Bad Metaphors, Bad Government

by Bruce Jackson

Silver bullets

In Buffalo, as in many cities, politicians and developers are always talking about the “silver bullet.” Usually the politicians and developers are rhetorically putting it in the negative, saying that they aren’t claiming the project they are presently trying to justify or get the populace to buy into is the silver bullet that will save the city, after which they go on to explain how this project will save the city if only the populace will buy into it.

Seneca gambling bosses Barry E. Snyder Sr. and E. Brian Hansberry, for example, recently wrote in a Buffalo News “Another Voice” essay that “The Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino alone will not be the ‘silver bullet’ to keep our young people from leaving New York and bring back those friends and family members who have already left the area.”

If it won’t be it “alone,” that means they claim it will be the silver bullet that, in collaboration with something else, will achieve those ends. They’re doing their share to develop Buffalo by developing this wonderful partial-silver-bullet casino. They’re doing what they can to keep kids from leaving and to get the departed to come back.

You and I know, as they do, that the only thing driving them to develop this casino in downtown Buffalo is the money they can take out of downtown Buffalo. All the rest is silly-putty and puffery, which the Buffalo News, for some reason, obligingly published for free at the bottom of its editorial column rather than charging them the usual advertising rates.

Language scholars call that device—saying you’re not going to do something, then immediately doing it—“rhetorical disavowal.” It’s what Shakespeare’s Marc Antony does at Julius Caesar’s funeral when he says “I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him,” after which he goes on to praise Caesar so well that everyone listening is driven quite crazy, which is just what Marc Antony intended.

Politicians and developers don’t like to be caught claiming their latest project is a “silver bullet” because opposition groups jump all over them with reminders of all the past “silver bullets” that failed to find their mark and just turned out to have been disasters that destroyed quality of life and were a huge waste of money for everyone except the lobbied politicians who were paid for their service and the developers and the other hustlers who made quick bucks during the construction phase and then turned their attention to something more rewarding.

Like, for example, Buffalo’s Kensington Expressway, which presumably was built so more people from the suburbs could get to Buffalo faster and easier and would thereby energize downtown, but which had exactly the opposite effect: It hastened the decline of downtown Buffalo, slashed through vibrant neighborhoods, and helped shift the city’s population to the suburbs.

Or, looking forward, the Bass Pro project at the Erie Canal Commercial Slip, which will happen at the cost of a carefully worked out waterfront development plan and which will drop on a key piece of newly prime waterfront property a big-box sporting goods store and two huge, bland, above-ground parking lots, most of it underwritten by taxpayer dollars.

Or the Seneca Buffalo Creek Casino, which Buffalo Mayor Byron Brown is panting after, which has the promise of sucking out of town 10 times as much money as it leaves behind and, in the process, displacing more current jobs than it will create.

Even if it were a silver bullet

it wouldn’t be a silver bullet

Even if what the proponents of Bass Pro and Seneca Niagara are promising had the faintest chance of coming about, which is unlikely for Bass Pro and impossible for Seneca Niagara, “silver bullet” is the wrong metaphor. These hypesters in City Hall and elsewhere should at least get their language straight.

“Silver bullets” aren’t cures. Silver bullets either deliver death or denote anachronistic romantic melodramas.

The death part has to do with werewolves, those humans who at the full of the moon purportedly grow huge clumps of body hair and fangs and run around on all fours killing people. It is said by people who claim to know about such things that the only way to kill a werewolf is with a silver bullet. (Vampires, I’ve heard, are also vulnerable to silver bullets; however, the more common practice for dispatching them is a wooden stake in the heart.)

But, so far as I have been able to determine, there are no werewolves in Buffalo. There are some swine, some snakes, some rats, but no werewolves. Which means that the bullet that will kill the otherwise unkillable hairy fanged quadruped will not solve any of Buffalo’s pressing problems.

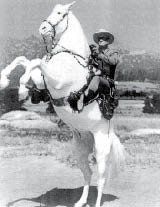

The other silver bullets—and the ones I think that lodge deeper in the popular imagination—are the bullets that the long-time radio and television Western hero, the Lone Ranger, loaded in his silver pistols and sported on his pistol belt. He owned a silver mine and was a silver freak. His horse was named “Silver.” He had a silver belt-buckle. He wore silver spurs. He went around the West with his “faithful Indian companion Tonto” seeking out evildoers. When he found them, they would usually pull their guns, at which point he not only outdrew them but he invariably shot their pistols from their hands with his twin silver six-guns and his silver bullets. Then he quickly rode away because, as the late comedian Lenny Bruce noted, he didn’t want to get hooked on people saying, “Thank you, masked man.” As he rode off someone would say, “Hey, there’s a silver bullet on the table.” And then that person, or perhaps another, would say, “Who was that masked man?” Whereupon we’d hear, slightly off mike, the cry, “Hi-yo, Silver, away!”

The Lone Ranger never killed anybody. All he did was shoot malefactors’ guns out of their hands or shoot holes in the hands holding guns. Holes in the hands, in the radio and TV series, were always depicted as annoying wounds, momentarily distracting like splinters, rather than the permanently crippling wounds they in fact are. A .45 caliber bullet blowing out the hand’s metacarpals and phalanges does damage that never heals, but that never figured in the Lone Ranger narratives. In those narratives, the silver bullets stopped dangerous guys from being dangerous, but never damaged anything or anyone beyond the point of “Ouch!” or “Oof!”

Silver bullets never created anything. They never fixed anything. They never related to any economy anywhere. All they ever did was remove pistols from malefactors’ hands in a romantic radio-TV series about an old West that never existed or kill werewolves, an affliction which, as I noted above, is not of significant concern in modern-day Buffalo.

Get the right bullet

What the politicians, developers and their opponents are really talking about when they claim or denounce a “silver bullet” solution is far closer to a “magic bullet” solution.

The phrase “magic bullet” enters American popular culture in 1940, with the film of that title, starring Edward G. Robinson as Dr. Paul Ehrlich, the Nobel Prize-winning German physician, who developed a way of marking the tuberculosis bacterium, an important step in diagnosing the disease. He went from there to seek “magic bullets” that could be injected into the blood that would target specific diseases.

Ehrlich’s primary achievement in that area was a cure for syphilis, which he named “606” because it was his 606th experimental attempt. The drug he used was an arsenic compound. Ehrlich’s idea was right—it was possible to target a specific disease with a specific medicine—but 606 was a little too vigorous for the patients getting it. It killed 38 of them. Eventually, scientists found a cure that wasn’t as deadly as the disease and nowadays nobody with a decent medical plan has to have syphilis more than a week after the blood test, but in the moment, for those 38 patients taking the cure, Dr. Ehrlich’s magic bullet was pure poison.

The lesson is, you have to be very careful when you fire off what you hope will be a magic bullet, because sometimes the bullet does more harm than good.

Getting screwed

The politicians and developers saying or implying that they’ve got the silver bullet that will cure the city’s ills (“The Kensington will revitalize downtown!” “The casino will bring in more money than it takes away!” “Bass Pro will jumpstart the waterfront!”) are like the teenage boy begging the teenage girl to do it with him not because he is insanely horny but because he is truly in love, or the used car salesman swearing he wouldn’t lie to you just to get you to buy that car, but rather because he knows this is indeed the perfect car for you.

The politicians, developers, horny teenagers and sincere car salesmen may really believe what they’re saying at the moment they are saying it. But if you buy their pitch, the results are the same, whether it’s the politician, the developer, the horny teenager or the used car salesman you’re listening to: They get what they want and you get screwed.

Maybe the next time Byron Brown or Barry Snyder or any other politician or developer or casino operator does the “Aw, shucks” routine telling you his latest project isn’t a silver bullet when that is exactly what he’s hoping you’ll be sucker enough to believe, you should tell him he’s got his metaphors wrong. Tell him you don’t have syphilis and you don’t want his arsenic. Tell him that you’ve had quite enough of lousy government, lousy prose and “development” projects that leave us with less than we had before. Tell him that what you demand now is competent planning and competent, responsible leadership. Tell him you deserve it, your kids deserve it and the city deserves it. After all, you’re the one who’s paying for it.

Bruce Jackson’s latest book, The Story is True: The Art and Meaning of Telling Stories, was published last month by Temple University Press.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v6n31: Fall from Grace (8/2/07) > Bad Metaphors, Bad Government This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue