Next story: The Long Walk

That '70s Show...

by J. Tim Raymond

Reflections on Wish You Were Here, the Albright-Knox Art Gallery’s survey of Buffalo’s avant-garde scene in the 1970s

We moved up here to Western New York in January of 1990. My then wife and baby daughter and lived in my mother-in-law’s house while I went to night school for a studio arts degree at Daemen College. During the day I taught art and art history at ECC’s city campus.

Having been visiting artist at University of Texas at Austin for two years since leaving New York City and the spiraling-out-of-control art world of the late 1980s, Buffalo was where I could see myself catching a breath. For surviving artists, the 1980s like the 1920s were a whirl of wheeling, dealing speculation. Corporate art buyers, like great while sharks in suspenders, moved across 57th Street, Soho, and the East Village chewing up and swallowing whole galleries of young artists, keeping few, spitting most back out on the pavement. Investment brokerages built special rooms hermetically sealed and climate-controlled to house the bulk of their patronage, where it coolly sat aging into vintage.

In the 1970s, engendered by a burst of funding at both the national and state level, arts grants had become available for culturally progressive organizations to pursue. Across the country arts organizations and venues lined up for the congressional largesse of momentary liberal persuasions, knowing the funding window could slam shut once the conservative mindset recovered its senses in Washington and Albany.

Meanwhile, those artists who had managed to get out of whatever pocket markets they were in as local artists and connect with a New York gallery were by the late 1980s already near 10 years into substantial contracts with their patrons, and influencing the annual June crop of art school graduates with multiple exhibitions nationally and in Europe.

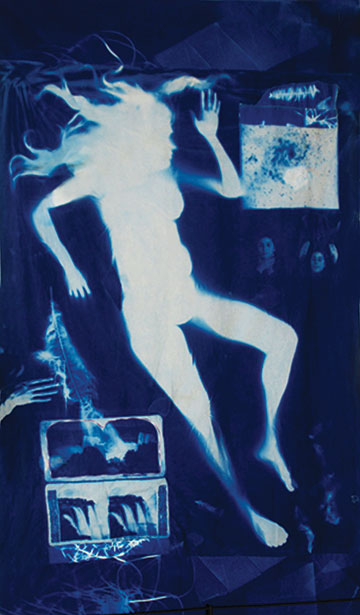

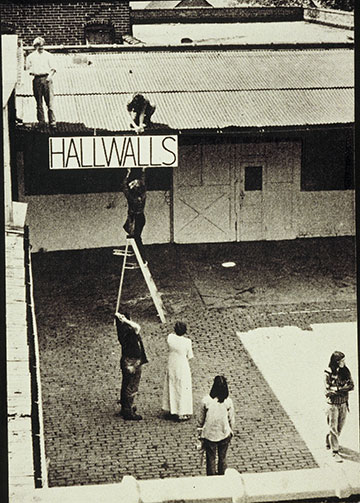

Three came from Buffalo, two painters and a performance/photographer. They were and remain significant artists who summarily defined the post-modern context of art expressed not in a reflexive, contemplative way but in the larger context of contempt for and alienation from a society whose technologies produced art that offered merely orderliness or merely chaos. Art had apparently finally come to reside in the bridled imagination of its spectators, whose minds, daily dosed with the generally desultory state of the world condition, require a certain palatable mixture of orderliness and chaos to stimulate their artistic appreciation. ultimately providing a positive rationale for existing more or less comfortably inchoate. In the early 1970s, Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, Charles Clough, and others founded Hallwalls, Buffalo’s long-standing premier nonprofit arts venue, using grants from the New York Foundation for the Arts. All three gradually came to create forceful, enigmatic artworks in human scale either in image or in the manipulation of materials.

Longo worked figuratively on canvas in high contrast black-and-white, characterizing figures in meditations of violence silhouetted in suits and ties, throwing punches, flailing wildly, launched into midair as if shot out of a cannon or falling from a great height. The opening graphics from Mad Men reference his work with the “falling man” image.

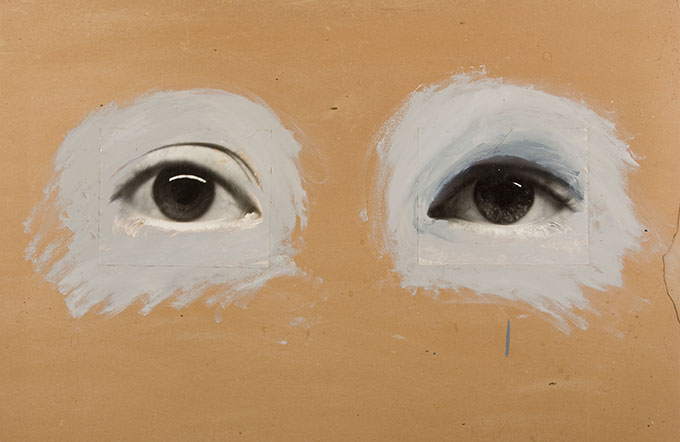

Cindy Sherman used her own face and figure in guises inspired initially by movie stills, creating stylized characterizations that alternately mocked and flattered female stereotypes. Her attention to make-up, her costumes, her lighting, and her body language made her signature images seem distinctly familiar; yet, on second look, they appeared to stare back at the viewer from an inscrutable distance. Her work is presently the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Charles Clough made paintings in bold, hand-worked accretions, each revealing something of the previous layer in vibrant palimpsests charged with polychromatic arabesques. All three found success in the New York art world fairly early on, and remain fixed stars high above the now sprawling panoply of neo-recidivist “ironistas.”

•

Characterizing movement toward chaos, “entropy” might be seen as a recurrent theme of the late 20th-century cultural matrix. The Albright-Knox Art Gallery’s exhibition, Wish You Were Here: The Buffalo Avant-garde in the 1970s, examines this inescapable tendency (declared to be the Second Law of Thermodynamics) with a retrospective of the myriad artists living and working here, as well as those invited to exhibit and/or teach here, in that inherently chaotic decade. Much of the work focuses on the passing of ideologies and the excursions of modernism in to the realms of pop art and performance. In the late 1960s, the rise of cultural and inter-disciplinary studies departments in universities and art schools produced a post-graduate disposition running counter to classical aesthetic underpinnings; artists, writers, and musicians, ignored by commercial venues, gathered in collaborative art spaces—unfinished lofts with plywood and sheet plastic lit by clamp lamps trailing extension cords—abandoning melody in music, plotting in fiction, human proportion in architecture, and representation and perspective drawing in the visual arts, but finding a new spirit of synergistic opportunity.

Along with major artists of the era, such as Joseph Beuys, Chris Burden, Hans Haake, and Dennis Oppenheim, the artists, musicians, and filmmakers of the Buffalo avant-garde explored the twilight edges of modern manners and madness.

•

In late summer 1975, we were living in Baltimore, while my then wife attended the Maryland Institute, taking classes in photography and painting. Graduated from the Cooper Union School of Art in New York the previous year, but with my hope of getting into graduate school at Yale fading, I had taken a job helping a sculptor friend renovate playgrounds in Baltimore’s inner city neighborhoods. (We didn’t call them that then; they were called “the ghetto.”) Picking me up early mornings in his long bus-like van full of welding gear and oxygen acetylene tanks, he would slide in a cassette tape during the drive to the work site. The music was unfamiliar to me, ensemble jazz but infused with electronic elements, synthesizers, and drum loops. It rose and fell in long, echoic solos on keyboard and percussion. I was taken with it immediately: Pat Metheny, a Missourian, like me, from Long Jack, not far from where I had grown up in Odessa.

The sculptor played other artists even deeper into electronic-assisted composition: Terry Riley, Stephen Reich, John Adams, and Philip Glass. I was going to need those experimental composers to get through the 1970s of bubble gum pop, heavy rock, and disco. The music of Eric Dolphy, Anthony Braxton, and Ornette Coleman all stepped up to help me working in studio while I struggled to express myself in paint and writing after a day hoisting a 27-pound metal grinder.

In Buffalo, a similar musical awakening was taking place alongside the visual arts in collaborative artistic communities across an entire spectrum of music, film, video, and performance art. Like Baltimore, Buffalo was a city that losing its century-long manufacturing ethos; Buffalo was the Queen City of the Rust Belt, its population practically comatose from the insidious impact on its economic livelihood, but with a burgeoning academic identity. Beginning in the late 1960s, during the height of the Vietnam conflict and the struggle for civil rights, disillusionment with the government and authority figures generally had produced a generation of disaffected but college-educated, talented youth—the “counterculture” of Time and Newsweek parlance. But they were not so disaffected that in their opposition to the “establishment” they dropped out altogether. Their antipathy to hierarchy created an impetus to collaborate across cultural institutions and organizations that came to define the arts in the 1970s, particularly in Buffalo.

Some began to see a future in promoting the city’s higher education, cultural, and research assets. As in the visual arts. creativity in music, film, and literature was greatly aided by the collaboration, which was in turn encouraged by a cash-poor intellectual environment. The practical necessity of sharing resources provided cross-current opportunities to obtain grants for innovative programs and venues.

In music, hybridization was fueled by momentum from publically funded initiatives, which brought known modern composers together with eclectic electronic wizards, computer hacks, videotape and film artists, all converging in experimental practices across media and genres. Critical to the dissemination of “New Music” was the partnering of the University at Buffalo with the Albright-Knox, which, under its director Robert T. Buck Jr., brought to the public untested performances by John Cage, Morton Feldman, and Max Neuhaus, as well as bringing greater visibility to the proliferation of Buffalo’s young, subversive, countercultural artists, who were largely unrepresented by established galleries and museums.

In Feldman’s work especially, the aesthetic of combining visual art with music was especially strong and reflects the unsystematic approach to art coming out of Buffalo during the late 1960sand early 1970s. Concurrent with the experimental developments in music were diverse artistic practices in film and literature, again fostering collaboration and cross-disciplinary resourcefulness as the climate for arts funding became increasingly competitive. Aggressive pursuit of available grants propelled alternative art spaces to broaden their initiatives, inviting writers and poets to perform, further de-systemizing previously distinct disciplines. Broader public interest in the dynamic cut and thrust of art events and exhibitions offered by the Albright-Knox, CEPA, the Center for Exploratory and Perceptual Arts (or CEPA), the sprawling acreage of outdoor art works at Artpark in Lewiston, and UB’s Media Studies Department was chronicled almost daily in the Buffalo Evening News, championed by then art critic, Anthony Bannon, who, like Clough, has recently returned to Buffalo.

•

In the spring of 1990, I was given a letter of introduction by a New York City painter friend to meet the controversial but no less celebrated film artist, Paul Sharits. By then the political landscape had changed. The public funding that had spurred the cultural arts juggernaut of the 1970s had gradually ground to all but a halt. Alternative art spaces had ceased operations or were drastically cutting back. The country was in the throes of the “culture wars,” as divided over funding for the arts as it has come to be over the whole ideological spectrum today, two decades later.

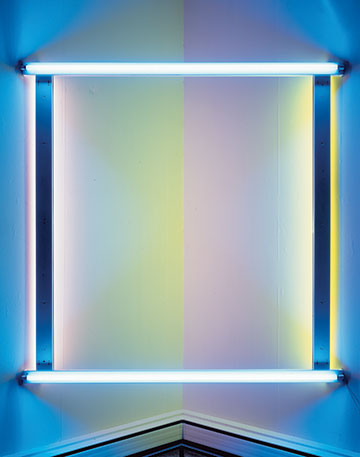

Sharits had become the single film artist to move beyond the “media arts” movement of the 1970s. His work was seen as bridging the gap between abstract painting and structural film and video artists more aesthetically interested in conceptual work, using dialogue, theater, and performance emblematically. Using looping 16-millimeter film, four projectors rigged with a complex of angled mirrors projected on a wall, Sharits created an installation interfacing looping frames of film in a continuous, linear alignment, producing overlapping frames of rich, shifting hues of reds and blues accompanied by a intently jarring soundtrack of shattering glass.

Both a brilliant polymath and a troubled, complicated individual, Sharits was a kind of living treasure in Buffalo’s arts community. His house was full of students living, visiting, and just hanging out in various semi-reclining arrangements. Welcoming me with an absentminded handshake, he spun from room to room in a whirl of critical observations and pronouncements punctuated by increasingly paranoid rants and outbursts, culminating in a walk to his favorite restaurant. As he opined on the state of art and politics amid his admiring lunch guests, a lone, tall figure approached the table and without a word picked up Sharit’s plate and spit in his salad.

In the Albright’s retrospective exhibition, there is a prevailing sense of theatrics, recounting the actions, events, and ephemera of the period—a deadpan, even mordant humor inherent in concerns basic to artistic expression, presenting the artists as storytellers, dreamers, guides, and shamans, all given free rein to prod, provoke, even tickle the audience. Their works have in common a sense of inexorable decay—of civility, morality, and social coherence—throwing this pejorative outcome at the viewer as deftly as a Frisbee. Delicately, brutally. Sometimes whining, cajoling, preening, quizzical, often beautifully, the show groks. It will close July 8. It is not to be missed by anyone who still knows how to throw a frisbee.

As a welcome addendum to the exhibition and a fine art document on its own, the catalog to Wish You Were Here: The Buffalo Avant-garde in the 1970s presents a fully comprehensive overview of the era in an excellent essay by curator Heather Pesanti, along with archived photographs and interviews with all the principals involved in Buffalo’s period of “radical creativity,” examined from an art-historical perspective 40 years out.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v11n26 (Week of Thursday, June 28) > That '70s Show... This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue