The Great Beauty

by George Sax

Sense of sensibility

The Great Beauty

During the first few minutes of Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty, viewers may well wonder if they’re watching a remake of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita from a half-century ago. It opens with brilliantly lit shots of Rome’s ancient monuments and renaissance fountains, intercut with a scene of intense, large-scale nighttime partying on an expansive terrace. In the midst of these appositions, a Japanese tourist takes a photo and drops dead.

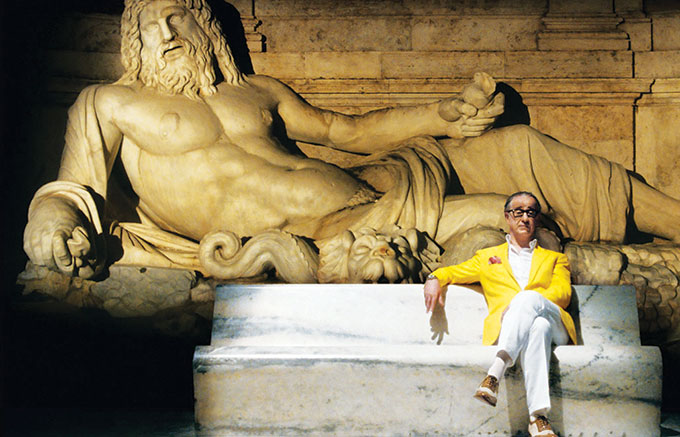

Back at the rooftop party, Sorrentino’s protagonist Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo) dances to a disco beat as a sombrero-wearing mariachi band winds through the throng. Jarring juxtapositions recur throughout The Great Beauty.

Jep’s Rome may at first resemble the Rome of Fellini’s Marcello, the passively corrupted journalist in the older film, and Jep may remind one of the younger earlier character. In fact, Sorrentino’s film—the Italian entry in the foreign film category of this year’s Oscar race—may strike some as a sequel to Fellini’s. But there are problems with this reaction, not least Sorrentino’s probable rejection of it, judging by his comments. For another thing, it’s a lot harder to get a fix on what he had in mind. Fellini’s point of view might not have been profound but it was clear enough: modern society, including the church, had been morally corroded and degraded. And he had a lot of fun showing us this. Sorrentino’s picture may reflect his enjoyment in making it, but it’s far less clear what he was trying to convey. Sometimes it seems as if he was just reveling in the striking effects he could create and string together.

Jep, we soon learn, wrote a well-regarded novel 40 years ago, and never wrote another. He’s become a successful cultural and celebrity journalist, and a sybaritic social figure. The party at the beginning was on his 65th birthday. Not long afterward, he’s visited by the husband of a woman Jep had wooed and lost many years ago, who tells him she has died. This news is apparently supposed to bring him up short and move him to meditate on his life, except the movie depicts little change in his habits and schedule. He continues to wander his beloved city, going to elaborately ostentatious parties, flirting with, and occasionally bedding, much younger women.

Jep is an amusingly soigné cynic about his vacuous social set and himself. (“The best people in Rome are the tourists.”) The people he knows are a superfluous, even parasitic stratum. The only “ordinary” person in the movie is his tart-tongued housekeeper. Sorrentino pokes mildly caricatured fun at these people, but he’s as tolerant of them as Jep is.

The Great Beauty glides along with Jep in his largely vacuous, almost aimless rounds, the camera panning, tracking, and sometimes closing in on a starkly lit face. Eventually, the film seems to be cycling around, in and out of short, abruptly cut scenes, with no real development. It becomes a sort of cinematic onanism.

Finally, The Great Beauty seems to be about self-referentiality. At one juncture, Jep says, “I was destined for sensibility.” Sorrentino’s film seems to be about his own sensibility.

Watch the trailer for The Great Beauty

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v13n5 (Week of Thursday, January 30) > Film Reviews > The Great Beauty This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue