Bobby Jackson and a Blood-Soaked Old Glory

by Patrick Sawyers

Friday, October 22, 1976, was a chilly afternoon in downtown Buffalo, with traces of frozen rain and a wind blowing faster than usual. Suddenly, though, one strong gale from the west, coupled with one man’s shocking act of self-destruction, caused the already dreary day to turn chilling and macabre.

The event has since become a local urban legend: back in the ‘70s a man committed suicide by jumping from the top of Buffalo City Hall when a freak gust of wind came along, changing his trajectory and impaling him on the flagpole above the main entrance. To those on hand to witness the suicide it was a jarring spectacle few of them would ever forget.

By 3 p.m. more than 200 people had gathered in Niagara Square, where sirens were blaring, police lights flashing and authorities were frantically barking out orders. A crane had been called in to assist firefighters sawing off the flagpole at its base, and medics were extracting the lifeless body of a young man dangling limply at half-mast. The streets were closed off and traffic was at a standstill, with motorists gazing up in horrific disbelief and City Hall workers craning their necks out of their office windows for a better view.

The victim was identified as Robert Leroy Wayne Jackson, a 19-year-old black male with no known criminal or psychiatric record. Over the next two days the Buffalo Evening News and the Buffalo Courier-Express ran brief front-page articles, but little information was available and no real follow-up was done. In its December 9th issue Jet magazine carried a stunning photograph, a close-up of Jackson’s impaled body, but the accompanying article shed little light on the grim circumstances of his violent demise.

Whatever was driving him on that afternoon, Jackson found himself riding the elevator up to the highest floor of Buffalo’s 32-story City Hall. Completed in 1931, the Art Deco building stands 398 feet from bottom to top. On the 28th floor is its famed observation deck, a narrow walkway that wraps around the building’s exterior, allowing visitors a majestic 360-degree panoramic view of the city through an eight-foot-high protective glass wall.

According to its sign-in book Jackson reached the observation deck around 2 p.m. He approached security guard Edward Dzielski, politely asking for directions to the nearest restroom. “He left and was gone about eight minutes...then he came back.” Dzielski told reporter Marshall J. Brown of the Buffalo Courier-Express. “He was looking out the windows, and then I saw him wiping his eyeglasses on his jacket so I gave him a Kleenex. He looked at me and said, ‘Thank you,’ and he wiped his glasses clean with the tissue.”

For about 40 minutes Jackson wandered the deck, circling the outside of the tower and gazing out over the cold, blustery city. Shortly before 3pm he stood on the tower’s east side, positioned directly above the building’s main entrance and looking toward the McKinley Monument and beyond. What happened next will remain forever unclear, but it seems Jackson hoisted himself up and over the eight-foot glass enclosure. (This would not have been difficult to accomplish, as the width of the deck area is only about three feet, plenty of room for a man to shimmy himself to the top using the building’s brick wall for leverage.) For a moment he sat perched, summoning up his nerve and bracing himself for what would have been a 28-story fall were it not for the 4th-floor landing jutting out 250 feet directly below him.

Stretching upward from that landing stood a 40-foot flagpole, and as Jackson plummeted down the front of the building a sudden blast of wind from Lake Erie carried him a good fifteen feet to the east, placing him directly above the aluminum mast. By now he had flipped around and was facing up toward the sky, and as the flagpole pierced his back Jackson’s weight and momentum dragged its flag down along with him, both of them coming to rest halfway down its base. A blood-soaked Old Glory remained partially tucked inside of him, its other half waving casually in the breeze.

Only a handful of the horrified onlookers actually witnessed the unbelievable event. One of them was 14-year old Michael Caputo, who should have just been getting home from Iroquois Middle School. But Caputo, a self-confessed “juvenile delinquent,” had a habit of cutting school and taking the bus from his East Aurora home to downtown Buffalo, where he would roam the corridors of City Hall trolling for loose change in phone booths, elevators and newspaper boxes. He would then take the day’s winnings to now-defunct novelty shop George & Company, counting out his nickels and dimes and usually walking away with a novelty gag for under a dollar.

Caputo recalled that October afternoon. He happened to glance up at the top of City Hall, he said, and noticed a man teetering on the precipice. “I spotted him just as he jumped,” said Caputo. “It’s kind of freaky, but the way I remember it he was going straight down and all of a sudden he just was blown straight out [directly over the flagpole]. It was almost like somebody blew him out there.”

The crowd, at that point, was only fifteen or twenty strong, but within minutes sirens started howling and police began swarming the area. “I was freaked out because of all the cops,” Caputo explained, “because I was always worried about getting nabbed for truancy when I was downtown during the school year.”

As workers poured out of City Hall and spectators congregated in Niagara Square, Caputo heard the unmistakable sound of loose change hitting the pavement—coins, he knew, that could only have come from the dead man’s pockets 150 feet above. “I heard the noises and I looked down and there were all these quarters,” he said, “Everybody else is looking up and I’m watching these quarters fall from the sky. I could never say that I actually saw them coming from his pocket, but all of a sudden it was like the sky had just opened up and started raining change.”

Scooping up the coins Caputo made a beeline for George & Company, and it wasn’t until he’d arrived back home that he was able to fully comprehend the gravity of what he had just witnessed. “It really struck me as surreal at first,” he reflected. “I remember thinking of it as...kind of like a comic...a graphic novel that just unfolded in front of me...To me, looking back on my life, that was a pivotal moment where I think, like a pinball machine, I bounced off of that bumper and ended up going in a whole different direction.”

Paramedics removed Jackson’s skewered body from the flagpole, loaded him onto a waiting gurney and covered him with a sheet. Erie County Medical Examiner James J. Creighton pronounced Jackson dead on the spot.

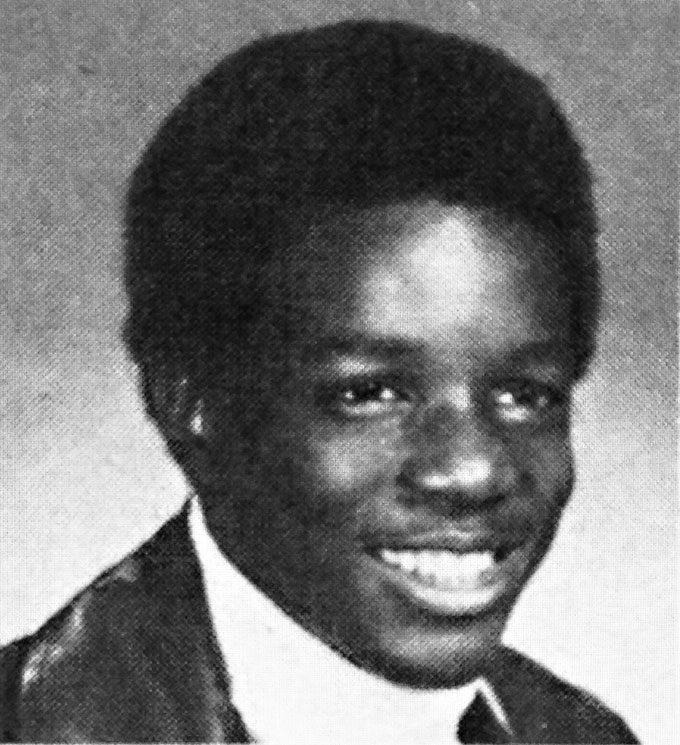

Bobby Jackson, according to his younger brother Lee Anthony Jackson, “was cool”—not at all unhappy and hardly a candidate for suicide. His photograph shows him to be a pleasant-looking young man with a smile that suggested a gentle kindness. To his family, nothing indicated he was despondent in any way, let alone wrestling with demons so profound they would drive him to suicide.

“I was with him just last night and he was in good spirits, no problems,” 16-year-old Lee insisted to Mike Vogel of the Buffalo Evening News on the afternoon of his brother’s death. “You can ask any of his friends, Bobby just wouldn’t have done this to himself.” In fact, Lee noted, “he’d already talked to my mother, told her just what he wanted for dinner. She’d gone ahead and fixed it, and she was waiting for him when the call came.”

His sister Judy told a reporter from Jet magazine that she had seen her brother just days earlier, and he was his usual buoyant and optimistic self. “Whatever problems he had he must have kept them inside,” she remarked.

Jacksons’ 38-year-old mother Jean May Lark had done well raising Bobby and his siblings in their modest home at 197 Grey Street, a two-story dwelling on the city’s East Side. Bobby, her eldest son, went through elementary School 82 and middle School 8. He attended Riverside High School, graduating in 1975. According to assistant principal James Farley, Bobby was “one of those students who went through four years of school, did his work and didn’t get into any trouble.”

After graduation he enrolled at the University of Buffalo as a psychology major and commuted daily to the Amherst campus. Bobby had recently moved out of his family’s Gray Street home to an apartment at 52 Locust Street, where he lived alone on the sleepy one-way street.

His mother recalled Bobby being talented at chess and “very interested in life, interested in the future.” Lee noted that his brother’s “main goals in life were the pursuit of love, knowledge and money.” A passage from Bobby’s diary, however, does hint at some measure of cynicism and disappointment. “Life is not fair and never has been,” he wrote. “It may have been fair once, but don’t count on it.”

Back at the Erie County Morgue the death of Robert Leroy Wayne Jackson was officially ruled a suicide. Jean Lark was then faced with the unenviable task of identifying the shattered body of her first-born son, and Lee Jackson the older brother he had long admired and looked up to. Neither seemed willing to accept that Bobby had chosen to end his own life. Both suspected foul play, but Police Chief Leo J. Donovan insisted there wasn’t much to support that contention. He acknowledged a few peculiarities, such as torn clothing and a scratch on the victim’s cheek not there the night before, although it’s tough to say how much follow-up was done or how thorough the investigation.

To this day, nearly four decades later, there still remains an air of mystery surrounding Bobby Jackson’s gruesome death. Beyond the family’s steadfast belief that this was no suicide, there is also the matter of little public record or information. In response to a 2014 Freedom of Information Act request, Buffalo Police Captain Mark Antoni issued a formal statement indicating, curiously: “The Buffalo Police Department has conducted an extensive search for these records and have been unable to locate them.”

During this same era, Mike Caputo got caught stealing coins from an unattended newsstand in the Ellicott Square Bldg. and a then unknown Carl Paladino furiously booted him out of the building, kicking him several times and warning him never to show his face again. 35 years later Paladino hired him to manage his 2010 gubernatorial campaign.

blog comments powered by Disqus

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n43 (Week of Thursday, October 23) > Bobby Jackson and a Blood-Soaked Old Glory This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue