Next story: We Begin Here: Poems for Palestine and Lebanon edited by Kamal Boullata & Kathy Engel

Cathedrals of Light, Part 1: Colonel Ward Pumping Station

by Lucy Yau

Michael L. Horowitz is a New York City photographer with an insatiable curiosity who has fallen in love with the architecture of the Queen City and now considers Buffalo a playground for his work. “Buffalo is a treasure trove of intact buildings,” he says. “In New York City when a building isn’t used anymore it is torn down.”

If you’ve ever wondered what that squat round house sitting out in the middle of Lake Erie was, or what the large municipal building on the waterfront by Porter and Niagara functioned as, Horowitz’s current exhibition at the Buffalo Erie County Historical Society answers those questions. The exhibit is titled Cathedrals of Industry, and comes in two parts.

With the help of Assemblyman Sam Hoyt, Horowitz was granted rare access inside many of Buffalo’s municipal buildings. For this series, he shot the interiors of the Colonel Ward Pumping Station and the Emerald Channel Water Intake Building. “I hate closed doors. I have to know what’s inside,” says Horowitz.

His photography is an attempt to “document and preserve cultural history even as—and precisely because—it vanishes right before our eyes.”

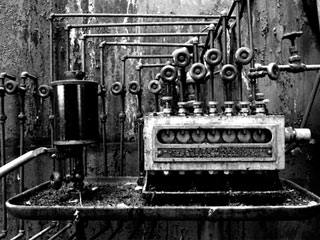

Horowitz’s large-scale, black-and-white photographs, measuring 40 by 60 inches, were captured with a Viewfinder and digital camera with a whopping 33 megapixels. He shot on overcast days to avoid “shafts of light and dark shadows.” The machines and engines are captured with a phenomenal depth of clarity and detail. They are positioned close to floor level to give the viewer the effect of being able to walk into the spaces depicted.

The building out on the water is the Emerald Channel Water Intake Building, where all of Buffalo’s water comes from. Lake Erie water collects and is filtered there before being treated and diverted to the pumping station.

The Colonel Ward Pumping Station sits on a 12-acre site at the foot of Porter Avenue and was once open to the public. Citizens were allowed in to pay their water bills, as a Department of Health “Do Not Spit on the Floor,” sign attests. The station has been closed to the outside since the Second World War, when there were fears of sabotage.

The architects of the Pumping Station were the Esenwein and Johnson Company, who also designed the Niagara Mohawk building. The station was designed on a grand scale, full of ornate touches such as terra cotta tiles, wrought iron railings and lampposts decorated with Tiffany glasswork.

When it was completed, it was the largest pumping station in the country.

Inside the pumping station, Horowitz has focused on the gargantuan steam engines constructed by the Holly Manufacturing Company. Valves, gauges, flywheels, pistons, engines, pumps and wrenches are given anthropomorphic qualities.

Between 1914 and 1917 the station’s five four-storey steam engines pumped more than 100 million gallons of water a day to the city’s industries and neighborhoods. A single engine running at capacity could pump 30 million gallons of water in a 24-hour period. The engines predated large-scale assembly lines and were essentially handbuilt.

However, despite being built to last indefinitely, their usefulness only lasted a few decades. The steam engines required huge furnaces and their voracious appetite for coal eventually made them obsolete. Today they sit silent next to smaller, more efficient electric motors.

There are currently efforts underway to revive at least one of the steam engines, with the possibility of compressed air for power.

Horowitz has captured the forgotten grandeur of the space and the sublime wonder that were these machines. These structures are symptomatic of a once glorious Buffalo. They hark back to a time when citizens took pride in civic projects. “These were temples to municipal water. Something like this would never be built today—taxpayers would think any kind of extravagance in their public works would be immoral,” says historian Cynthia Van Ness, director of Library and Archive Services at the Historical Society.

Today, functionality and utilitarian purposefulness has replaced ornamentation.

Horowitz’s series is a window onto an industrial way of life in Buffalo that has ceased to exist, when the waterfront hummed with activity. The enormous din that accompanied the activity of the steam engines was surely deafening.

For information on tours of the station, call 856-6696. Horowitz’s exhibition at the Historical Society is scheduled in two parts: Part I: Colonel Ward Pumping Station will be on view until July 25, 2008; Part II: Buffalo’s First Ward grain elevators will go on view August 8, 2008 to January 25, 2009.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v7n6: The L Word (2/7/08) > Cathedrals of Light, Part 1: Colonel Ward Pumping Station This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue