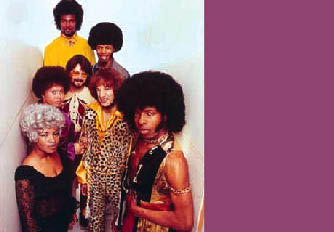

Remastered on the Sly: Sly and the Family Stone: Remastered Editions

by Joe Sweeney

The Grammy Awards have never been a bastion of good taste. Hell, “My Humps” won one. But last year the show reached a new low when it “paid tribute” to Sly & the Family Stone. First, a medley of Sly songs was soundly butchered by such artistic luminaries as Fantasia, will.i.am, Maroon 5 and the throatily atrocious Joss Stone. Then, out came a hapless, 63-year-old, blond-mohawked Sly, who looked uncomfortable and scared as he pretended to play the keyboards to “I Want to Take You Higher.” When he sang, his voice seemed strong, but his mic was almost inaudible in the mix. Imagine J.D. Salinger trying to give a reading, only to be drowned out by Tom Clancy. Before the song ended, Sly jumped off his raised platform, gave an awkward salute to the crowd and ran off stage. You could practically see the words “What was I thinking?” running through his mind. Chances are, this shameless exploitation of Sly will be the last time we see him on a major stage, which is depressing to say the least. Luckily, a series of beautifully remastered Sly & the Family Stone records have arrived to wash out that bad taste in your mouth.

To the uninitiated—and the folks that just own Greatest Hits—these discs should be earmarked as your next musical journey. In his prime, from 1968-1973, Sylvester Stewart defined original. He was too unruly for Motown, too focused for Haight-Ashbury, too happy for the protest crowd and too sexy for church, but his music featured elements of all those scenes. It just happened to transcend them as well.

If you think that Sly’s tunes are nothing more than a good time, consider this: His career arc mirrored that of society at large. At the height of flower power and the civil rights movement, Sly & the Family Stone signed with Epic Records and released a trilogy of rambunctious, defiantly positive LPs. If you want a summation of Sly’s uncanny ability to write socially conscious party songs, look no further than the first lyric he ever laid on wax: “I know how it feels to expect a fair shake/But they won’t let you forget that you’re an underdog/And you gotta be twice as cool.” This rumination on black social struggles is coupled with a horn arrangement of the children’s song “Frère Jacques,” a combination of consciousness and playfulness that cemented Sly & the Family Stone as “something different” from the get-go.

The reissues of this first-phase trilogy, A Whole New Thing (1967), Dance to the Music (1968) and Life (1968), all sound spectacular. The bonus tracks are mostly instrumentals and mono singles, so don’t expect any hidden gems (with the exception of a rollicking cover of Otis Redding’s “I Can’t Turn You Loose” from the Dance to the Music sessions). But even if they don’t reveal anything else, these remastered versions capture a young, astonishingly energetic band destined for bigger and better things. As a whole, these albums are the opening act to Sly’s stratospheric 1970s masterpieces, but Christ, what an opening act.

The group’s fourth record, and true commercial breakthrough, was Stand! (1969). By boasting sugar-coated pop smashes (“Everyday People”), provocative social commentary (“Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey”) and a sprawling, pointless jam session (“Sex Machine”), Stand! serves as a bridge—between Sly’s young, exuberant period and the brilliant, narcotic haze of his downward spiral. Once again, the extra tracks on the remastered edition aren’t anything to write home about (three mono singles, an instrumental and the cookie-cutter soul of “Soul Clappin II”). But it’s still worth getting, if only for the pristinely mixed version of “Sing a Simple Song,” a stone cold groove if there ever was one.

Once the 1970s hit, so did a whole pile of disillusionment (Vietnam, Watergate, etc.). It seemed like the messages of love, optimism and equality that defined Sly & the Family Stone, and the 1960s in general, hadn’t changed a damn thing. As he fell deeper and deeper into drug addiction, Sly shut himself off from the world, recording in an attic studio that was only reachable by a hidden staircase.

When his overdue fifth album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) was released, listeners discovered that Sly Stone wasn’t a happy camper. Instead of another slab of glorious party music, they were greeted by a brooding, existentialist statement: “Feel so good inside myself/Don’t wannamove.” This line, from the opening track

“Luv n’ Haight,” is Riot in a nutshell. The songs are insular and dark, the production is minimalist and muddy, and the whole thing is a heavy, slow-burning head trip, with no respite to be found. Just when you think a ray of light is poking through on the track “(You Caught Me) Smilin’,” Sly throws down the curtains with the closing line, “In my pain/I’ll be sane to take your hand.” Epic/Legacy gives Riot the mastering treatment it so richly deserves, and tacks on three untitled instrumentals from the infamously long and aimless Riot sessions. While these jams may not blow your mind, it’s worthwhile to hear anything Sly was doing at this turbulent time in his life.

If There’s a Riot Goin’ On became Sly & the Family Stone’s last great LP, it would have made sense. The bandleader’s life was in shambles; his drug abuse just kept getting worse, and he consistently failed to show up for gigs. Drummer Greg Errico left the group in 1971, and Sly lost his biggest musical asset when he fired bass legend Larry Graham in 1972. By all accounts, Fresh (1973) should have been the album that proved Sly Stone had lost a step. Instead, it’s his best. From the quirky guitar and punchy horns of “In Time” to the sizzling, gospel-tinged “Babies Makin’ Babies,” Fresh captures Sly at his songwriting peak. It’s every bit as ambitious as Riot and more focused, featuring some of the most imaginative, exquisitely arranged horn parts in the history of R&B.

Also, it doesn’t hurt that the clouds had slightly parted after Riot’s emotional storm. Tracks like “Thankful ’n’ Thoughtful,” “Let Me Have It All” and the spine-tingling “Skin I’m In” wrestle with spiritual identity issues, but possess strong themes of hope and redemption. Fresh isn’t the frenzied sensation that Riot was, but these small glimpses at the sunny side of life make it the deepest record Sly & the Family Stone ever made. Where Riot was frustrated and electric, Fresh is calmer and bittersweet, especially on Sly’s rendition of “Que Sera, Sera.” He sings Doris Day’s defeatist anthem like he’s in front of a sweaty, restless congregation, belting out the chorus over a trembling gospel organ.

The cover may have seemed like an odd choice at the time, but looking back, it perfectly encapsulates the mental state of a tired, tortured genius. It also became his farewell theme, because Fresh would be the last truly brilliant thing Sly Stone laid to tape. The remastered edition, besides sounding impeccable, includes some interesting alternate mixes, including “Let Me Have It All” sans backing vocal, and a horn-less “Skin I’m In.”

Epic/Legacy has also remastered Sly’s 1974 album Small Talk, with four previously unreleased bonus tracks, including an alternate take of the mild hit “Time for Livin’.” Although it’s a look at the “softer side of Sly,” which I doubt anyone was clamoring for, Small Talk isn’t a bad record—when he’s writing the songs, there’s always bound to be something salvageable. The break from “Loose Booty” was a goldmine for Native Tongues-era hip-hop, for example. Still, it’s 11 tracks of light funk and R&B, a sure sign that it’s all downhill from here.

When ranking the most influential artists of the 20th century, Sylvester Stewart has to be somewhere near the top. He certainly passes the “often imitated, never matched” test, and many of his imitators are amazing: George Clinton and Prince come to mind. His influence on hip-hop is immeasurable; listing all the times he’s been sampled would require another article. Oh, and remember how Lenny Kravitz wanted to be him sooo bad? That was funny.

It’s important that Sly go down in history as a unique, galvanizing force, both culturally and artistically, and the Grammys certainly won’t stop that from happening. But that’s not what really matters. When you get down to brass tacks, Sly & the Family Stone is the greatest party band of all time—even when the party started getting ugly.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n15: Open House (4/12/07) > Remastered on the Sly: Sly and the Family Stone: Remastered Editions This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue