Next story: City of Magic, City of Light

More Than That

by Thomas Dooney

Karen Finley brings The Jackie Look to Hallwalls

Bring up the name Karen Finley in conversation.

Someone nearby is bound to bring up the “grocery list”…that dubious inventory of objects Finley has used, or is alleged to have used, as erotic props on stage. Yams. Honey. Canned beans. Bean sprouts. And of course, all that chocolate syrup.

Sometimes the public only comprehends an artist’s methods as a bag of tricks. Then these gimmicks become more discussable than the artist’s accomplishment. Finley is not alone in this. Picasso has been in public consideration for more than a hundred years and still people focus on noses where eyes should be and ears somewhere else.

It’s easy to imagine becoming tired having to counter criticism which diminishes complex work to a stunt. In a phone interview, Finley explains there is more to that audience response. She reasons, “Something interests me in the psychology of the viewer. They look at work and want it to remain just as they remember it. There is a desire to maintain a past that they imagine.” People prefer their own recall rather than reality, she conjectures, as a defense against anxiety triggered by a performance.

Finley meets her audience at these fixed, frozen moments. They, seeking familiarity. She, leading them to another meaning...something more than when the moment is in motion.

Of course, Finley’s solo performances have never been about the food, despite ongoing, reductive appraisals. The shows have provided food for thought on such varying subjects as nature of sex, authority, power, and fame. She explores the abuses of influences as well as their thrall. What is most provocative, or disturbing for some, are her explorations where those matters overlap.

Buffalo audiences may have an advantage over those in other cities. Because she has performed here several times in different shows over the years, Buffalo audiences have been treated to a works that display Finley’s depth, breadth, and development. She returns to Hallwalls this week with her latest show, The Jackie Look.

Bring up the name Jackie and no one has to ask, “Jackie who?”

Finley accepted an invitation from the Society for Photographic Education to be a keynote speaker at its February 2009 conference, held in Dallas. One of the event’s exhibits was to be held at the museum that is housed in the building once known as the Texas Schoolbook Depository. Since 1989, the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza has welcomed visitors seeking information and understanding the events of November 22, 1963.

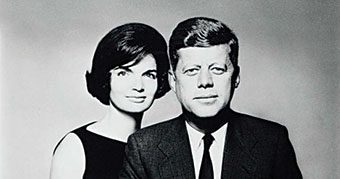

Finley decided to deliver her keynote as Jackie and to docent that exhibit with I-was-there acumen. She soon realized this concept had appeal beyond a one-time presentation. This was confirmed by the response of those at the conference, witnessing an apparition of la Santa Jackie Bouvier de Kennedy y Onassis, a vision only two blocks away from the famous grassy knoll. The lecture evolved into a performance and has continued to take shape as The Jackie Look.

“I am not doing this performance everywhere,” Finley says. “I am being selective where I do this.” Earlier this year, The Jackie Show intrigued audiences off-Broadway and more recently on Kennedy turf in Massachusetts, at the Peabody Essex Museum, in conjunction with a display of Richard Avedon photos called The Kennedys: Portrait of a Family.

Finley’s criteria would seem to be performing in venues with some Jackie association or cities where she relishes the audience, as she does Buffalo. “I like the city,” she says. “I like where it is situated, so close to Niagara Falls. I like the people, how resilient everyone is. Here in this coldest, remote place, and it has a strong arts audience.” Finley has been researching Kennedy connections in Western New York for The Jackie Look.

The phrase “the Jackie Look” was first used to describe the First Lady’s fashion sense. Savvy enough to be admired in European salons. Versatile enough to get through the personal, public, social, and domestic agendas of an American woman’s busy day. The title neatly recalls the actual moment and the Camelot mood, as well as Jackie’s role as Guinevere.

The show’s title also tells us that the evening will be Jackie’s turn: The reticent icon comes forward to tell the stories behind the memorable photos, whether shot by Avedon or Ron Galella, from home movies or the Zapruder film, from LIFE magazine or the National Enquirer. Proof that Jackie has kept up with the times, there is also a PowerPoint visit to the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza.

In addition, the title inherently references a concept fundamental to analysis of visual arts: the gaze. Simply put, the gaze conjectures the relationship between the subject of a portrait and the surrounding world, both artistic and material. Does Mona Lisa see a friend or a lover approaching? Does she see Leonardo? Or is she smiling at you? Here, Jackie tips up her oversized sunglasses to consider her world and ours.

Finley credits Buffalo, and Hallwalls, for helping bring her art to a more serious level of consideration. Finley’s first appearance here in 1982 earned her public and critical attention that she had not yet secured playing downtown clubs in New York City. Her earlier shows were backed by some of the best known DJs on the scene at the time. Rhythm-driven rants layered raw, sexual language upon popular music with heady results. Finley also worked alongside other pioneers of performance art, such as the Kipper Kids and David Wojnarowicz, learning to meld shock and entertainment and meaning.

Moving from a featured act on a bill amongst other acts in a club to the showcase performer in a gallery demands the production of more comprehensive, articulate, and visionary efforts.

In 1990, Karen Finley received a project development award, decided upon by a national panel of peer artists, from the National Endowment of the Arts. Finley was caught off guard in June of that year when her award and those of three others were cancelled by John Frohnmeyer, the agency head and an appointee of President George H. W. Bush. Frohnmeyer’s veto seemed motivated by screeds from the likes of Senator Jesse Helms and Christian conservatives still flustered by the previous year’s furor over Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ and the exhibit of Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center.

Sex clearly was the issue. The other defunded artists (Tim Miller, John Fleck, and Holly Hughes) were gay and created works with explicit, gay content. Finley, the only straight artist in the group, underwent a gantlet usually reserved for gay people. In essence, she had to come out in public, have her sexuality and sexual imagination scrutinized, and then be categorized as a freak.

Together the artists took action. In 1993, they won a case in court on the grounds that their First Amendment rights had been violated and their work censored. They were awarded amounts equal to the grant money they’d lost. This victory was brief. In 1998, the US Supreme Court ruled that NEA standards of excellence and merit did not inherently interfere with any of the artists’ First Amendment rights nor violated constitutional vagueness principles.

An exhausting, costly legal campaign that lasted for most of the 1990s came to naught—and, as a result, NEA has changed its policy and no longer endows individual artists. While Finley and her colleagues may have, in the final count, lost the case, they became heroes of artistic freedom in the decade-long discourse. Still, she is reluctant to concede that any PR is good PR.

“Five days after losing that case I lost a show at the Whitney Museum,” she recalls, rage coloring her voice. “Before, I had performed my work at Lincoln Center. After losing the lawsuit I still do not have the access to major institutions and museums.”

As a result of losing the appeal, she says, “I can still be considered indecent.”

Asked what she lost through that ordeal, she immediately replies, “My privacy.” There is a silence before Finley recounts the time sacrificed when she could have been creating, writing, performing. She treats the lack of continuity at that point in her career as one might a scar.

Finley explains that her work is different now, both the product and the process. “I used to create a show and tour it,” she says. “I no longer tour the hell out of show. I tour less but am more prolific.”

She has created an impressive number of shows during the past 10 years in which she impersonates well known people, some in homage, some less seriously. As Liza Minelli, Finley reported on the destructions of 9/11. As Laura Bush, she litanized erotic dreams. As Martha Stewart, she depicted herself as married to George W. Bush—a contemporary “George and Martha” harkening both the first First Family and the central characters of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? Finley’s most recent appearance at Hallwalls explored the worlds of Eliot Spitzer, Silda Wall Spitzer, and the sex worker known as Ashley Dupré.

These shows, as The Jackie Look does, portray women addressing public adversity and striving for personal renewal.

This week, Finley will don a wig created to give her that Jackie look. She will slip into an Oleg Cassini jacket. She will accessorize with a pair of vintage Gucci sunglasses. She will be the very image of the woman from whom no one could turn their eyes or their cameras. But the show offers more than that. From the vantage point of the pedestal the public erected, and using Jackie’s talent to mesmerize, Finley will detail an inner life.

Through her own ordeals, Finley claims to have made deeply personal gains. “I have gained the joy of making work. I create work that is on the edge because I have not been allowed to be comfortable. But I have been allowed myself to be happy.”

The Jackie Look runs July 14-17, 8pm, at Hallwalls Contemporary Arts Center (341 Delaware Avenue at West Tupper). For tickets and information, visit Hallwalls.org or call 854-1694.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n28 (week of Thursday, July 15) > More Than That This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue