Beebo Brinker & The Lesbian Pulps

by Anthony Chase

Ann Bannon, pulp novelist, talks about her stories of love between women

Next week, Buffalo United Artists (BUA) will open their production of The Beebo Brinker Chronicles, by Kate Moira Ryan and Linda S. Chapman. The play is based on a series of lesbian pulp novels by Ann Bannon, published between 1957 and 1962. These books were the first representation of women loving women that the post-war generation had seen, and in that regard, they helped lessen the deadly isolation so many had felt. They also contributed to a consciousness that was evolving into a full-fledged gay rights movement, and paved the way for the generation of lesbian writers that was to follow.

Still, despite their undeniable influence and widespread appeal, Bannon would later recall that her books and other lesbian pulp novels of the era were entirely ignored by the mainstream press. They were never reviewed for the New York Times Review of Books. They were not listed on official best seller lists. Even law enforcement of the late 1950s and early 1960s paid no attention to Bannon and her contemporaries.

“We were lavishly ignored,” recalled Bannon, “except by the millions of people who bought our books in drugstores, airports, train stations, and newsstands.”

Bannon stopped writing in 1962. She was living as a young married housewife, raising her small children in the suburbs of Philadelphia. In many ways, the world went on as if this moment in literary history had never occurred.

Imagine the surprise of BUA producer Javier Bustillos when, shortly after announcing the BUA production of Beebo Brinker, he received this email message: “I’m delighted that you’re planning to produce The Beebo Brinker Chronicles in February and March 2010. Let me know if there’s any way I can support you. Beebo would love knowing that you are bringing her story to life in Buffalo! Warmly, Ann Bannon.”

Bustillos wrote back immediately, and this interview is the result.

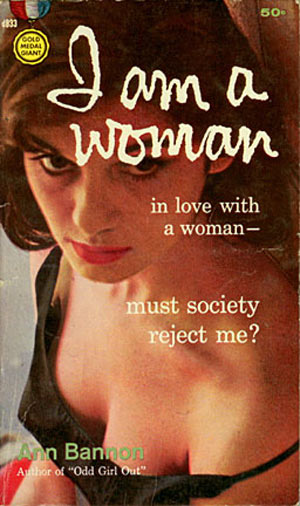

The play conflates the stories told in three of Bannon’s five original paperback novels (I Am Woman, Women in the Shadows, and Journey to a Woman). In the language of the pulps, the play follows “the lives and loves of Laura, Beth and Beebo as they navigate uncharted territories of desire. Beth and Laura, secret lovers in college, went separate ways after graduation: Beth married and had children; Laura moved to New York. Both pine for each other, but before they can reunite, they find themselves entangled in the web of Beebo Brinker, a butch denizen of the bars with a soft spot for young lesbians fresh off the bus.”

Whew!

Since the announcement of The Beebo Brinker Chronicles in Buffalo, I have been astonished by the wide-ranging interest in the books. Not only among lesbians. Not only women. But also among gay men and straight men. Older people; younger people. My own mother, a patrician woman in her 80s, is fascinated by the story of Ann Bannon and the lesbian pulp novels that she wrote.

“That probably goes back to the original publishers,” Bannon reasons, speaking from her home in California by telephone. “Lesbian pulps were marketed to a broad range of readers. Actually, I took my writing very seriously and worked hard at it; I wanted covers for my books that would be appropriate for quality fiction. But the authors had no control over the titles of our books or the cover art. The publishers knew how to reach out to the readers, whether it was a businessman looking for a little excitement in this life; or a housewife, down on her knees, waxing the kitchen floor but looking for the same thing. The pulp publishers understood the market place.”

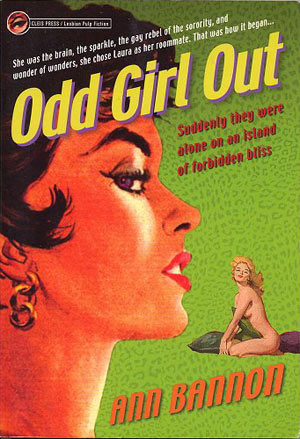

Indeed they did. Bannon would not know it for another 30 years, but Odd Girl Out was actually the second-highest-selling novel of 1957!

“The books were sold wherever magazines were sold,” says Bannon, “and they had to sit beside the cowboy novels, the science fiction, the cops and robbers stories. And they had to be distributed through the US Postal Service, so the publishers found ways to make the books attractive to our readers without being overly explicit; they communicated to the readers with a kind of code. My first book didn’t even contain the word ‘lesbian’ because I was so inexperienced I didn’t even know it! But with titles like Odd Girl Out, and Journey to a Woman, and with covers that featured two women, and so on, our readers found us.”

“I did know that I was a successful writer,” says Bannon. “One year I earned as much as my husband, penny for penny!”

While Bannon’s husband liked the income, he did not like the stigma that came with lesbian pulp fiction.

“He married a sweet, innocent, 22-year-old girl who had just graduated from college,” recalls Bannon. “He was a good-hearted guy, and I know he did love me, but my husband was a controlling person. Here I was writing lesbian novels behind his back, and he was deeply concerned that this was a threat to his marriage. He also did not like having to explain to friends, ‘Oh, Ann is busy writing a book,’ and have them ask, ‘Really, what kind of book?’ He’d laugh it off and say, ‘Oh, she thought she’d try her hand at pulp fiction!’”

In fact, “Ann” was a master of the genre!

“In time, my children were old enough to become inquisitive about why Mommy was spending so much time at the typewriter; and my husband was increasingly hostile toward my work. I had done a couple of workshops for the Mattachine Society on writing gay and lesbian fiction. I had spoken to the Daughters of Bilitis, and a couple of times a woman from that group would find out my real name and where I lived. A woman would show up at my door saying, ‘I could tell from what you were saying that you were calling out to me!’ and that was upsetting. So, when the opportunity came to go to graduate school, I stopped writing. I guess it was a matter of one door closing and another one opening up.”

Bannon would earn a Ph.D. in linguistics from Stanford. She taught at the university level and eventually became an associate dean at California State University, Sacramento. Because she had written under a nom de plume, she was generally unrecognized as a novelist and considered her literary career to be an episode buried in her remote past. (Her marriage ended in the 1980s.) Over the course of time, however, she began to realize the enormous impact of her work.

It was not until her retirement from academia, however, in the late 1990s, that Bannon started to reconnect with her literary legacy. She traveled the country, promoting the Cleis Press editions of The Beebo Brinker Chronicles (2001-2003), giving numerous radio and television interviews, writing numerous essays, and finding that she was a veritable rock star of pulp fiction nostalgia and scholarship.

The stage version of the Beebo Brinker stories has added a new dimension to interest in Bannon. The profile of the New York production was raised considerably when Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner signed on as executive producers.

While the tone of the books is serious, the play is high camp.

“All of the dialogue from the play comes directly from my books,” says Bannon. “I think the camp element is the result of the passage of time; the repressiveness of the era is so out of step with the way we think today. But there was always comedy in the books—especially in Jack’s lines. There are one or two contemporary inventions—for instance, when Jack admonishes Laura not to fall in love with a woman who might be straight, he says, ‘Maybe she doesn’t like bearded clams!’”

Bannon laughs. “I never could have written such a line; I don’t know the up-to-date slang!”

Now that she finds herself a contemporary celebrity, Bannon notes that young people have difficulty imagining the extreme repressiveness of the 1950s.

“It was scary to write about lesbianism in the 1950s,” explains Bannon. “Young people will ask me why people didn’t fight back sooner. They do not realize that everything in society was aligned against the nascent gay community—everything from the medical establishment to the postal service. You were sick, you were wrong, you were a corrupting influence. They even looked at history and anywhere there was failure and decay, the cause was gay people. Your church would excommunicate you. Your family would disown you. Your employer would fire you. A person risked everything just by coming out. That degree of repressiveness is difficult for young people to imagine today.”

What does Ann Bannon think of the play?

“I think they did a marvelous job,” she says. “Out of necessity, they had to eliminate characters and streamline the plot, but they treated the material with great affection and respect. I am very pleased with the play.”

The Beebo Brinker Chronicles has been directed by Chris Kelly. Kate Elliott plays Beebo; Katie White is Laura. The play also stars Nicole Cimato, Nick Cocchetto, Jamie Doktor, and Doug Weyand. It opens on February 19 and runs through March 13. Call 886-9239 for ticket information.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n6 (Valentine's Day Issue) > Beebo Brinker & The Lesbian Pulps This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue