Next story: Beyond the Beyond

Authenticity

by J. Tim Raymond

Our correspondent tracks the history of a drawing attributed to Renior

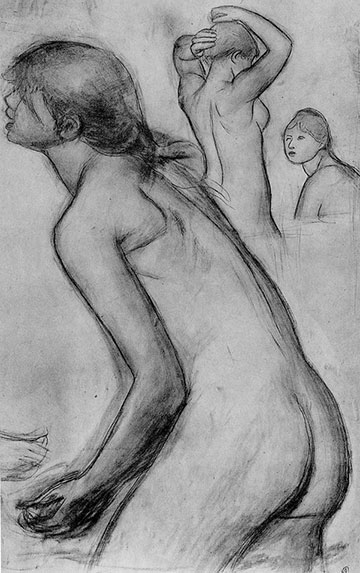

I first saw it as a jpeg in my iPhone: a pastel chalk drawing, about 20 by 30 inches, worked in a clearly professional manner, depicting two naked figures in repose, as if bathing. There are faint indications of model stands covered in cloth over pillows. There are indications of a third figure faintly modeled in the middle right foreground. The figures appear to float in a vaporous field of bluish chalk. Each pose is finely modeled with crisp outlines and closely toned in a range of rose, sienna, and ochre with undertones of blue watercolor.

The model would eventually be identified as the reputed artist’s recent bride, Aline Charigot, in two separate poses. But was this truly the work of famed French Impressionist Pierre Auguste Renoir?

In the sweltering weeks following the Fourth of July, I was asked if I would work up a research paper to help to authenticate a late-19th-century pastel drawing whose present owner was certain it was a Renoir. My prospective client had purchased it for $150 at the Metropolitan Pavilion Antique Center in Chelsea in 1993. “At one of the booths there was a small Renoir etching that more than interested me,” my client told me in an email. “I kept going back. Then, on the third time, I saw a larger framed work of art leaning against a table. I asked if I could clean the glass and saw in the lower left corner a signature. It was in pastel. I bought it.”

The client had already undertaken considerable background work: He’d traced the piece back to the family that had owned it. “The 94-year-old mother said they owned a Renoir, and it was sold in the 1960s,” the client told me. (He contacted the woman’s daughter last year but the daughter could not confirm or deny her mother’s story.) He’d had an auction house appraise the work, then he’d consulted museum conservators and experts in Europe and the US, without conclusion. Up to this point, all these art world professionals, if they took him seriously at all, tended to disavow the drawing’s authenticity.

By the time I was contacted to join the search, he had expended considerable time and money to find someone with the appropriate expertise to authenticate his drawings, but his efforts on the whole had been rebuffed.

For a wild gamble on a favorable outcome that would prove the work authentic, I agreed to write a précis to present to a potential buyer. To begin, I emailed an inquiry and an image of the drawing to a former colleague at the Center for the Study of Modernism at the University of Texas at Austin. His interest in the work was at first academic: He cautioned the owner that fake Renoirs were everywhere—that canny, sophisticated forgers could credibly imitate all aspects of a masterwork down to the specific points of an individual artist’s distinctive style and technique (known as “facture”), the kind of paper used, and all other manner detail used to determine a work of art’s age. Additional inquiries yielded numerous gentle but firm warnings of fraud and the vagaries of the business side of the art world, which was described as largely an arbitrary enterprise.

Again and again I examined the photograph of the drawing my cleint had sent me. Its facture at first appears unlike Renoir’s Impressionism, though research reveals the artist’s late interest in the painter Rubens’ classical Rococo style. In the 1880s, Renoir repudiated Impressionism and began to strive for “an art free of purpose without literary interpretation.” Though increasingly troubled by advancing rheumatoid arthritis, he began to create compositions much more robustly definitive in volume and painstakingly articulate in surface clarity, in the manner of frescoes, which he had studied and helped repair on a trip to Italy. Renoir’s late Bather studies are reclining odalisques, economically spare and sensually distorted nymphs in a secluded glade having a wash.

So the style jibed with late Renoir. What about the material?

The machine-made paper on which the pastel was drawn was only available in a specific time frame. Renoir’s brother, Edmund, a printer for a graphic arts magazine called La Vie Moderne, had a roll of transfer paper used in lithography, called guillotage, used to transfer a drawing in litho crayon from the initial ground to the litho stone. It was a mix of softwood bleached sulfite with some hardwood and had a clay-based surface coated on one side that made it shiny and slick, in order to accept the oil crayon to be transferred to the stone for printing. Renoir, being frugal, apparently took the roll of paper to work out his Bather studies. He must certainly have realized its archival shortcomings—numerous accounts indicate there were issues of toxicity and the paper was discontinued. But by all indications Renoir got hold of his supply well before that. Further, the paper-making machine was destroyed sometime before 1890, so the paper could not have been made past that point.

“The paper and traits of the paper, the grain and the acidity of that date are so unique that they cannot be reproduced,” my client assured me.

Renoir’s house was robbed sometime in the early 1900s and a number of works stolen. The provenance, or list of sellers and buyers, of many of Renoir’s works moves forward from 1947, the years previous lost in the murk of artworks looted, stolen, or forced to be purchased at low prices by Nazi art thieves. The pastel in question lay in a storage facility in Florida for more than 40 years. One expert who’d examined the work even found evidence of ocean air residue on the glass.

Beguiled by the image of the pastel in a chrome-printed photograph, I spent hours deliberating the merits of the expert’s tests and testimonials. Finally I decided to go down to see the work myself.

This had been a summer of residuals and reversals—jobs increasingly fewer, a poignant relationship over. I needed to get on the road. After a few halfhearted efforts the night before at Nietzsche’s to interest somebody in sharing a ride with me, I drove to New York City.

No sooner had I arrived in midtown Manhattan than I found myself in the great maw of seriously indifferent commerce, the myriad side street truck bays and storefronts selling fraudulent fashion imports and cheap retail outlets regularly raided by the illegal-immigrant and copyright-infringement police. I parked briefly in a truck loading zone and walked maybe 10 feet from the curb to check the floor number of my client’s loft. I turned back just in time to see a parking cop zapping my registration for $115. Clutching the wretched violation document, I bolted to Brooklyn, where an obliging friend put me up.

The next day, car safely parked and belly full of bialy and coffee, I took the L train back into the city. Midtown, formerly alive with disorienting clamor, was now more or less deserted on an early Saturday morning. I buzzed the door.

Living in a 19th-century factory building loft in a commercial district of Manhattan has not changed since I sublet one in Chinatown more than 30 years ago while going to art school. My client had lived in similarly rigorous surrounds for longer than that, and gradually the familial had melded with the unforgiving dimensions of early sweatshop—oriental rugs and low sagging couches kept company with a brace of mounted staghorns and family heirloom photographs under a peeling tin-paneled ceiling. Cat hair firmly matted all horizontal surfaces.

The cloaking heat was remarkable—I remarked on it. We moved to the front of the living space and sat on the interior window ledge fronting the wrought-iron balcony. Below the tall lead-glass windows open as wide as they would go, the weekend traffic five floors down was beginning to pick up. My client reviewed what was by now a litany of affronts from museum curators, conservators, and experts in all areas of fine art authentification. The client had a clear plastic photo file of all the tests he’d had performed on the pastel and all the testimonials proffered.

He carefully laid out a full-sized color photo of the pastel on the paint-stained floor. “I can tell you that I believe the Renoir pastel to be a very important study that changed the style of Renoir’s nudes because of the logical and normal way he would have planned the creation of his masterpiece, The Bathers,” he told me.”

I stared but did not gape. The photo revealed in all aspects the quality of execution I associated with a masterwork. There was no hint of a forced effort—nothing poorly cast in form or feature. The figures held rigid poses yet were suppley rendered on the porcelain-like surface of the paper. And this was only a high-resolution photograph.

“Most of the Renoir’s drawings are behind glass in museums,” the client said. “The machine process created creases in all 30 of the ‘Bather’ series. They were made on the same side, the only side with the special grain.”

Women bathing was taboo-breaking subject matter for Victorian era painters: a way to get a naked babe into a picture without all the purience evoked by unadorned harlotry. Fantasies of women deshabilles had been the staple of figurative painting from Peter Paul Rubens on, with biblical and secular scenes of women going about with bits of their anatomy demurely or ravishingly revealed. Then in 1863 Edouard Manet painted Dejeuner sur l’herbe (“Luncheon on the Grass”). In it, a quartet of young men and women lounge in a leafy grotto, possibly intending to do more than knock back a few knickerbockers. But at the moment of the artist’s choosing, one woman is unabashedly naked and stares at the viewer amused, while the two men smirk with an air of faint detachment.

This was bravura painting and a public scandal. By comparison, other works of the time appeared chastely remote. It’s in this painting that the idea of the “moment”—the candid expression of a spontaneous, instant impression—was formed. Impressionism was all about that moment—the sense of heightened awareness that something was fleeting, moving quickly past, and yet held fast in the artist’s fixed vision, the luminosity of the paint catching the instant of that passing and moving the eye through mists of sentiment and romance to a revelation grounded in mortality.

By the time the subject of women under the “male gaze” gets to Piccasso, the bathing ruse had been well plumbed. Picasso’s 1907 painting, Les demoiselles d’Avignon (“The Young Ladies of Avignon”), brings figurative French painting back to its libidinous origins, “the dauntless sirens of the dark.” Picasso’s jagged, masked figures, naked in vertical shards of Cubist geometrics, stare out at the viewer with a spectral intensity and bored lust. The painting’s shocking incoherence was an outright sabotage of conventional representation.

Squinting, my head swathed in a bandanna to keep from dappling the piece with sweat, I tried to allay any doubt or hesitation I had as to the works veracity,suspended in a haze of possibility that the next few hours might deliver a true marvel—a modus interruptus in the history of one of the most popular painters of romantic sentiment and sensuality.

My client had done his carnival barker best to bring me to his bathing beauty. With enticing morsels of fact and logical supposition he had drawn me in. And now, with a practiced flourish, he closed the cardboard case and hiked it onto a high shelf.

My appetite well whetted, I ask him to take me to her. We walk 10 blocks crosstown to the meandering factory district known as Chelsea, now the height of the fashionable arts culture with outposts and annexes of famous merchants of clothes and accessories. There amid gaunt galleries with hyphenated names closed in the glazing heat of an August summer stood a block-long building appearing almost unnaturally active in the echoing canyons of Westside Manhattan: the U-Haul storage facility. Given the key in exchange for our IDs, we quickly passed through the sweating crowd waiting for their rentals into the huge garage bay to the freight elevator which, once we hunted up someone to run it, took us four stories up and out into a maze of corridors lined with locked storage vaults. We were grateful for the hint of air conditioning.

Once the vault was opened, my client drew on white cotton gloves and pulled out a slim, custom-made cardboard case and gently placed it on the concrete floor. Past the bubble wrap, the sealing tape, the exactingly folded glassine wrapping paper lay the original pastel drawing. I gaped like a wizard’s sleeve.

Mere privilege does not describe what I felt viewing the image at my feet. It was more like a kind of witnessing, being fully present at a singular event; it was something like seeing one’s child for the first time while realizing that it may not be one’s own. It was supremely paradoxical, gorgeous, glorious near exquisite, almost sublime—yet in a moment’s reflection it seemed also a bogus bounty, a charlatan denuded, a snare, a delusion, a canard.

There was no way to reconcile this. With all my will I wanted it to prove a true Renoir. I strained to see the master’s invisible hand. His previous career as young porcelain painter, a graphic designer, a fresco artist, and his entire ouevre as a founding painter of the French Impressionist school weighed on my inventory as an art historian. I was dumbstruck…almost in love.

I focused on every element of composition, every facet of facture: the positive space, the negative space, the foreground, the interstices between the two figures, hands, feet, elbows, knees, the model’s limpid features, their hair almost strand by pencilled strand, the nails of fingers and toes, the shading, the palpable weight of limbs where here and there the chalk ground was abraded by a stylus just enough to reveal the surface underneath, giving the subtle impression of light falling on flesh—just a few quick lines through the pigment.

“Renoir scratched the paper with a needle to make the white appear through the pigment from the paper underneath, a technique also found on my pastel,” my client said.

The work appeared so assured, even quickly done, the figures anchoring the space in languid ease, nubile and innocent (perhaps), but inspiring one to join them.

That was the whole of it—here in a cramped sun-lit vault in a labyrinth of corridors, I stared down into a pastel drawing from the 19th century and wanted to dive in.

This is the first in a series of articles on the authentication of a pastel drawing attributed to Pierre Auguste Renoir.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n35 (Fall Arts, week of Thursday, September 2) > Authenticity This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue