’80s,” spanning three decades of Berlyn’s career as an artist. (1534 Hertel Avenue, 572-2090 / www.20thcenturyfinest.com)

After his formative years drawing and painting from direct observation, Berlyn writes, “The task I set for myself was to apply what I understood about drawing, painting and pictorial structure to abstraction.” This change followed his work being heavily influenced by the art of Hans Hoffman, Willem de Kooning, and Arshile Gorky, and it amounted to an aesthetic epiphany.

In his early work Berlyn created structures with paint, building compositions with rapid slashes and slabs, forming raw, weighted chunks drawing out depth in rigorous, carved, jutting glyphs of planes highlighted in chiarascuro in a waning, raking light. Along with his antecedents Gorky and de Kooning, Sheldon Berlyn layered smooth against raw, gouging the surface until the patent niceties of texture were macerated into a kind of tortured coherency.

Moving among the sleek confines of Donnelly’s shop, the viewer winds his way around the venue to view Berlyn’s middle period work of the 1970s, geometric abstraction. Here are the notable influences of Josef Albers and Ellsworth Kelly, works where two-dimensional space follow the color field theories of optical color. These are almost sweet, inviting one to sit down, perhaps with a magazine, safe in the knowledge that the surrounding art offers quiet if minimal security from the threat of riskier visions. These pieces do not promise deeper investigations of pictorial abstraction, and Berlyn’s stronger grounding in architectonic composition integrates hints of Cy Twombly, Jasper Johns, Franz Klein, and Robert Motherwell in the structural armatures and compositional aspects of these works.

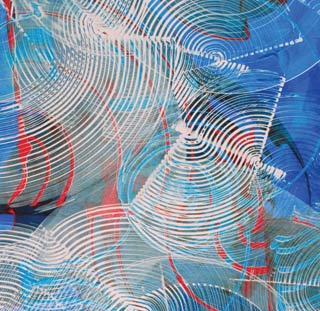

The later works of the 1980s are experiments in the “process painting style,” as Berlyn writes in his artist’s statement. He sees these as a kind of summing up of the expressionist and geometric conceptual formats seen in the earlier work. These transfer paintings are interesting curiousities of process; here they almost cry out for greater scale as lush, fluid passages create overlapping arabesques and trailing rivulets into swirling, liquid, polychrome meanders. The regimental metal framing mitigates against the dynamic acrobatics of these pieces.

I visited Sheldon Berlyn in his studio, Hawkridge, in Penn Yan, out along the Finger Lakes, up a hill on a winding road bordered by acres of grape arbors that in August must have been an intoxicating drive. In December it is all gauntly gorgeous. Berlyn and his wife, Diane, an accomplished art conservator, have lived here since moving from Buffalo seven years ago. They have had a house built to their specifications showcasing the magnificicent view of the lakefront countryside as well as Berlyn’s paintings and eclectic folk art collection. He spoke about his years at UB building the graduate painting program and the peripatetic task of finding suitable studio spaces. He spoke of the anxious pivotal period of the early 1970s during the campus riots, when Main Street was blockaded and the administration building was occupied by student protesters.

But I was especially interested in hearing about his time spent as a draftee during the Korean War. Berlyn was a company clerk in a non-combat rear area in a headquarters company overseeing the garrisoning of Korean prisoners of war. Time away from work allowed him to roam freely, sketching in the village nearby. His many drawings of Korean POWs and civilians showed a very different side of his work. These are pen-and-ink renderings on available paper—studies of old men and women in scenes of ageless toil, monks and children drawn in a fine, sure hand, bringing to life the peasants of an endlessly occupied country with vitality and a certain empathy.

These drawings, now reproduced in a color photocopied folio, give a sense of what Berlyn saw working directly from life, and connect him with an even earlier mentor, the artist Albrecht Durer. Certainly Berlyn’s service of 40 years teaching university art students basic draftsmanship and pictorial composition has kept him a fervent student himself, but perhaps they’ve kept him as well from fully evolving his own singular complexity as an artist.

In all, Berlyn remains an archetype of contemporary art culture: an artist lucky enough to gain a robust foothold in a college art department relatively soon after wartime military service. The art world is a slippery trollop of inconstancy, at once barely tethered to reality and as rapacious as a busload of tourists at a rest-stop buffet. Berlyn represents all the journeymen, lecturers, instructors, and visiting artists that make up the regional tiers of modern American art. The weight of his work lies in the conscious decisions he has made to chart his creative course through the churning swells of the art world’s sea changes.

—j. tim raymond

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n52: The Year that 2008 > Sheldon Berlyn - Works on Paper This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue