Next story: Free Will Astrology

Stumped

by Buck Quigley

Up to 90 percent of the city’s trees sustained damage during last October’s freak snowstorm—officially known as Lake Storm Aphid—which dumped snow weighing nearly 10 pounds per square foot over much of the region. The trees were still covered with bright, green leaves that caught the weight of the snow and later were crushed underfoot as pedestrians climbed over downed limbs that blocked roads to vehicular traffic. The green slush in the road was another strange component to the storm’s immediate aftermath.

Now eight months have passed and the damaged trees have had a chance to bounce back and display their leaves again—just in time to be cut down.

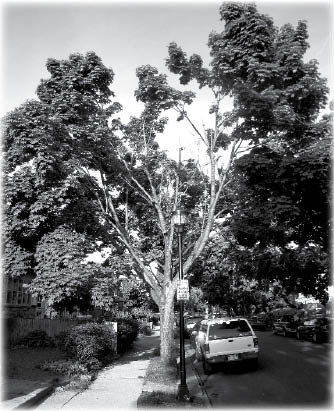

On the morning of Monday, May 21, tree-cutting crews from an Ohio-based company called Arborturf began moving through my neighborhood. They were making quick work of many mature trees that had been put on a list for removal by the city as a result of damage sustained during the weird snowstorm. The 50-foot tall Norway maple in front of my house was on the list, having dropped a big limb that broke the glass of the streetlight next to it and came to rest gently cradling my neighbor’s van. No damage to the vehicle. This spring the tree exploded in vivid green despite the gap left by the missing branches.

On a neighboring street I struck up a conversation with one of the tree-men who had set down his chainsaw for a rest. He told me he was from the South, and that he’d been in this line of work, moving around the country from disaster to disaster, for nearly 10 years. He shook his head and said he had “no idea why all these trees are coming down.”

It was as if the executioner himself was reluctant to perform his task. It wasn’t a real good opinion to share with someone who was about to have the only tree on his property removed.

Let me clarify—“our” tree is not on our property. It grows up from the thin strip of grass between the sidewalk in front of our house and the curb. City property. But having owned the house for eight years, and having raked a lot of leaves, and having worked and played in the shade of the tree with my family on many pleasant afternoons, I’ve grown fond of it. I’m not one of these people you read about in the Buffalo News or see on the local television news stations who’s thrilled to have his or her tree cut down. My wife and I had both called City Hall to request that the tree be trimmed on several occasions over the years. We couldn’t hire a company to come in and do the work privately, or so we thought, because we didn’t own the tree. Ultimately that was a moot point, because the city never sent anyone.

With a ladder and a saw on an extension rod I trimmed a few branches that I could reach now and then, but nothing resembling the kind of tree care a big maple like ours should receive. The night of the storm I went out on three separate occasions with a 10-foot stick and thrust it up into the bending limbs to shake off as much snow as I could. Hundreds of pounds of snow fell. Finally, after midnight, it became clear that I couldn’t keep up. All around me branches were falling from neighboring trees and our street was already clogged with limbs and impassible to vehicles.

The Southern tree-man’s opinion was enough to make me more curious, so I came in to work and made a few phone calls. I left messages with a number of people. I would have called the city’s forestry division, but such a group no longer exists. So I called the Mayor’s Hotline and spoke to Robert Kreutinger, who sent me to Dan Kreuz, interim Public Works Commissioner. I left a message with Kreuz and Dale Kruschke, the City Monitor Supervisor for the tree-removal project.

In the late afternoon on Monday, our tree was still standing. My wife spoke with a guy from Arborturf who came down and gave her his opinion on our tree. She gave me his phone number and I gave him a call. He told me the tree was split and that if it were not cut down it would fall on someone or someone’s car. He admitted he was not a licensed arborist in New York State and I asked him if he could have Dale Kruschke give me a call if he happened to see him. He agreed to, and asked me for a phone number. When I gave him the number here at Artvoice there was a very long pause.

I was then told I had no right to mention in print anything we had discussed. I could not use the name of his company, Arborturf, or refer to him in any story I might write. (We’ll call this employee Tim McNamara, because that happens to be his real name.) We went back and forth for 10 minutes while he demanded I agree not to write anything based on his statements and asked to speak to my boss. I asked him to have Dale call me and told him I’d see him on Tuesday, when he’d told my wife our tree would be coming down.

Shortly after my conversation with McNamara, I received a phone call from Dale Kruschke, an engineer who has been hired by Wendell-Duchscherer, the architecture and engineering firm hired by the city of Buffalo in 2005 as consultants to fill the void left when the city cut its forestry department. Kruschke told me that 4,100 trees were on the list to be taken down in the city this summer, and that nearly all of the trees had been designated for removal by Jeff Brett, the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy arborist who was paid with FEMA funds to diagnose the trees. (Kruschke said 4,100; others said just under 4,000.)

This is important because in order to collect the $1.3 million in FEMA funds for the removal of thousands of trees this summer, the order had to come from someone designated as a New York State Certified Arborist. Brett holds the basic certification offered from the International Association of Arborculture.

Kruschke also urged me to speak with his boss at Wendell-Duchscherer, Art Traver. I called Traver and told him about the situation with my tree. We spoke for a long time and set up an appointment to meet for an interview on Thursday, May 24. During our conversation he said that he believed there were instances where citizens had paid for maintenance to trees like mine and were subsequently reimbursed by the city.

That little piece of information nicked me. Had I known, I would have been one of those people. I gladly would have called in an arborist to fix my tree after the storm had I known there was precedent. A friend of ours who’d worked as a tree-trimmer for years—including with the Olmsted Conservancy—had stopped by over the winter and was of the opinion that the tree could be trimmed and the split could be reinforced with the use of a cable.

On Tuesday, I waited around for Arborturf to show up on my street. They never did. I walked around the neighborhood and saw a small group of people watching crews removing other trees. One resident pointed to an enormous maple on her property that had been struck by lightning a while back, unrelated to the October storm. The damage had been severe, but she pointed up to the huge bolts that had been driven through the trunk of the tree and had held it together as it healed. I asked who had done the repairs and she referred me to Greg Haskell, owner of Haskell Tree Service and a licensed arborist since 1973. “He’s not cheap, but he’s very good,” she said.

The confrontation

By Wednesday morning, I didn’t know whether Arborturf would be coming for my tree or not, having failed to show up on Tuesday when we’d been told to expect its removal. I asked a neighbor to keep an eye out and asked for a phone call if the cutting crews arrived.

Sure enough, just after nine o’clock that morning I received a call that the crew had just pulled onto our street and were beginning to dismantle another tree. I grabbed a video camera and made a quick call to Greg Haskell. I reached him, introduced myself and explained the situation. He told me that he’d been in disagreement with the way the city was handling the process, and that he would come out and do an assessment of our tree. In his estimation, 90 percent of the trees being brought down would survive if they received proper attention. I’d have to call back to make an appointment, he told me, but he would come and have a look.

I pulled onto my street and parked in front of my house. I pulled out my camera and got on my cell phone. I left a message with Art Traver. I left a message with Dale Kruschke and Dan Kreuz. An Arborturf foreman named Terry showed up and I began explaining that I was trying to appeal the tree’s removal. I was asking for a stay of execution, in other words. Too many issues had come to my attention to simply let the tree come down without further appeal.

Among my concerns was the fact that there was no plan in place to remove the stump that would be left behind when Arborturf pulled away. The letter we’d received from the city indicated that we could request a replacement tree and that the city plants trees in the fall or in the spring. There was no specification as to the year in which we might receive our replacement tree, and when asked, no one could pin down exactly when that might be.

Stories in the media have suggested that FEMA would step up to the plate and provide the money to remove the stumps, but I’d learned from Art Traver that in fact FEMA has never paid for such an operation. It would be unprecedented and very unlikely for them to do so. And you can’t plant a new tree where a stump remains. Not to mention an extensive root system.

I explained that to Dan Kreuz when I finally reached him at City Hall. He said that there was a “plan B” in place should FEMA not come through, but when I asked if he could fax me a copy of that plan he admitted that it hadn’t been written yet. There was $1,000,000 earmarked in this year’s city budget to hire a city forester to trim and plant trees as well as remove stumps, he told me, but that allocation hadn’t yet been approved.

In the meantime, Terry asked me to move my car so he could get to my tree. I refused. He said he was calling the police to have it towed. Comically, in the middle of all this, I received a call from Art Traver informing me that he was no longer allowed to speak with me and would have to cancel our interview on Thursday, per Dan Kreuz, with whom I had only just finished speaking.

Dale Kruschke then showed up, as well as the former city forester, Ed Drabek. How Drabek happened to show up, I have no idea. But it was nice meeting him, and he told me that he reads Artvoice.

Finally it was determined among Terry and Dale and numerous phone calls that if Dan Kreuz would agree to allow me a second opinion on the tree, it could be saved for now. I begged Kreuz for the opportunity, pointing out all of the concerns that had come to my attention over the previous three days. Kreuz finally relented. My tree could stand until an independent arborist could have a look. I handed my cell phone to Terry, who began to tell Kreuz that the tree had to come down. Then he listened for a minute and handed the phone back to me.

I thanked Kreuz for the opportunity and thought I was out of the woods for the time being, when Terry told his guys to pull up the truck because the tree was coming down. I protested and handed the phone back to him. After a brief conversation with Kreuz, Terry said, “Yes, sir. I understand.” He handed the phone back to me, and Dale Kruschke removed the sign from the tree trunk that had marked it for removal. The crew left the street, but Terry sat in his truck for another 45 minutes, lurking. So I left my car under the tree and waited, anticipating another miscommunication that would send the guys up in a bucket with chain saws. He finally left, and I went back to the office.

The second opinion

The earliest appointment I could get with Haskell Tree Service was for the afternoon of June 6—two weeks after our tree was to have come down. That was plenty of time to think about what had occurred. I went back and forth wondering if I’d done the right thing by arguing to save a tree that in the final analysis did not belong to me. In the end I had to remind myself that I wasn’t claiming to be an expert. At least this way I could feel I’d done everything I could to maintain the big tree that has stood in front of our house since long before we bought it. I wondered how much hotter our house would get in the summertime, left to bake on the sunny side of the street. I worried for the front yard garden my wife had been working on over the years, full of plants that thrive in the shade. We’d been holding off on planting new grass because we didn’t know whether to buy a variety that grows well in the sun or in the shade. Privately, I prepared myself to be told by Haskell that the tree was a goner.

The day arrived and I went to meet Haskell. He pulled up and began inspecting the tree.

“The tree can be saved,” he said. “Broken limbs should come out, cut to a lateral branch. There’s a very bad scaffold crotch here. A cable should be installed to keep the tree from splitting. What may have to be done is the right-hand side of the tree might have to be lightened a little bit to assist the holding power of the cable. Nutrients should be provided for the tree—if the city can’t do it, the tree should survive regardless.” (A complete video version of Haskell’s assessment can be seen at Artvoice.com.)

He wrote up an estimate to do the repairs, but reminded me that he would need written permission from the city before he could do anything to save the tree.

Haskell has been critical of plans that advocate cutting down storm-damaged trees throughout the region. He maintains that the costs associated with tending to damaged trees and bringing them back to health is significantly cheaper than chopping them down, removing stumps and roots and replanting with a new, young tree.

The problem is that his view doesn’t line up with the operation that is unfolding in Buffalo this summer.

If you have tree-related questions in the City of Buffalo, here is a list of helpful phone numbers:

Dan Kreuz, Interim Commissioner of Public Works 851-5636

Art Traver, Wendell-Duchsherer, Architects & Engineers 688-0766

Rosanne Lettieri, President, Dreamco Development Corp 896-6344

Jeff Brett, Tree Care Supervisor, Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy 838-1249 ext *822

Dale Kruschke, City Monitor, Wendell-Duchscherer 982-3369

Mayor's Hotline 851-4890

Haskell Tree Service, Inc 655-3359

Take the money and run

The cash-strapped city is in a difficult position. Without a forestry division when the storm hit, the city’s overall line of thinking seems to be this: FEMA will reimburse us for the $1.3 million we are paying to companies like Arborturf, but that window is only open until October 2007. After that, we’ll be back on our own to care for our trees, so why not get rid of every one that might need further attention down the line? It has been widely explained to me by people involved in the removal that FEMA sets the rules, and they will not pay for things like corrective pruning. They’ll only pay to take a tree down to its stump.

However, FEMA External Affairs Specialist Barbara Lynch told me that the individual municipalities decide such guidelines and referred me to North Tonawanda as an example. I spoke with Gary Franklin in North Tonawanda’s Department of Public Works, who said his department opted to have their trees pruned branch by branch, with FEMA reimbursement to pay for the work. They completed work on their damaged trees last December. The hired contractor brought down limbs that were clearly snapped, but whenever possible left the tree standing. Franklin said he was pleased to have avoided large-scale tree removal and seemed proud of the fact that so many of the trees have bounced back. He also said they have no liability concerns over the trees that remain, although they are now embroiled in appeals to FEMA to get the money due them.

The $1.3 million Buffalo’s control board approved to be spent on the current tree-removal project is indeed a lot of money, and it’s imperative that when all is said and done FEMA comes through with reimbursement. So who was actually in charge of contracting with the various tree services to come to town and remove the trees? Art Traver at Wendell-Duchscherer directed me to a company called Dreamco Development Corporation. He gave me a phone number for Rosanne Lettieri, the company’s president.

Last Friday I gave Lettieri a call. The receptionist answered “DiPizio Construction Company.” I told her I must be mistaken, I was trying to reach Dreamco. She said I’d called the right place but that Rosanne was not in. I told her who I was and asked if she could give me a call.

Curious, I did a Google search and found that Dreamco Development does not have a Web site. What did turn up was a series of search results indicating that Dreamco has been a significant contributor to a number of politicians over the last several years—notably Congressman Tom Reynolds, who took credit for securing federal disaster funds for the region after the October storm, perfectly timed with his then foundering re-election bid last fall, which sagged under the strain of his role in the Capitol page scandal involving Mark Foley.

Dreamco Development is also notable for its involvement in a controversial arrangement made in the late 1990s with the city of Buffalo wherein they purchased a firehouse and then leased it back to the city. In 2005 the power at the firehouse was turned off for three hours because of an unpaid utility bill.

On Monday, I went to the Cheektowaga address I’d been given for Dreamco. The receptionist remembered my phone call, but told me that the best way to reach Rosanne was to set up an appointment. She told me she’d given her the message from Friday, but I left my card as a reminder and asked her again if she could have her give me a call. The receptionist told me there was nobody else there from Dreamco, and that everything pertaining to the company went through Rosanne.

When I got back to the office, Artvoice editor Geoff Kelly informed me that Rosanne Lettieri happens to be the sister-in-law of County Executive Joel Giambra. She still has not responded to me.

The Lorax

When my daughter was very little, we sat in the front yard reading The Lorax by Dr. Seuss. The Lorax, you may recall, is an odd little character that “speaks for the trees.” It’s a little parable about the greedy Once-ler who cut down all the Truffula trees to make garments called Thneeds from the tree’s bushy tufts. Against the pleas from the Lorax, Once-ler succeeds in destroying the entire forest, leaving only stumps. Then he couldn’t make any more Thneeds. The story ends when Once-ler, finally aware that he’d been foolishly driven by greed, gives the last remaining Truffula seed to a young boy and instructs him to grow it and protect it from axes until it can grow into a new forest.

I was acting on a simple impulse when I decided to appeal the removal of the tree in front of my house. The more questions I’ve asked about the whole process, the more resistance I’ve met. There’s more information out there, like how much the city pays Wendell-Duchscherer to perform the role an actual city forester would perform, but I’ve been made to file a FOIL request to get such sensitive data, even though it clearly should be public information.

Along the way, when every other argument has failed them, those who’d like to take our tree down have said that it will be a safety hazard if left standing. Each time I’ve referred them to a towering dead tree that stands six doors down from me. If public safety were the primary concern, that tree would have been removed a long time ago. The tree has been dead for several years and the property owner long ago requested its removal. It’s been on an official list for removal since May 26, 2006—five months prior to the October storm. That tree still stands because, as one Arborturf employee told my wife: “If FEMA won’t pay for it, it isn’t dangerous.”

Since Greg Haskell’s assessment, Olmsted Parks arborist Jeff Brett has sent me an email that concluded: “If you or the City wants to invest in having your tree braced and cabled, I would retract my recommendation to have it removed.”

So there we are. It’s a matter of a few hundred dollars for the repairs. For my part, I know what I’d do if the tree were really mine.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n24: Stumped (6/14/07) > Stumped This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue