Next story: Scorecard: The Week's Winners and Losers

Seven Days: Each one drawing closer to a Paladino presidency

by Geoff Kelly, Louis Ricciuti, Buck Quigley

Garbage in, garbage out

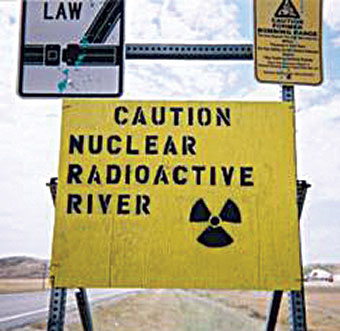

This week the New York Times published Ian Urbina’s three-part series of articles on a subject we’ve been obsessing over on these pages since the new year: the disposal of wastewater from hydrofracked natural gas wells.

Urbina’s kickoff piece in Sunday’s Times dealt exhaustively with the radioactivity of wastewater produced by deep-well, horizontal hydraulic fracturing. The process entails pumping millions of gallons of water mixed with sand and chemicals a mile or more underground to force open fissures in shale beds, thus releasing trapped natural gas. Some of the frack fluid returns to the surface, bringing back with it radioactive materials like radium-226 that occur naturally underground but are dangerous when brought to the surface or if ingested in drinking water.

Urbina missed an aspect that we think is important: It’s not just frack fluid returning to the surface that’s radioactive. The frack fluid is intentionally made radioactive by gas drillers before it’s pumped into the ground.

In order to map the fissures into which they are pumping frack fluid, drillers will add highly radioactive tracer isotopes to the water, in addition to the cocktail of chemical additives, many of which are known carcinogens and which environmental activists fear are migrating into streams and wells and other drinking water sources. The tracer isotopes are used in exactly the same way that doctors use them in hospitals: A high-emitting isotope with a short half-life (such as scandium-46 and iridium-192 in wells) is used to tag the fluid so that its progress can be tracked, thus illuminating to some degree the underground landscape of a well, just as a doctor uses a high-emitting isotope (such as technetium-99m) to track the flow of a fluid through the body’s organs or bloodstream.

The amounts of these materials used may be small, and because of the short half-lives, the nuclear industry commonly claims that their potential health impacts are negligible. But the decay process of these supposedly harmless tracer isotopes yields other elements, such as heavy metals, which are both chemically and radiologically toxic, especially if ingested. The 2005 BEIR VII (or “Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation”), a continuously evolving report released by the National Academy of Sciences, established a new understanding of the dangers posed by even minimal exposure to ionizing radiation: namely, that there is no such thing as a safe dose.

Perhaps this is one reason that the exact composition of some fracking fluid additives is a closely held, proprietary secret.

All of this garbage in and garbage out recalls one of many documents that drew this paper into the issue of legacy radioactive wastes, their impacts, and their disposal. In 1944, in a memo to Captain Emery L. Van Horn of the US Army Corps of Engineers, the superintendent of the Linde Ceramics plant in Tonawanda described the different courses he might take to dispose of caustic liquid wastes contaminated by radiation, sometmes called “liquors.” The first option, wrote A. R. Holmes, was to discharge the effluent into a storm sewer that emptied into Two Mile Creek, which runs past a public park and into the Niagara River. Alternately, Holmes said, the effluent could be pumped into wells on Linde’s property, from which it would presumably disappear into the water table.

“Plan 1 is objectionable,” Holmes wrote, “because of probable future complications in the event of claims of contamination against us. Plan 2 is favored because our law department advises that it is considered impossible to determine the course of subterranean streams and, therefore, the responsibility for contamination could not be fixed.”

The Corps of Engineers agreed, apparently, and over the next two years Linde pumped nearly 50 million gallons of radioactive liquors into shallow wells on its property. Presumably it seeped into the aquifer, made its way to Two Mile Creek and the Niagara River, and flowed over the Falls—unaccountable and unaccounted for, carried by unseen waters.

That was the nexus of government and industry 67 years ago: an object lesson for today’s environmental activists as they press regulatory agencies to evaluate the dangers of fracking and hold gas drillers accountable for the damage their industry does.

New York State has put a hold on permits for deep-well, horizontal hydraulic fracturing until June. But vertical fracking continues, attended by many of the same environmental concerns.

—geoff kelly & louis ricciuti

The high cost of lowering the deficit

Last Thursday, three members of Buffalo’s Common Council held a quickly assembled press conference to urge Western New York’s Congressional delegation to fight against the Obama administration’s proposed budget cuts to domestic programs that benefit poor and middle-class communities.

Niagara District Councilman David Rivera urged the region’s representatives and senators to “put people first,” ahead of mammoth infrastructure projects like the Peace Bridge plaza expansion project, which he called “poorly planned and lacking neighborhood support.” (This was a reference to a quote from Congressman Brian Higgins in a Buffalo News article last week, in which Higgins vowed to find federal money for the expansion project. That remark seems to have precipitated the press conference.) Rivera, joined by Fillmore’s Dave Franczyk and Delaware’s Mike LoCurto, urged the delegation to defend instead programs like the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, and community block grant programs.

The proposed cuts will have an especially profound effect on Western New York, according to a report issued this week by the Partnership for the Public Good. According to the PPG report, 132,083 households in eight Western New York counties received $53,275,637 in federal heating assistance dollars last year. Erie County households used LIHEAP at a rate of $58 per person, which is 32 percent higher than any other state in the country. LIHEAP recipients in Cattaraugus County use the program at a rate of $73 per year.

And those already high numbers may not provide an accurate picture of the need for assistance in this region. In 2009, LIHEAP distributed nearly $100 million to almost 300,000 Western New York households. The high usage in Western New York is attributable to our aging housing stock and high poverty rates.

The Obama administration has proposed a 50 percent cut in LIHEAP funding. So next year $25 million will have to do, where $100 million was distributed two years ago and $50 million was distributed last year.

According to the PPG study, the proposed budget cuts could cost Western New York $1 million in Community Service Block Grant funds and another $6 million in Community Development Block Grant funds. And the $125 million cuts proposed to the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative could endanger remediation plans for the Buffalo River near its mouth on Lake Erie.

“A budget is a document of priorities,” Rivera said. “Our question to Western New York’s Congressional delegation is this: What are your priorities?”

—geoff kelly

UB 2020 bill passes in state Senate

As we go to press, the New York State Senate is expected to approve a revised version of the UB 2020 bill that has failed to pass in the State Assembly for the past three years.

A spokesperson for State Senator Mark Grisanti, who introduced the amended legislation, says Grisanti will be voting for it. The new bill purports to limit tuition increases for poorer students, while still allowing huge increases for professional degrees.

On February 1, Grisanti admitted to Artvoice that he had not yet read the bill, even though he’d gone on the record in January with the rest of the Western New York delegation in support of it.

“I am happy to be standing with my Senate and Assembly colleagues today to urge Governor Cuomo to help UB become the world-class university and economic driver for Western New York that it has the potential to be,” Grisanti said at the time. “I know the Governor supports UB 2020 and I hope he will demonstrate that support in his executive budget proposal.”

He had not returned further phone calls as we went to press.

Meanwhile, other parts of the bill continue to give UB financial freedom over bonds and real estate deals with private concerns. This is the public-private partnership business that raises some eyebrows.

To see how this might work, let’s look at last year’s Senate bill that authorized the State University Construction Fund to transfer $132,000,000 in SUNY capital construction funds to the Buffalo 2020 Development Corporation “for the purpose of constructing, acquiring, or creating a Clinical/Translational Research facility on the downtown campus, and incubator facility on the downtown campus, the UB Gateway project, and reimbursing the University at Buffalo Foundation for property acquisition for the Educational Opportunity Center and the UB Gateway project…”

The University at Buffalo Foundation claims to be beyond the reach of the Freedom of Information Law (FOIL), and as a result we are awaiting a decision from Judge Patrick H. Nemoyer to see if he agrees that they are a private entity beyond the reach of the press and public. They appear to be quite capable of receiving millions in state funds. The case is a continuation of FOIL requests we initially filed last summer, only to be denied access by their lawyers at Hodgson Russ.

What is the Buffalo 2020 Development Corporation? According to UB spokesman John Della Contrada, it is a not-for-profit corporation that was designated by the New York State legislature for the disbursement of the capital appropriation for the development of UB’s downtown campus.

Who are the directors of the Buffalo 2020 Development Corporation? James Weyhenmeyer, the chairman, is also vice president and managing director of the Technology Accelerator Fund at the SUNY Research Foundation. Satish Tripathi, the vice chairman, is also provost and executive vice president of Academic Affairs at SUNY Buffalo.

Buffalo 2020 Development Corporation board members are: David Dunn, vice president for Health Sciences at SUNY Buffalo; Scott Nostaja, senior vice president and chief operations officer at SUNY Buffalo; John J. O’Connor, senior vice chancellor for Research and Innovation, secretary of the University, and president of the Research Foundation of SUNY; Edward P. Schneider, executive director of UB Foundation; and John B. Simpson, the outgoing UB president who since his resignation has been named SUNY Buffalo “president emeritus.”

In addition to their SUNY salaries, Tripathi, Dunn, Nostaja, and Simpson collect generous stipends from the UB Foundation.

On February 10, I filed a FOIL request to them all, asking for “a reasonably detailed current list by subject matter, of all the records in the possession of Buffalo 2020 Development Corporation as required by Section 87.3 of the Freedom of Information Law.” I also asked for the certificate of incorporation, bylaws, meeting minutes, and records of all paid or unpaid employees with job title and salary information, as well as all 990 tax forms they’ve filed.

On February 18, I received a reply from Terrence M. Gilbride at Hodgson Russ, who identified himself as corporate counsel for the corporation: “As a private not-for-profit corporation, Buffalo 2020 Development Corporation is not subject to the provisions of the New York Freedom of Information Law…”

By the time you read this, the new UB 2020 bill likely will have passed in the State Senate. It is just as likely that the State Assembly will vote it down again. In light of the obvious lack of transparency still built into the bill, that may be a good thing, if New Yorkers are to retain any financial oversight of the state university system they’ve poured billions and billions of dollars into since 1948, when it was created “to provide to the people of New York educational services of the highest quality, with the broadest possible access, fully representative of all segments of the population in a complete range of academic, professional and vocational postsecondary programs.”

—buck quigley

Department of long shots

Also last Thursday, while Rivera, Franczyk, and LoCurto where taking exception to Higgins’s priorities on the 14th floor of City Hall, a candidacy was born just across Niagara Square, on the steps of the Buffalo City Court building.

There, Anthony L. Pendergrass, Esq.—who describes himself in a press release as a “noted and esteemed Buffalo Attorney”—announced that he will be a candidate for a seat on Buffalo City Court in this fall’s elections. Way to get in there early, Mr. Pendergrass.

You may have noted Pendergrass for his role as attorney for Police Officer Cariol J. Horne. He ran an unsuccessful write-in campaign against Fillmore District Councilman Dave Franczyk in 2003.

—geoff kelly

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v10n9 (Week of Thursday, March 3) > Week in Review > Seven Days: Each one drawing closer to a Paladino presidency This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue