Controversy looms over ASi, the winner of the 43North competition

by Ethan Powers

What's the Big Idea?

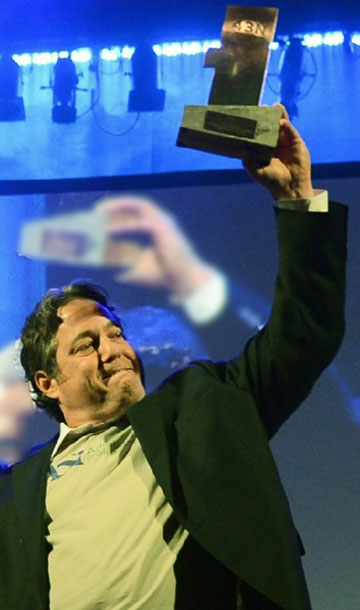

On October 30, 2014, a packed crowd at Shea’s Performing Arts Center watched Glenn Thomas accept the $1 million grand prize from the “world’s largest business idea competition” organized by 43North. The excitement was palpable as a local company from Tonawanda with a revolutionary metal forming idea beat out almost 7,000 entries from 96 countries and all 50 states. The Buffalo News, Business First, Artvoice and local broadcast media all covered Thomas’ Tonawanda-based Adiabatic Solutions, LLC (ASi) in its momentous victory. It was unanimously chosen as the winner.

Not everyone was so ecstatic, however. In fact, Lennart and Susan Lindell of Lindell Research & Engineering in DeKalb, Illinois are livid. The married couple claim the adiabatic process which could revolutionize modern manufacturing was not in any way, shape, or form developed by ASi or CEO Glenn Thomas as has repeatedly been implied to the media. And the Lindells, who were once in business with Thomas, have the paperwork and documents to prove it.

“We broke bread with him. We had him sleep at our house. We really thought he had our best interests at heart. This really hurts,” said Susan of Glenn Thomas.

The adiabatic process uses a high velocity impact to set a metal into a softened, gel-like state for a fraction of a second, allowing it to be pressed into a mold. Lennart Lindell’s ties to the adiabatic process reach back to 1960s in Sweden. By the early 1980s, Lindell arrived in Illinois with the blueprints of adiabatic cutting equipment based on work he had done at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. United States Patent Office records show Lindell’s first patent for the adiabatic process was granted to him in January 1981 for the impact press. He was granted a second patent in relation to adiabatics in 1984, this time for the invention of the tooling assembly, which allowed the machine to cut blanks from elongated stock of material such as rods, bars and tubes.

With the adiabatic technology patented, Lindell created LMC, Inc., and focused on building a reliable adiabatic cutoff machine that would save time, energy and material. LMC soon started to produce high-velocity, adiabatic cutoff machines for manufacturers.

Lindell attributes his early successes to the fact that he was the only engineer crazy enough to continue investing time and research into a process that was considered to merely be theoretical, according to the engineering community.

“A lot of big companies, big institutions around the world were researching the same thing as I was, and basically they all gave up,” said Lindell. “I was a young, cocky engineer at the time. I was going to show them by going back and working harder on it.”

The work began to pay off. In 2001 Lindell and LMC were awarded one of Research & Development Magazine’s R&D 100 awards—a yearly list compiled by the publication recognizing the most significant technology innovations of that year.

A former employee of ASi parent-company Pacer Bioscience, who at his request we’ll refer to as “James” adamantly sought to speak to us for the purposes of this article, noting that he yearns for Lindell and LMC to get credit for their invention. James was let go from Pacer in 2011 due to financial instability related to the company. “I have a lot to gain if Glenn is successful,” he said. “But my concern and some of the reasons I’m not working there [Pacer] anymore is, for lack of a better term, Glenn’s conscience as far as telling the whole truth.”

James was present in 2004 when Thomas, then an employee of Greatbatch Inc., was first introduced to Lindell’s adiabatic technology. Thomas was so enthusiastic about the adiabatic process that he requested Lindell fly to Clarence, NY for a personal meeting with Wilson Greatbatch. Lindell did so, presenting his technology and process to Greatbatch, with Thomas present, as well.

A trove of emails and communications between Thomas’ ASi and Lindell’s LMC, obtained by Artvoice, show the extent to which Thomas initially tried to obtain an exclusive use for Lennart Lindell’s adiabatic forming machine. By 2006, Thomas, no longer employed by Greatbatch Inc., founded Pacer Bioscience Inc. It was his vision to establish a partnership with Lindell’s LMC in which Pacer would raise capital, LMC would build the adiabatic forming press, and the two companies would provide medical components including orthopedic gears and surgical tools using the adiabatic process. This business partnership was to be developed under a new company called AdiaMed, incorporated in October 2006.

James states that the reason that AdiaMed never achieved the success envisioned, and was eventually dissolved, was the result of Thomas’ increasing interest in algal pyrolysis—the potential use of algae as a feedstock for next-generation biofuels. Yet algae-based fuel production has been studied for years and remains outside the realm of economic feasibility, and research has proved costly and not fruitful enough to remain a viable concept. Nevertheless, Thomas decided to invest Pacer’s time, money, and resources into pyrolysis and away from adiabatics. When, according to James, this endeavor proved to be financially unsuccessful, Thomas re-focused attention back to adiabatics.

However, the transition back into business with Lindell immediately became tumultuous when Thomas listed himself as a primary inventor on a patent application in relation to a method for compacting a powder material using a high velocity adiabatic impact. Patent number “61104173” titled, “High Velocity Adiabatic Impact Powder Compaction” was filed by Thomas and required Lindell’s signature, which he vigorously refused to give on the grounds that Thomas had falsely attributed himself as an inventor.

“I told him, ‘I’m not going to sign this. This isn’t right.’ ... He had no part in the patent, in the work and research I’d done,” said Lindell.

Lindell stated to Thomas in a letter, “I do not find any evidence in this patent application that allows you to claim yourself as an inventor. It is agreed that you were here periodically visiting LMC and viewing powder compaction samples, but you offered no new input to the work that I was doing.”

Thomas contends that he contributed nine of the 20 claims essential to the patent. When pressed by Artvoice to list what exactly those nine contributions were, Thomas declined and instead said via email that “ASi is focused now on moving ahead with our business plan. We are not going to get into further arguments with Lindell through your newspaper.”

Tensions between LMC and ASi became even higher when LMC began to run into significant financial strife in 2008. Further adding to the company’s predicament was that Resource Bank of DeKalb, Illinois—the bank LMC had gone through in order to obtain business loans—came under federal investigation for surreptitious credit practices. The Comptroller of the Currency of the United States put forth an agreement to the bank’s Board of Directors in which the Comptroller plainly states that it has “found unsafe and unsound banking practices related to credit administration at the Bank.” Resource Bank, facing financial instability itself, called the Lindells’ loans. LMC was forced in October 2008 to let go of its entire staff. In November 2009, the bank took control of all the assets and foreclosed on the LMC building. At this point, the Lindells worked with prospective clients from home. Vendors would provide the space for Lennart to build and run his machines.

Amidst Lindell and LMC’s financial difficulties, Thomas and ASi began to try and assimilate Lindell into their own company along with Lindell’s research and patents. A commercialization contract written up by ASi and put forth to Lindell in 2008 states that it was the intent of ASi to purchase a forming press designed by Lindell and would give ASi the right to manufacture his machines. In return, LMC would receive 2 percent of all revenues generated by machines assembled by ASi, and would get a 25 percent ownership in ASi plus 3 percent of all ASi technology sales.

However, friction between the two parties came to a head in March 2009 following a series of tests, organized by Pacer Bioscience, run on the adiabatically formed shells produced by LMC. In a letter dated March 18, 2009, sent from Pacer’s VP of Business Development Joe Probst to Lindell, Probst summarizes that the three tested samples exhibited cracking on the radius shell.

Lindell claims that the test that resulted in crack formation was a test requested by Thomas to form the cases with only the power stroke and not with the full adiabatic impact.

LMC President Gordan Goranson, in an email to another LMC board member, expressed his desire to cut ties with Pacer altogether following Probst’s letter. “According to Lennart there are reasons for the cracking and mainly with the way in which we are completing the samples for them without having the proper press, and adequate cash to carry on this research,” he wrote. “Pacer raised over 600,000 for themselves because of the work that we are doing for AdiaMed and we get basically nothing.”

How the adiabatic machine currently in the possession of ASi got to be there remains a contested topic. Thomas told Artvoice that Nibco, a manufacturer of valves, fittings and flow control products, gave LMC a purchase order in 2002 and that Lindell was supposed to deliver the machine in 2003. By 2007 he says, he still hadn’t delivered a machine that had met their specifications. As a result, Nibco took the machine from LMC, had Lindell sign a release, and decided to work on the machine themselves.

Lindell on the other hand, contends that the machine was shipped in April 2004, when LMC met their first financial scare. Nibco became concerned that the bank might confiscate the machine in the event of a foreclosure, and demanded that Lindell ship the machine immediately.

James’ recollection of events confirms that of Lindell’s, saying that Nibco took the machine because they were afraid the bank would seize it, not because it didn’t meet specifications. On the claim that Nibco took the machine and worked on it as a result of waiting too long, he noted, “If that were the case, why didn’t Nibco just make the machine themselves, rather than seeking out Lennart?”

What is certain is that the machine remained at Nibco until 2012, at which point Nibco sold the machine to ASi. As recently as 2010, Thomas and ASi were still actively pursuing Lindell and his technology. A business relationship chart sent from Thomas to Lindell in March 2010 offers him two options. One agreement would give Lindell an equity share with ASi in return for giving ASi the intellectual property rights for his forming and powder compaction technology. The other option offered Lindell a straight royalty with the condition that if Lindell were to contribute anything new to the patent, he would have to assign it to ASi.

The Lindells have consistently refused such offers over the years on the grounds that they do not give enough credit to Lennart as the sole inventor of the adiabatic technology. They say they were floored in November 2014 to learn that ASi had won the 43 North competition using their technology—technology they readily admit is within every right of Thomas and ASi to use considering each of Lindell’s patents are now expired.

According to documents from the United States Patent and Trademark Office, Lindell’s patent approved January 20, 1981 expired in 1998. Lindell’s other patent for tooling approved in 1984 expired in 2001. He was then granted a third patent in 2003 for an “Automatic two-station adiabatic blank cut-off and part forming system” (patent #6571596). The USPTO confirmed that this patent expired in 2007 due to non-payment of the 4-year maintenance fee, which the Lindells say had to do with their financial troubles and disputes with Resource Bank.

With the expiration of all three patents, Lindell’s adiabatic technology is now considered within the public domain. In other words, Lindell cannot exclude others from using it, but no one else can patent it, which has left the door open for Thomas and ASi to enter the market. The Lindells state that they are not claiming that ASi cannot use the technology, only that Thomas has received advantages for being disingenuous as to where it originated.

“There’s a big difference between what you can legally get away with and what you can morally get away with. And this is maybe one of those situations,” James said.

On December 3, 2014 the Buffalo News reported that the panel that allocates money from NYPA’s Niagara Power Project recommended the 43North business plan competition receive $6 million in funding so it can conduct a second competition next year.

But was the competition’s inaugural year tainted by a winner that misled judges as to where its distinctive technology came from?

Former Executive Director of 43North Andrew Pulkrabek spoke with Artvoice on his last day with the organization. Pulkrabek stated that when Susan Lindell had contacted him to notify him that LMC, not ASi, was the inventor of the technology, he tried to explain that very rarely can one person claim sole ownership and responsibility for an invention.

“When it comes to invention, no invention is the cause of just one individual,” he said. “I think she has a belief that her husband is the sole inventor for what ASi is purporting to practice by way of their business. The reality is that Glenn and ASi have many different portions of intellectual property, some of which may have come from Lennart Lindell. I cannot speak to that.”

Asked whether he believed the competition’s winner would have been different had Thomas and ASi noted in their presentation that a company in DeKalb, Illinois has manufactured and sold hundreds of these adiabatic machines, Pulkrabek stated that it would not have raised any doubts about ASi’s capabilities.

“I think the premise of your question is not correct,” he said. “That would not have changed anything, because everybody that is in business knows that invention comes from many different sources.”

Perhaps not everyone in business.

Artvoice reached out to all six of the judges who were in attendance at Sheas’s Performing Arts Center to hear and analyze the last pitches of the competition’s finalists on October 30, 2014. Four declined to comment while one was unavailable. The one judge who did respond spoke to us on the condition of anonymity.

“Obviously, no, we did not know this,” they said. “Honestly, this was never raised nor did anyone ask (about any of the companies) ‘Is this really their technology?’ We were told the due diligence had been thorough, and we believed that.”

When asked if the new information warrants a reconsideration of their vote for the winner, the judge said it would depend on how the information was posed to them. “If he [Thomas] had disclosed it, that would have been one situation. Since he did not, and assuming the other guy’s claim is true, of course we would not have voted for him. It’s not the facts but the cover-up that is so damaging.”

Susan points to the fact that Lennart held the very first patent rights on adiabatic forming, as well as his R&D 100 award as a refutation to Pulkrabek’s assertion that “no invention is the cause of just one individual.”

She also takes heavy issue with the Buffalo News and Business First, which have done stories on Thomas and ASi. Susan states that even after notifying these newspapers of the truth as to the origins of the technology, they continued to report erroneous, fabricated information. The Buffalo News has also consistently deleted her comments, she says, when she tries to point out the errors.

In an email to Susan in response to her concerns, one reporter wrote, “Everybody acknowledges you’ve sold the patent to Asi’s machine.”

“I don’t know where they got that from,” said Susan. “We never did any such thing.”

In November, Lennart and Susan received a cease and desist letter from ASi’s attorney to immediately stop “further attempts to interfere with the business affairs of ASi,” naming tortuous interference with contract and defamation as a potential charge if the Lindells continued to contact 43North. Susan believes it is the Lindells who should be sending such letters.

“Our trying to set the record straight about who invented the technology, should not interfere at all with their being able to operate their business, unless their business is predicated on the impression that they invented the technology,” she said.

When we reached out to Thomas for comment on the concerns of the Lindells, he maintained that ASi are the world’s foremost authority on the adiabatic function, not Lennart Lindell.

“Our business plan is entirely different than what they want to do,” he continued. “They want to build machines and sell them, which is a money-losing proposition … We’re selling products made off of these machines.”

Susan notes however, that Lindell Research & Engineering Center LLC, founded in 2010, have learned the lessons from the now defunct LMC. She admits that having an entire business’s capital invested in expensive machinery was not a profitable model. She says that the new company works in conjunction with investors who wish to manufacture parts by offering a joint venture with a royalty agreement.

“He’s not the expert on rapid metal forming. Nibco are the experts on rapid metal forming, and now we are the experts on rapid metal forming,” he said.

Thomas is adamant that Nibco in conjunction with ASi have improved the machine. “Over 80 percent of the functionality related to this machine was put in by Nibco,” he said. Thomas also contends that Lennart’s work on the machine was minimal. “The only thing that Lennart did on the machine was energy delivery,” he said. “His patent on that is long expired.”

Susan rejects any notion that ASi has done anything to enhance the adiabatic function, which is the heart of the machine, noting that when LMC sold Nibco that machine in 2003, it was already producing those copper plumbing “T” parts that the media has frequently shown in photos in conjunction with ASi.

“We know that they added a new controller, preheat unit, and a feeder,” Susan wrote via email. “Nothing that they added had any effect on the adiabatic forming part of the system which is the revolutionary and unique thing about the system.”

The adiabatic energy delivery that Thomas refers to, according to James, is the heart of the machine, without which, no other part matters.

“Let’s say you invent a vacuum. Someone else comes along and puts a new hose on it and a fancy bag. Do they get to say they developed 80 percent of it? The only function of it that matters is still the one that sucks up the dirt.”

James observes that the tragic element of the story is of a man whose life’s work has been the development of this technology, which has been consistently targeted by people looking to take credit for it or use it as a platform for their own successes. Now, he says, Lennart and Susan Lindell simply want people to know that it was Lennart Lindell who invented the adiabatic process, and that no one company has cornered the market on it.

“There aren’t many people that spend their whole life doing something,” he said. “That’s all he’s ever done, and part of that has been defending from people stealing or not giving him credit for what he did. It is now and has always been in my heart to see Lennart and Glenn work together as I believe it is the best solution for success for both parties.”

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v14n1 (Week of Thursday, January 8) > Controversy looms over ASi, the winner of the 43North competition This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue