Next story: Three Guys Walk Into a Bar... Nor-Tel Grill

Where Are the Beers of Yesteryear?

by Buck Quigley

With Flying Bison in limbo, a look back at Buffalo brewing history serves as a lesson to the would-be brewers of today

Buffalo got an unexpected boost in 2007 when Labatt USA moved its headquarters to Key Bank Tower. Although city officials didn’t know of the move until it was announced, Mayor Byron Brown was there at the grand opening. He took the opportunity to step behind the bar to pose for the cameras and say a few words.

Labatt is one of those Canadian brands that folks in our northern border town have adopted as our own. Over 40 million bottles of Labatt’s beer is sold annually in Erie and Niagara counties alone. The headquarters employs a couple dozen people in sales and marketing, and it seems miraculous when any company arrives here without the lure of generous tax incentives.

Still, it’s interesting to look back at what became of an industry that grew and flourished right along with the city’s own impressive growth in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Buffalo’s beer-drinking history is as old as the city itself, and even older, when you consider that in 1824 the village of Buffalo boasted two breweries but only one bank. The first hospital wouldn’t open for another 24 years. Today it’s hard to imagine what it must have been like when this industry was in its heyday, employing thousands locally, and selling its product to a thirsty local population.

Just blocks away from Key Bank Tower, at the corner of Virginia and Washington, you can still see the façade of the Ziegele Brewing Company’s Phoenix Brewery—so named because it was rebuilt from the ashes of Ziegele’s first brewery, which burned twice at the corner of Virginia and Main. A fragment of this past is still going strong at Ulrich’s Tavern, Buffalo’s oldest continually operating bar, at the corner of Virginia and Ellicott. Located directly behind the brewery, Ulrich’s would have sold Ziegele’s lager, or “strong beer” as it was then called, when the brewery employed 80 men and cranked out 80,000 barrels (about 2.5 million gallons) of beer, in 1888.

Ziegele’s wasn’t the only hometown brewery then, nor was it the largest. There were more than 38 such businesses. The largest during the pre-Prohibition era was the Gerhard Lang Brewery, which produced 300,000 barrels annually on the 34-acre site where Lang’s ornate “Palace Brewery” stood—the largest in the state outside of Brooklyn. The brewery employed 110 men in 1887, and distributed beer directly to Philadelphia and New York City in refrigerated rail cars. The opulent Annie Lang Miller house at 175 Nottingham Terrace was built for Gerhard’s daughter.

Few people realize that there is no major brewery that’s independently owned in the US today. Most people are surprised to learn that our global marketplace now means that American mega-brewers Miller and Coors (and Canada’s Molson) are owned by South African Breweries, Ltd., while red, white, and blue brands like Budweiser—and even local Canadian favorite Labatt—are owned by Anheuser-Busch InBev, a Belgian concern. (Although the US Department of Justice required InBev to license out Labatt USA last year in an effort to keep prices down in Upstate New York, where Anheuser-Busch and Labatt are the two biggest-selling brands. Labatt USA is now controlled by KPS Capital Partners.)

In some sense, beer, the drink of the American workingman, seems to have suffered a fate similar to the fate of American workers themselves. Outsourced and sold out. But for the moment, let’s raise a glass to a time when people worked, earned, bought, and played more locally.

My bucket’s got a hole in it

Historian and filmmaker Stephen Powell is the author of Rushing the Growler: A History of Brewing in Buffalo. His book is recognized as the bible to local enthusiasts of this rich heritage. The “growler” referred to in the title is a metal pail that was used to transport beer in the days before bottling. Spry young boys would hang out by factories in the city waiting for the noontime whistle to blow, and as workers spilled out for lunch the runners would be sent to fetch buckets of beer from nearby saloons for the men to enjoy before they had to return to work. Time was of the essence. Hence, “rushing the growler.”

Powell describes how alcohol was traded with Indians for fur as far back as the 17th century. As settlements developed and crops were grown, brewing followed close behind. Taverns were the first public buildings in most towns, providing a place to eat and rest for travelers. In short order, it made sense for tavern keepers to expand their beverage list, and brewing became an essential part of the operation. Much of the business took place on a barter basis, with grain often being traded for a taste of the finished product. This was the general model until the middle of the 19th century, when larger breweries began forming alliances and co-ops to expand their distribution and buying power.

It was during this time that saloons could be found on virtually every corner in the city. Individual breweries owned most of these, and each one acted as an exclusive distribution point for each brand.

In Buffalo, breweries like Ziegele’s, Gerhard Lang’s, Magnus Beck’s, the German-American Brewing Company, and William Simon’s, to name but a few, were collectively cranking out hundreds of thousands of barrels annually, but they paled in comparison to Milwaukee-based Pabst and Schlitz, who had passed the million-barrel mark. Thanks to expansive railroad distribution networks, these Midwestern giants were the first of the mega-brewers. They created a new business model built on massive distribution and big advertising that would increasingly put the squeeze on regional brewers right up until 1920, when Prohibition put a crimp in everyone’s style.

During Prohibition, many breweries closed while others went into the production of soft drinks, malt health tonics, dairy products, or whatever else they could make in their large factories. Many continued to make beer illegally, hoping that inspectors would skip over the vessels containing the contraband. Thanks to its proximity to Canada, where liquor was still legal, bootlegging was common and speakeasies were plentiful. Still, the noble experiment ended a way of life for many.

Happy days are here again

After 13 years of Prohibition, breweries in town started up again, but the game had changed. New taxes were a burden for New York brewers, and a new Beer Control Board (BCB) kept a close watch on the goings-on at saloons. Further, bootleggers, or “wildcat” brewers, had become skilled over the past decade, making it more difficult for legitimate businesses to compete.

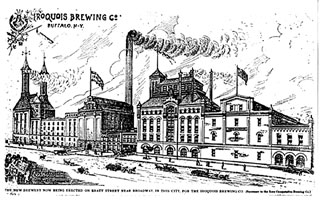

In addition, the Midwestern mega-brewers were firing up their boilers and pumping out the thin, bubbly, pasteurized stuff that has come to symbolize American beer today. Only the strongest local breweries were able to survive, but only for a time. Here’s a list of the larger ones who flared out: Gerhard Lang Brewery in 1949 after 107 years, Magnus Beck in 1955 after 115 years, Phoenix Brewery in 1959 after 90 years, Broadway Brewing Co. in 1959 after 107 years, Iroquois Brewing Co. in 1971 after 141 years, and Simon Pure in 1972 after 113 years.

Everything old is new again

When the Buffalo Brewpub opened on Main near Transit in 1986, it was the first such establishment in the state. The Breckenridge Brew Pub had a short heyday downtown before closing, and one can still order a selection of beers brewed on-premises at the Pearl Street Grill & Brewery.

The microbrewery trend that we’re experiencing today is not so different from the early taverns that sprung up on the Niagara Frontier as settlers moved west. One big difference and problem is the lack of good public transportation in our area, making a trip from a watering hole in a car a dangerous and potentially illegal proposition. Such was not the case in the golden era of the saloon, when streetcars moved people efficiently regardless of their state of sobriety.

A unique case is that of Tim Herzog’s Flying Bison Brewery, the first stand-alone brewing operation to make a go of it in the city since 1972. Flying Bison sold their first beer in May, 2000. Originally, they intended to go the way of the brew pub, operating as a restaurant that sold its own beer. Instead, they realized that none of the original partners had any experience running a restaurant. In addition, they realized that instead of competing with the more than 700 restaurants in the area, it might be better to try to service them.

“We liked those odds better,” Herzog explains.

The pink elephant in the room remained the mega-brewers. “Labatt’s is the big one. You can never discount Budweiser. But Genny and Labatt are the closest breweries to the city, so they really were the hometown beer,” Herzog says. “They have great distribution and people like those brands. You can’t beat that. Labatt’s has done a tremendous job marketing in this area with Thursday in the Square, pond hockey, the Buffalo Bills—those events where people do go out and drink beer. They’ve hiked the price of poker to be sure, in sponsoring those events, because the small independent can’t do that.”

Herzog likens what’s going on now with global consolidation of beer companies to what went on in the 1950s, only on a higher level. “It was Schlitz, Pabst, Schmidt’s, those kinds of brands that got absorbed.”

“Matt Brewery, New Belgium, Sierra Nevada, Sam Adams—it’s really the craft brewers that are independently owned American companies today. While Budweiser would like to be as all-American as stock car racing, it’s now a Brazilian guy who runs a Belgian-owned investment group who owns and runs breweries and other drink businesses.”

How have things changed from his point of view? “When we started, there were five distributors that serviced Erie County. Now there are two. The consolidation in the beer business has been tremendous over time.”

Fortunately, in New York State, you can self-distribute. In some states you can’t even do that, which makes the idea of a startup impossible.

Flying Bison has done its share of sponsoring lots of smaller local events that rest under the radar of the mega-brewers. Word of mouth has done a lot to promote the product in town. Still, after 10 years building customers, at present the brewery is not producing beer. Herzog sounds optimistic when he talks about a prospective arrangement with Matt Brewery that would allow Flying Bison to fire up the factory and start making beer in Buffalo again. The big problem has been keeping up with the cost of materials. Hops, one of the most important ingredients in making beer, is prone to wild price swings that are easily negotiated by mega-brewers, but not so by the little guy.

Ironically, New York State once led the nation in hops production. Only now is it being looked at as a legitimate cash crop again, after losing ground to the Pacific Northwest. Last summer, farmers in Central and Western New York started growing it commercially again after a 50-year hiatus.

For his part, historian Steve Powell thinks it’s possible for a local brewery to make it again. “Buffalo is viable place to become a brewer,” he says. “It would take loads and loads of marketing, which would require a marketing budget. That marketing is probably more important than the beer you make. And distribution. It boils down to that. A lot of people can make a good beer. You have to decide if you’re going to make a good beer or not. Then it’s down to how much can you push it, create a brand, and get it out to your customers. That’s it.”

|

Stories Behind Famous Local Watering Holes Shaken Not Stirred • Steaking our Reputation Food For Thought • Boozy Playlist |

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n10 (The Drinking Issue: Thursday, March 11) > Where Are the Beers of Yesteryear? This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue