Next story: Free Will Astrology

Brave Hart

by Peter Koch

Sergeant Patrick Hart spoke calmly into the receiver. “Honey, I’m not coming home,” he told his wife, Jill. “It’s okay, I’m with friends. I’ll contact you in a few days.” And then he hung up the phone.

Jill Hart sat dumbfounded in the couple’s Fort Campbell, Kentucky home, knowing she was supposed to pick up Pat from the Clarksburg Greyhound station later that day. He’s such a practical joker, she thought after a while, he’s probably coming home early to surprise me with Ozzfest tickets or something like that.

But Pat Hart wasn’t joking, and he didn’t come home, not that night or the next. As it turned out, he was 800 miles away, in another country, where in two days he would officially be AWOL from the United States Army.

Four days earlier, on a Thursday, Pat had boarded a bus for Buffalo, his hometown, where his parents still live. He was on a four-day pass, his “last little fling” up in Buffalo before deploying to Iraq. He planned to see a Bills preseason game with his parents, Jim and Paula—“To see if J.P. Losman is the real deal or not,” he told his company commander—and to visit the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. But Pat had other plans in Toronto, too. Unbeknownst to anyone save his parents, the nine-and-a-half-year veteran was considering deserting the Army and claiming refugee status in Canada.

Pat doesn’t look like one might expect, or at least he didn’t look like I expected him to. When I visited the Harts in Toronto on a misty gray Thursday last month, I was expecting a thin, tightly wound, clean-shaven guy with a high, short crew cut. Though he still has the bulldog build of a career soldier and an Army crew cut that’s growing in, Pat has allowed his goatee to grow long and bushy, and he wears a Nike t-shirt that exposes his heavily tattooed arms—everything from an anarchy symbol to Jill’s name. As he told me the story of how he and Jill and their three-year-old son, Rian, ended up in Toronto, he smokes cigarettes like a chimney, sometimes setting the ashtray right on his lap. He and Jill are good storytellers—honest, clear and plainspoken—often finishing each other’s sentences, quirky details and irregularities cropping up here and there. What they say is both significant and relevant in our war-weary times.

“My heart just wasn’t in it no more”

It’s impossible to pinpoint the exact moment when Pat—previously a mild-mannered, loyal soldier—decided he would risk everything to start a new life in a new country. One critical moment that Pat does recall, however, was during some down time spent a world away, in the middle of a forsaken Kuwaiti desert. He was stationed there in 2003 with the Army’s 541st Maintenance Battalion, ordering supplies for vehicles—Humvee tires, track shoes for tanks and the like. “I was like the Pep Boys of the Army,” he says. He also guarded the gates at several camps—Wolf, Arifjan and the Kuwaiti Naval Base—from behind a .50-caliber machine gun. It was there in Kuwait that some of his friends, returning from a deployment across the berm in Iraq, told him horrific tales, shared with him grisly photographs and made disturbing remarks about what they’d seen and done there.

“One of my buddies is telling me that he has a six-year-old daughter,” Pat says, “but now he sees the faces of these Iraqi kids that he’s run over every night before he goes to bed.”

Because of the increasing number of ambushes on convoys, an order was passed down early in the war that convoys were not to stop for anything. And Iraqi children, accustomed to convoys stopping and handing out food and candy, started getting run over. Pat continues, “His buddy standing next to him says, ‘I don’t know how many Iraqi kids I’ve pulled out of the front grill of my truck. Ain’t nothing but speed bumps to me.’”

The grisly photographs Pat’s friends snapped in Iraq began to haunt him. One series shows what happened when a truck failed to stop for a checkpoint that his friends were working: The truck is absolutely riddled with bullet holes, including about two dozen in the windshield. “They killed everyone inside, except for one,” Pat says. The sole survivor is being treated for bullet wounds in some of the pictures. Apparently, he says, the medics were angry that the guards didn’t kill him, too, for security reasons.

Another series shows two children who appear to have been burned by explosions or chemicals. Pat tellingly describes the first boy as being “about my son’s size.” Neither child can be more than three years old, and it’s impossible to look at their pained expressions and call them “collateral damage.” A third series, by far the most disturbing, shows corpses of mostly Iraqi soldiers, though some of the dead are conspicuously noncombatants. They have either burned to death or been killed by large-caliber machine guns. One dead Iraqi soldier’s index finger has been shoved up his nose by American soldiers, and the caption reads, “This is what happens when you’re picking your nose instead of watching your sector.”

“It’s just the disregard for a human being, you know…it’s a dead body.” Pat takes a long pause before continuing. “So I’m thinking, ‘If I go over there, am I going to come back mentally screwed up like those two guys? Am I going to be able to interact with my son properly?’ I love my son, I don’t want to do anything to hurt him.”

Then, in May of last year, Pat watched British Member of Parliament George Galloway fillet the US Senate, who’d fingered him in the United Nations Oil-for-Food scandal. In Galloway’s prepared statement, he turned the tables on the Senate, famously saying, “I told the world that Iraq, contrary to your claims, did not have weapons of mass destruction. I told the world, contrary to your claims, that Iraq had no connections to al-Qaeda. I told the world, contrary to your claims, that Iraq had no connection to the atrocity on 9/11/2001. I told the world, contrary to your claims, that the Iraqi people would resist a British and American invasion of their country, and that the fall of Baghdad would not be the beginning of the end, but merely the end of the beginning. Senator, in everything I said about Iraq, I turned out to be right and you turned out to be wrong, and 100,000 people paid with their lives; 1,600 of them American soldiers sent to their deaths on a pack of lies; 15,000 of them wounded, many of them forever disabled on a pack of lies.”

At that same time, Pat says, younger soldiers, 18- and 19-year-old kids, were asking him questions about the war because he’d been to the Middle East before.

“‘What’s it like, Sergeant Hart?’ ‘Why are we going over there? There’s no weapons of mass destruction, and Saddam Hussein’s out of power two years now.’ ‘Osama bin Laden’s in Afghanistan, he ain’t in Iraq, Sergeant Hart. What the hell?’” He found that he didn’t have any good answers for his men. “What could I tell them?” Pat says. “‘Shut up and do your job, because I’m an NCO and you’re a private, and you’re going to listen to me?’ That doesn’t hold much water when people’s lives are at stake.”

After hearing Galloway speak, Pat says, it was clear that his heart just wasn’t in it anymore, and that’s when he started thinking about desertion.

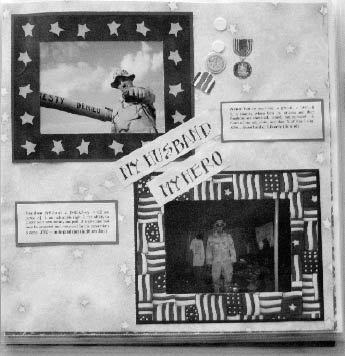

Watching Pat and Jill interact, it’s easy to imagine that this is how it has been all along: Pat making his decision to leave the Army and Jill standing steadfastly beside him. Both speak adamantly and easily against the war and against the Bush administration’s motives for waging it. But there are clues scattered around their simple apartment that things were once different. On the couch, two pillows brightly display the red, white and blue of the American flag. A homemade scrapbook sits on the coffee table, meticulously put together while Pat was in Kuwait. The pictures show a trim, tanned Pat Hart wearing fatigues and goofing with fellow soldiers, posing behind machine guns and on top of tanks.

But it’s what lies between the photographs that reveals the most. Each photograph is dressed up patriotically, with a border of stars or American flags. One page says, “My Husband, My Hero,” along with the definition of “America” and “freedom.” Another lists the seven values of the Army: duty, loyalty, respect, selfless service, integrity, honor, personal courage. This scrapbook was not assembled by someone who was ambivalent about the military.

In fact, if you asked Jill how she felt about Pat’s decision to leave the Army—a decision made, incidentally, on her birthday last year—she’d tell you that she “couldn’t even grasp how to support what he was doing.”

“Let’s hang our flag the highest, let’s wave it the proudest”

Jill Hart is a straightforward, cut-through-the-bullshit kind of person, reliable and strong. Over the years, she’s worked hard to help Pat advance his military career, partly for his own good, of course, but mostly for the good of their young son, Rian. When Pat decided to desert without consulting her, he turned Jill’s life completely upside-down.

“I remember thinking, ‘I don’t know what he’s doing, but this is my life and I’ve dedicated the last eight years to the Army and being an Army wife and helping Army families,’” Jill says. “‘I can’t walk away from this. I do a good job, I sleep really well at night. I’m a red, white and blue, flag-waving Army spouse. I don’t care what he’s doing, I can’t support this.’”

She is being quite literal about the red, white and blue; she decorated their house in Kentucky in those colors. The wallpaper borders were red, white and blue; the sofas were blue; and a huge picture of Rosie the Riveter hung on the wall next to the famous Time magazine cover of a sailor kissing a girl in Times Square on V-E Day.

“Our lives were, ‘Let’s hang our flag the highest, let’s wave it the proudest,’” she says.

If it’s true that there’s a woman behind every successful man, Pat couldn’t have had a better woman standing behind him. Besides being the head of the company’s family readiness group, which helps spouses prepare when their husbands or wives are deploying overseas, she also worked in the company commander’s office. She made sure everything was square for Captain James Pierce, made sure he always looked good.

“He referred to me, way up the chain of command, as his ‘efficiency expert,’” she says. “This was all a political maneuver. It wasn’t because I enjoy helping people, though I do, but it was all about how I could get myself between the command and my husband to ensure that he’d have the best career possible.”

She collected recommendations from officers for Pat to go to Warrant Officer Candidate School and made sure he was a “golden boy,” Jill says. “Anybody will tell you, they couldn’t touch Pat, because I did so much and he was so squared away.” Then he decided to desert.

On the day he went AWOL, Wednesday, August 24, Pat put in an afternoon call to Jill. “I think for the first 45 minutes of the phone call, I was ranting like a lunatic,” Jill says. “I wouldn’t even let him answer. I’d ask questions and just keep on talking.”

Finally, though, she ran out of steam, and Pat got a word in edgewise: “This is how I feel, this is how I believe,” he told her. “I’m not asking you to believe in it. I’m asking you to believe in me.”

That was too easy, though, Jill says. “I hadn’t made any decisions yet.” She was worried that he was endangering Rian by defecting. Rian has epilepsy, and his medication—four pills a day—is expensive. Jill was worried, rightfully so, that Rian would lose health coverage when Patrick deserted, and the medicine would be unaffordable. In fact, that health care was the main reason that Pat kept re-enlisting in the Army, against what he calls his “better judgment.” He spent his first stint in the military, from 1992 to 1995, in Germany as part of the 21st Theater Support Command. From Germany, he participated in Operation Provide Hope/Provide Promise, where he dropped food and medical supplies to war-torn Yugoslavia. After knocking around Buffalo for the next five years and finding nothing promising, he joined up again, and was assigned to the 541st Maintenance Battalion, which was deployed to Kuwait from 2003 to 2004. In Kuwait, he re-enlisted for three years, this time because he now had an epileptic infant at home, and no other prospects for a job with steady health care.

Surprisingly, it was the Army itself that, in the end, prompted Jill to cast her lot with Pat’s. On Thursday, the day after Pat went AWOL, she was on the phone with Captain Pierce. She’d been keeping him informed about Pat’s whereabouts, forwarding him Pat’s e-mails and letting Pierce know when he called. Pierce asked Jill if there was any way she could get Patrick back.

“I’ve been racking my brain,” she told him, “and there’s no way to get him back here. He’s set in his ways, this is what he wants to do, there’s nothing I can do about it.”

What the commander said next shocked Jill, and again turned her world upside-down: “Next time you talk to him, tell him that you talked to me and we’re going to shut down your Tri-Care [the Army health benefit].”

Jill asked, “Why would that get him back here?”

“I hope Rian doesn’t have a seizure,” Pierce replied.

In the next split second, while Jill’s rage rose from her stomach, Pierce went on: “Also, I could arrange something with Blanchfield [Fort Campbell’s Army hospital] where they could contact your husband and tell him you’ve been sexually assaulted, and he needs to come back right away.”

Jill’s mind was made up instantly. “Sir,” she said, the first time she had addressed him so formally, “this conversation is over,” and hung up the phone.

“You can do whatever you want to me,” Jill says now, “but you will not attack my husband or my son, because then the lion comes out, and that’s it.”

And that was it. Within 24 hours, Jill had a check in hand to cover the cost of a moving truck and gas, and five soldiers at the house, packing up their belongings—relocation benefits which were owed to Jill, according to the Uniform Code of Military Justice.

“The person who went wasn’t going to be the person who came back.”

Though he couldn’t tell Jill he was planning to desert—she acknowledges that she would’ve turned him in if she had known ahead of time—Patrick did have his parents’ support from the beginning. It was actually his father, Jim, who made initial contact with the national Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors (CCCO) and the War Resisters Support Campaign in Toronto on Pat’s behalf.

“Leading up to Pat’s deployment, I had a real strong sense that the person who went [to Iraq], whether he survived or not, wasn’t going to be the person who came back,” Jim says. So when Pat, home on leave last June, told Jim he didn’t want to go back, his dad started making the necessary contacts.

Jim and Paula Hart are gentle, soft-spoken people. Sitting in their Riverside home, only five blocks from the Niagara River, it is clear where Pat gets his gentle-hearted parenting skills. They say that he was a friendly and happy-go-lucky kid growing up, loyal to his friends. Not much has changed.

Leading up to his four-day pass in August, Pat had his parents nervous and slightly confused. “Sometimes I would talk to him when he called on his cell phone, and he would be the Patrick who had reservations about going [to Iraq],” Jim says. “Other times he would be talking about what he was going to do with his hazardous duty pay, or talking about Warrant Officer School.”

“When he came up,” Paula says, “we really didn’t know if he had made a decision yet about what he was going to do.”

So they settled on the premise that Pat was simply coming up for a visit.

Pat was sick to his stomach for the whole 25-hour bus ride up from Tennessee. “I hadn’t made up my mind yet. After nine and a half years, to desert the Army, it was just tearing me up.”

The Bills game on Saturday was an amazing 27-7 preseason rout of the Green Bay Packers, but “there was this cloud hanging over us,” Paula says. The next day they visited the Canadian National Exhibition. As Pat waited to make contact with the War Resisters Support Campaign, he missed his bus, so Jim bought him a one-way plane ticket to Memphis, just in case he had a last-minute change of heart.

The next day, Monday, they met Michelle Robidoux from the War Resisters Support Campaign, and Pat decided he had all the help he needed to desert. It was then that he took a deep breath, picked up the phone and called Jill.

Life, or 30 years

Today the family lives in Toronto, and it’s an uneasy existence at best. The high-rise where they make their temporary residence is much like any you’d see along Toronto’s waterfront, pleasant and non-descript. Inside, the Harts’ flat tells the same story—it’s nice, with a view of Lake Ontario, but the place looks bare. Several months after they moved in, the white-painted walls are still mostly bare, and half-packed moving boxes lie stacked in the corners. The television sits on the floor, and a strong wind off the lake—a wind that has transformed the lake into a sandy-brown, churning mess—blows through an open window, adding to the emptiness. The Harts have been slow to unpack because they still don’t have any confirmation that they’ll be able to stay in Canada. They’ve applied for refugee status through the Immigration and Refugee Board, but have yet to receive a hearing date.

There are other American deserters—although “war resisters” is the preferred term—currently living in Toronto. Two of them, Jeremy Hinzman and Brandon Hughey, have already applied for refugee status but were denied at their hearing last March. The ruling made very clear who qualifies for refugee status, and it seems that doesn’t include war resisters. Here’s what the ruling said: “I find that the claimants are not [Geneva] Convention refugees, as they have not established that they have a well-founded fear of persecution for a [Geneva] Convention ground in the US. I also find that they are not persons in need of protection, in that their removal to the US would not subject them personally to a risk to their lives or to a risk of cruel and unusual treatment or punishment, and in that there are no substantial grounds to believe that their removal to the US will subject them personally to a danger of torture.”

Hinzman and Hughey have appealed their case in Canada’s federal court, however, and nobody expects an official ruling on the appeal for months. There’s a strong possibility—or at least a strong hope among the community of war resisters and antiwar activists—that a parliamentary provision will be made in the near future, either changing the criteria for who can claim refugee status or simply allowing American military defectors to file for Canadian citizenship.

If no such provision is made, and Hinzman and Hughey lose their appeal, the Harts aren’t sure what they’ll do. If they go back to the US, Pat faces 30 years in federal prison. There’s always the possibility of trying another country, but none of the Harts have passports. “I really haven’t given it much thought,” Pat says. “I’ve got a positive feeling about his appeal in federal court.”

Times are a-changin’

Many readers will remember that during the war in Vietnam, it was relatively easy for American soldiers to cross the border into Canada and stay there. Canadian law has changed, however, inadvertently making it harder for deserters in particular. For historical perspective, I spoke with Lee Zaslofsky, coordinator of the War Resisters Support Campaign and himself a Vietnam-era war resister.

“During Vietnam, you didn’t have to apply for refugee status,” Zaslovsky says. “In order to stay in Canada as a permanent resident, you could make an application at the border.”

In other words, you could travel to the border as though you were just going for a visit, but then ask to apply for landed immigrant status. Applicants were interviewed and assessed, based on a points system that measured background, education, etc. “They could grant it at the border, on the spot,” Zaslofksy says. In fact, during that time, Pierre Trudeau’s government ordered border police to avoid questions about an applicant’s military status, making it easier for AWOL soldiers to cross safely into Canada.

In the 1980s, however, the law was changed so that immigrants now must go to their local embassy or consulate to apply. And now residency can’t be granted on the spot. A long application process is generally the rule, during which time an applicant is expected to go about his business as usual in his home country. That prospect is not so simple for an AWOL soldier, obviously. Instead, soldiers—about 20 so far represented by War Resisters Support Campaign—are crossing the border as visitors and claiming refugee status, which is a much more difficult process, as illustrated by the travails of Hinzman and Hughey.

The rest of America’s AWOL soldiers—there have been at least 8,000 since the beginning of this war three years ago, according to documents recently released by the Pentagon—are either living underground or have been caught. The war resisters in Canada say they occasionally meet some when they are on speaking tours. “Most of them are probably waiting for a provision to be made for them to come out of hiding,” Pat says.

In the meantime, the Harts are basically living as though they’re Canadian citizens. They have access to the Canadian health system and Social Services, which, Jill says, “is not a goal, not something I want to do.” Being a former social worker herself, she understands the stigma attached to Social Services, but the Harts are in the midst of a lengthy process to get working visas.

After arriving in the country, they had to get physicals, X-rays and blood work to apply as refugees. Once that paperwork came back from Ottawa, they had to send working visa applications off to Alberta. They finally got their work permits in January, but they still need SINs (the Canadian equivalent of a Social Security Number) before they can get work.

They receive help from the War Resisters Support Campaign, the group that initially assured Pat of their support should he go AWOL. The Harts also do speaking engagements around the country, where they pass the hat. “We kind of live off the donations of the Canadian people,” Pat says.

“That’s what’s most important”

The Harts expect to be able to work by the end of this month. “We want to contribute to Canadian society,” Jill says. “We’re ready to get on with our lives and live as a family. And that’s what’s most important to me, living as a family.”

While it was probably the hardest decision he’s every made, and certainly the hardest time they’ve ever faced as a couple, it seems neither Pat nor Jill is looking back. In fact, Pat’s parents say he’s fallen in love with Jill all over again since they moved to Toronto. Whatever the Harts encounter in the future, it’s clear that they have each other.

“I took a vow to stand by his side, through good times and bad,” Jill says. “I’m not going to leave him alone in Canada during his first bad time. That’s not me, that’s not us.

“If you ever get the opportunity to see my husband interact with my son, I don’t have to say anything. It speaks for itself. It’s more important for me to raise my son right than to have a boxed flag on the wall and a picture I can show my son and say, ‘This was Daddy.’ We both strongly believe that if he were to deploy that would’ve been it. I know that Rian’s terribly proud of his father, as I am proud of my husband. We definitely did the right thing.”

To respond to this article send an e-mail to editorial@artvoice.com.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n10: Brave Hart (3/9/06) > Brave Hart This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue