The Saddest Valentine's Day

by Buck Quigley

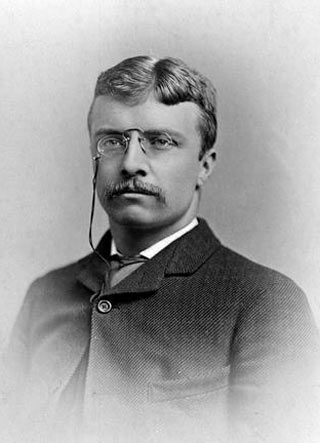

February 14, 1884—the day the light left Teddy Roosevelt’s life

In February, 1884, the fog in New York City was so thick the gas streetlamps appeared to be veiled behind gray curtains. But inside the luxurious walls of the mansion located at 6 West 57th Street, there was excitement in the air. A baby was on the way, and women’s voices echoed off the ornate dark hardwood surfaces and the gaudy displays of antlers and horns taken as trophies by the man of the house—who was away in Albany, working.

Just four years earlier, on Valentine’s Day of 1880, Alice Hathaway Lee and Theodore Roosevelt had publicly announced their engagement. Though he described it as love at first sight, winning the young beauty’s heart had not been an easy task—she initially declined his proposal, and put him off for six months before relenting. They were married on October 27 of that year, on his 22nd birthday.

Now he was a ball of energy, working 14-hour days as a New York State Assemblyman in Albany, making a name for himself as an aggressive young politician who spent a half hour daily in actual sparring matches with a prizefighter in his rooms in the state capital. It was all part of his relentless pursuit of rugged manliness that included travels to the Dakota Territory, where he bagged a buffalo head to decorate his Eastern home.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt’s 22-year-old bride was in her ninth month of pregnancy. So that she would not be alone while he toiled away at his legislative duties, he sublet their brownstone and moved her into the family mansion with his mother, Mittie, and sister, Bamie. Corrine, another sister who’d recently given birth, joined them there. The idea was to run a nursery for the two infants on the third floor.

On Wednesday, February 13, a telegram arrived in Albany bringing the joyous news. Late the night before, the 25-year-old Roosevelt had become a first-time father of a baby girl. Colleagues crowded around him on the Assembly floor to shake his hand. He requested a leave of absence, to take effect after acting on some 15 bills on the day’s agenda. One can picture his famous teeth lighting up the room as his pride swelled.

As the business of the day wore on, a second telegram arrived. The text of the transmission has been lost, but upon reading it his countenance is said to have changed. He rushed to the train station, and was soon aboard a locomotive crawling down the Hudson Valley through thick fog.

He arrived at Grand Central Station around 10:30pm, and ran on foot into the murky darkness toward the mansion, where the gas lamps were burning brightly on the third floor. When he arrived, his young wife was nearly comatose. He took her into his arms as he learned she was dying of Bright’s disease, a broad term of the day, which meant her kidneys were failing. The symptoms had likely been masked by her advanced pregnancy, but now, as her organs shut down, it was only a matter of time. She could barely recognize him as church bells struck midnight. It was at last Valentine’s Day, but Roosevelt’s private agony had only just begun.

Downstairs, 48-year-old Martha “Mittie” Bulloch Roosevelt, Teddy’s mother, was lying in bed as her temperature soared and the tell-tale rose spots that accompany typhoid fever bloomed on her moonlight skin. She remained a beautiful Southern belle until the end, her face framed with hair as dark as night. At two in the morning, Roosevelt was informed that the time for last words with her was at hand. He reluctantly set his wife’s head down upon the pillows and descended the heavy wooden staircase.

As he looked down at Mittie, he must have had time to reflect upon the last time a visit home had been undertaken with such urgency—six years previous, upon the death of his father, the great hero of the young man’s life. Now, he repeated the words his brother had spoken only a few hours earlier, convinced of their truthfulness: “There is a curse upon this house.” At three in the morning, Mittie died. Roosevelt returned to Alice and took her again into his arms.

As dawn broke, the fog continued to thicken until the sky opened up mid-morning in a withering downpour. Sunlight briefly flooded through the windows and glinted off the rooftops before the clouds again converged. The temperature rose quickly toward 60 degrees, and the humidity began to increase, making things all the more uncomfortable on the third floor. Mercifully, after noon, cool dry air began moving in from the north, and the skies began to clear. At two in the afternoon, cradled in his arms, Alice died at the age of 22.

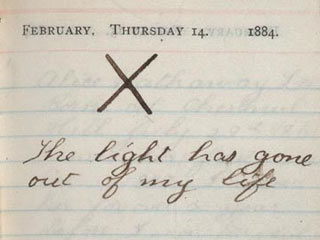

A monumentally prodigious writer, Roosevelt marked his diary for Thursday, February 14, 1884, with a large, dark “X.” He wrote just one line below it: “The light has gone out of my life.”

Alice, above right. and Mittie’s, below right, funerals took place simultaneously in the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church two days later, with Roosevelt still stunned into a bewildering state of childlike confusion that concerned friends and family members alike. He was unable to understand condolences, and showed no interest in his newborn daughter. He spent his time pacing in his room. Two days after the funeral, he wrote one paragraph in his diary recapping the important dates in their relationship, and describing her untimely death in his arms just hours after his mother’s death. “For joy or sorrow, my life has now been lived out,” he concluded.

Roosevelt worked aggressively to obliterate all memory of Alice from his life. He removed photographs of her, and went through old letters, erasing every reference to her until the pages were worn through. He never spoke of her again, even when their daughter, Alice, became old enough to wonder about her mother, who’d died so swiftly after she was born. Painful nostalgia, Roosevelt reasoned, had to be supressed “until the memory is too dead to throb.” He would never again tolerate her name being mentioned in his presence.

He, of course, would go on to remarry, start another family, and be sworn in as the youngest president of the United States in Buffalo, upon the death of William McKinley in 1901. His daughter Alice grew into a stunning beauty like her mother and inherited his outspoken and independent nature, which put her ahead of her time. When her father was still governor of New York State, his second wife felt that her wild nature would benefit from a stint in a conservative New York City school for girls. “If you send me I will humiliate you. I will do something that will shame you. I tell you I will,” she warned her father.

During his presidency, she kept a pet snake, liked to smoke cigarettes, partied late into the night, and enjoyed gambling—habits that made her a beloved national character in her own right. She was known affectionately by the masses as “Princess Alice.”

She eventually married a congressman from Ohio, though she gave birth to a daughter fathered by another lawmaker with whom she was conducting an ongoing affair. She possessed an intolerance for injustice and a stinging wit. “If you can’t say something good about someone, sit right here by me,” she used to say. Another time, when asked by a member of the Ku Klux Klan to take him at his word, she replied, “I never trust a man under sheets.” During a 1974 interview on 60 Minutes, she bragged that she was a hedonist.

Alice Lee Roosevelt Longworth died in 1980, at the age of 96.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n6 (Valentine's Day Issue) > The Saddest Valentine's Day This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue