Our Green Moment

by Bruce Fisher

Focusing a movement to regenerate small cities

Catherine Tumber’s hopeful new book, Small, Gritty, and Green: The Promise of America’s Smaller Industrial Cities in a Low-Carbon World, should be required reading for every community conversation about the future of Rust Belt cities. Tumber, a journalist who hangs her hat at the Community Innovators Lab at MIT’s urban planning department, connects the conversations about Rust Belt economics and politics in some of America’s most distressed metro areas with the new global realities of oil.

Hers is a short book that is plain-spoken and comprehensive, and she makes it clear right from the start that she accepts the idea that big change is just about to be upon us because carbon-based fuels are going to have to be replaced very soon. That’s a good preface: If you accept the idea that many economists, physicists, and even the US military have accepted—namely, that our dependence on fossil fuels cannot continue, and that long-established, still-predominant patterns of sprawling land use are therefore going to have to end—then you can accept much of what follows in her exposition. But even if you accept Daniel Yergin’s analysis that constant innovation in energy production means that it will be four or five decades before anything has to change, and that, in effect, oil-driven personal transportation will continue to shape American life, then this book is still a good guide to the changes underway throughout the old Northeast and Midwest.

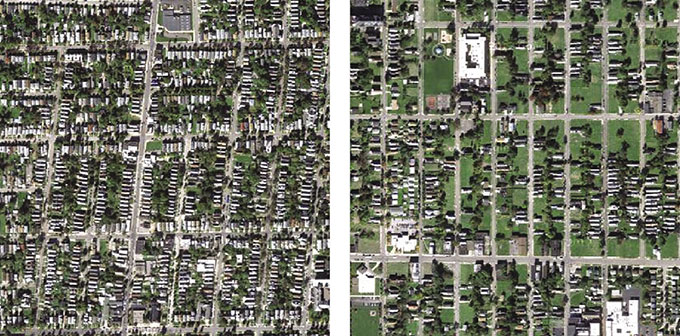

What becomes clear early on in Tumber’s analysis is that many of the small cities of the American Midwest are beginning to allow increments of innovation to move from concept to design to implementation, in part because taxpayers are increasingly aware that another taxpayer-funded stadium, or convention center, or “festival retail” district, won’t be the thing that replaces the long-shuttered automobile-assembly plants, slaughterhouses, steel mills, and manufacturing operations that defined the industrial age for 150 years or more of their towns’ histories. Tumber actually went out and visited Rust Belt cities in preparing this book, as well as reading all the old literature on “Middletown,” the classic study of the golden age of archetypical Muncie, Indiana. This comparison leads us to a harsh thought: As much as we would like to compare Buffalo to Chicago, which is the successful global city that we did not become, the rest of the Rust Belt would be wiser to learn about the rise and fall and now the adjustments underway in Muncie, and about the experiments in Youngstown and in Flint and in Syracuse. That’s because all these towns share all the characteristics that have so far doomed them: racial polarization, sprawling low-density suburbs, abandoned and largely empty centers, and both the positive and burdensome legacies of the industrial age. Now, though, they all share a natural asset that distinguishes them from the mega-cities that we all in our hearts want our hometowns to be: namely, lots of empty land right in our middles. We all have weak cores.

As many activists and local-think folks in the old Northeast and Midwest have already concluded, Tumber thinks that it’s the very availability of land inside old middle-sized cities that is itself a great positive asset for future economic growth. But moreover, Tumber voices the hopeful opinion of many, which is that “we are on the brink of a third industrial revolution,” one that will be focused on renewable technologies “such as clean-fuel automotives, trains, and windmill, solar, and hydropower components—for which there will be real market demand in a low-carbon economy.”

Land-banking?

This week, Buffalo and six other communities will find out if a key tool for making that economic potential happen—the new land-bank designation that Buffalo and Erie County at long last applied for jointly—will be granted by New York State’s premiere economic development operation.

Land-banking is one of those mind-numbing terms for a concept that many of our pro-development, pro-growth civic boosters cannot stand—namely, adjusting to the reality that redevelopment won’t work because there is an insane mismatch between supply and demand. We in the Rust Belt inhabit what Bruce Katz of the Brookings Institution termed “weak-market cities.” We inhabit shrinking metro regions. If the housing bubble hadn’t burst so devastatingly in 2008, outmigration from Upstate New York, western Pennsylvania, and from most of Ohio and Michigan would have continued at the break-neck pace of the previous three decades. That outmigration has slowed not because there is economic growth here, but because the bubbling economies of the Sun Belt frothed out.

So that leaves us here, with jobs to do even if there are still not enough jobs. One of the hopes is that the land-banking process will mitigate one of the more destructive processes of the Rust Belt will stop—namely, the sequence of housing abandonment in old inner-cities and inner-ring suburbs while housing continues to get built farther and farther from the urban core, leaving too many structures in inventory with too few buyers, and too many municipal structures (cities, towns, villages, counties, school districts) to raid one another for taxpayers in order to sustain the unsustainable.

The land-bank movement began in Flint, Michigan, when a local elected official named Dan Kildee figured out that piecemeal redevelopment of the vast acreages of abandoned industrial space in that town was getting it exactly nowhere, and that a new approach was needed. There is a version of land-banking happening in Youngstown, Ohio, that may not be what many mayors like because Youngstown has decided to stop providing services in wide swaths of territory within city limits. Detroit has its own version of the practice. Land banks stop a practice that Buffalo and Erie County have tried as a coping mechanism for the problem illustrated by Dr. Wende Mix’s map—the problem of massive tracts of nearly worthless properties getting the same human and physical services as actual functioning neighborhoods. Our coping mechanism has been to try to collect all the unpaid taxes by selling off the tax liens to collection agencies that track down the delinquent owners, many of whom play the “in rem” game, of letting their properties go to the annual auction, and then buying them back for less than what they owed in back taxes.

The better responses have been based on gathering up all those abandoned or wrecked parcels, having a not-for-profit or government entity aggregate them and acquire (most controversially) remnant houses from the last elderly homeowner on an otherwise bulldozed block, and putting together big inventories of land that eventually, as time and funds permit, get cleaned up, grassed-over, and made ready for a new use for which there is an actual economic demand.

Quibblers will argue that Tumber’s book is too positive, too hopeful, and that she is too willing to accept that the mere need for a greener, less carbon-based world will actually get us there. I endorse Tumber’s analysis. There is good evidence in northern Europe, and in China, and as near to us as Syracuse, that a lower-carbon economy provides good jobs. They are different jobs than what the banker-developer-speculator hegemony of New York State’s political class is accustomed to delivering, but they are real. Urban agriculture is for real, too, as a recent Ohio State University economist argued by reviewing the potential of utilizing abandoned real estate in Cleveland (population loss 17 percent since 2000) as farmland. As for Tumber’s argument that manufacturing may be a spring-back mode for the Rust Belt, I defer to the experience of industrialists who note that industrial plants that used to require thousands of workers now, because of technology, require merely dozens.

But this new sensibility that Tumber reports is growing political legs in some mid-sized Rust Belt towns, and a sober accounting of how much more efficient it could be for taxpayers to fund services in more densely settled and re-setteled areas will be good conceptual tools for the future of any place that can push the green alternative. We are trending toward a more comprehensive awareness of the economic relevance of adaptive re-use as a preferred development alternative, of density as an energy-efficiency strategy, and of urban farming as a regional economic-development strategy. We are still stuck in a Rust Belt political paradigm of localism that is, frankly, racialized around schools. Breaking that paradigm down may require a different political paradigm than the one we have, or are likely to have.

Bruce Fisher is director of the the Center for Economic and Policy Studies at Buffalo State College. His new book is Borderland: Essays from the US-Canada Divide, available at bookstores or at www.sunypress.edu.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n20 (Week of Thursday, May 17) > Our Green Moment This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue