Next story: A Poet in Buffalo

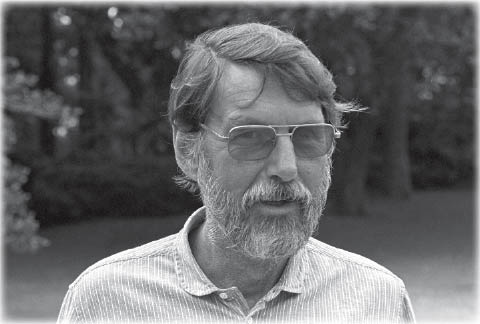

Remembering Creeley

by Bruce Jackson

Robert Creeley, who died in Odessa, Texas, on March 30, 2005, would have been 80 years old this coming Sunday. Many of his many Buffalo friends are getting together at the Church on Saturday evening and at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery Sunday afternoon to celebrate his life, his work and the nearly four decades he was vitally engaged in this city’s artistic and social life. He stayed involved with Buffalo even after he decamped for Brown University in 2003.

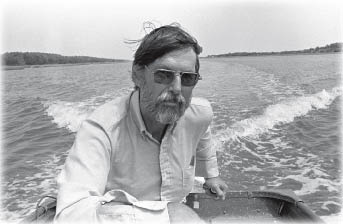

One of Bob’s favorite words was “company.” He was always talking about being part of a company—a company of family, of poets, of artists, of this group here on this night around this table, eating and drinking and talking, always talking. When the company constricts, so does your world, so do you. The first thing he said when we talked about Allen Ginsberg’s death in 1997 was “The company keeps getting smaller.” Company, for Bob, was whom you thought in terms of, whom you talked with. Like the narrator of what may be his best-known poem, “I know a man,” Bob Creeley was always talking. It was part of the great pleasure of his company.

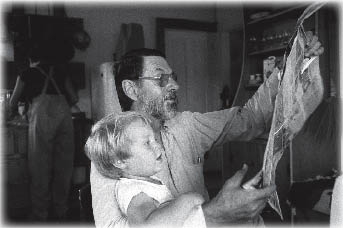

Bob surely found company and folks to talk with in Buffalo. Not one of all the terrific writers who came here as part of Al Cook’s legendary UB English Department in the 1960s was so much a part of Buffalo’s artistic life as he. During the years he was UB’s David Gray Professor of English and then Samuel P. Capen Professor of Poetry and the Humanities, he brought a steady stream of writer friends to town for readings and conversations. He was instrumental in the early years of Hallwalls and Just Buffalo, for which he gave readings, as he did for the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, the Burchfield-Penney Art Center and many other community organizations. He was active in his kids’ schools—City Honors for Will, where he helped set up their web-based writing system before anything like that existed at UB, and Buffalo Seminary for Hannah, which recently named a new eight-seat racing shell for him.

He was a prodigious writer. He published more than 60 volumes of poetry, as well as books of fiction and essays. The published version of his correspondence with the poet Charles Olson runs 10 volumes. When computers came in, he became an obsessive emailer. In his later years, he traveled with a small computer in his shoulder bag so he could connect with his friends any place there was the right kind of signal in the air.

He perhaps first came to wide public attention with his now classic collection of poems For Love: Poems 1950-1960 in 1962. His final book, On Earth: Last Poems and an Essay (“Reflections on Whitman in Age”), was seen through the editorial process by his wife Penelope and was published a few months ago by UC Press. University of California Press is publishing a two-volume set of his Collected Poems later this year, to be followed by new editions of his essays and fiction. Throughout his career he collaborated with such musicians and visual artists as Steve Swallow, John Chamberlain, Francesco Clemente, Jim Dine, Max Gimblett, Robert Indiana, Cletus Johnson, Alex Katz, R.B. Kitaj and Marisol.

Bob received many major awards, among them the Frost Medal, the Shelley Memorial Award and the $200,000 Lannan Lifetime Achievement Award. He was, noted the Lannan citation, “one of the founders of the Black Mountain school of poetry, which emphasized natural speech rhythms and lines determined by pauses for breathing—a poetry designed to transmit the poet’s emotional and intellectual energy directly and spontaneously.”

In 2001, some Texas friends of my son Michael started a DVD magazine called Substance-TV. Their plan was to assemble a wide variety of audio and video items every eight weeks or so: interviews with major artists, performances, documentary films, photos and so forth. For their first issue, they came to Buffalo to film Bob talking with me about poetry, art, words and other matters that concerned him. Their 17-minute edited version of that conversation, Robert Creeley: The Persistence of Verse, will be shown at the Albright-Knox Sunday afternoon. The full conversation along with an extensive bibliography of work by and about Creeley will be published later this year by UB’s Center for Studies in American Culture in their Working Papers series. Here are some extracts from that September 6, 2001, conversation.

BEING A POET

Bruce Jackson: What does it mean to be a poet?

Robert Creeley: It has no clarifying resolution whatsoever. A poet is a person who writes poems and poems are written by a poet. They both end at the same nowhere definition. To me, it’s someone who—let’s see, how can I put it—who not plays with, precisely, but who uses the material, uses words, which for me are the most humanly determined resource in the arts.

Let’s say that movement, dance, sound, music, visual art, all of these have a physicality which, and a source and a determination which, in some ways takes place along with whatever the artist’s information or imagination in each case may resolve. But I love the fact that poetry, all writing in words, is using a source that is human to begin with. It’s like being naked.

In one sense one might criticize it as being too internalized…but it to me is the crucial cutting edge or the crucial information of where the human imagination of the world concurs or finds place with the human fact of the world, where the two have the most ample opportunity of connecting.

WORDS

RC: Williams says, “But the words that came to me made solely of air. I regret most that there has come an end to them.” It’s an art which has only its own song, only its own imagination to sustain it. That’s why judgments of poetry are so awkward to make. One can say, “Well, I see this is happening in this poem, “or “It has four wheels or four heads,” or “This is or is not the case.” But the legitimacy of its being so, the rightness or wrongness of that fact in some further sense of social condition or need or judgment is—how people can say?

Williams said a poem is “a small or large machine made of words.” It’s something that can exist apart from the person that echoes still in the habits of being words, the fact of words, because that does have the tradition of all the uses that informed the words, all the materials that have thus conjoined in those words. All the times people have said, “yes” or “no” or “I love you” or whatever the phrase may be. People who are drawn to and find abilities to make sounds, to make forms, patterns that have integrity and thus can hold. “My love is like a red, red rose.” Who knows why that’s interesting? But it is.

NOW

RC: It’s a fascinating time in that it’s now both simple and practical to engage sound, image and words in a way that was unthinkable back in the ’40s and ’50s. Now one can with really pretty rudimentary information manage a page that has all of these elements interacting, as witness our own website—

BJ: —the Electronic Poetry Center.

RC: Which has its e-poems, its e-magazines, journals. It’s a whole new ball game. Hypertext, for example, and all its permissions and accommodations. Also the fact that materials can be published in this way, so much more actively and simply than they could be when one had to go through the classic eye of the needle, which was the, you know, the literary journal of that time and place, which, whatever its sympathies, couldn’t accommodate the needs in fact of the poets thus coming in. So either one started one’s own small modest mimeograph magazine and hoped 10 people would read it…

It’s a funny time. I would say it’s remarkably conservative in the sense that people are reflective and the basic disposition is reflective.

PAINTERS AND MUSICIANS

BJ: You’ve worked with so many painters and musicians, more than any other writer I know or know of. What has that done to your own practice?

RC: I guess it’s given me, I want to say, something almost akin to refuge at times. When it’s constantly sort of shifted or opened or given me variants for kinds of suppositions of proposal of “reality” that was of my own habit. It really brought me literally to see things differently.

I’m just fascinated by the fact if poets think with their poems, painters, artists thus think with their paintings. There’s not simply a vocabulary or information thus encoded in a simplifying way. But there is literally visual thinking.

I’ve had friends—like, I think instantly of Bryce Marden—who think visually. He had a terrific show at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston a few years ago in which he was asked to make selection of their holdings that he as a young man then at the Museum School in Boston had used to reference. It was a wonderful show. Among its particular terrific virtues was that it illustrated or made very clear that what a painter saw in a visual field was not necessarily what a—he wasn’t looking for mother, he wasn’t looking for a figuration that would define a content that could be taken away from it. He was seeing a field of correspondences and echoes and interactions that weren’t verbal at all.

It never went through that defining pathway. It was fascinating; it was very impressive. So that there are all manner of things. I think back to Alex Katz. The way he reduces a kind of dimensionality, or makes a surface be primary. The way he sees is fascinating to me…

Painters have always been terrific. They’re great company. Painters are excellent company, as are musicians. Musicians have the habit of company.

BJ: Musicians have to be in harmony.

RC: Well, I feel in a peculiar way that poets thrive in the same circumstance, that poets are always more interesting if they are more than one. Somehow if you do isolate them thus you strip them of a great deal of their power.

RHYME

RC: I remember talking to Robert Duncan years ago about various kinds of rhyming. His point was that one could have not only rhyming of sounds, like “June moon,” but that one could have rhyming of syntactical frames, of patterns of thought, all manner of conditions. So the question was what could be the interval between the instances? And how, if here’s the initiating “rhyme A,” how long can it be in time, physical time, until, say, the other foot, the other shoes falls?

BJ: I noticed in Life and Death at least it seems you’re using a lot more rhyme these days.

RC: Well, I’m backed up against the wall, so that loops and working in increasingly smaller areas of—what would you call it? I’m fascinated by the loop, things going round and round. There are classic loops, sestinas for example, or sonnet is an instance obviously, where “in my end is my beginning.” Where there is a kind of sense of that sort. I wanted a pattern that would let one come in and go out, and recur, that would be utterly recurring. That the last word of the poem could be the first word and go round and round. Because I felt that I wasn’t going anywhere. It wasn’t that I was frustrated or stopped by age…Things to do today were my primary interest, not things to do tomorrow but things to do here and now.

I think the whole imagination of hurrying on is really absurd, given lives have this obvious finite end, as though one were rushing to get everything done, like packing an ultimate suitcase. I was thinking of Wordsworth, “we lay waste our stores.” It’s sad that one should be so programmed. It really does remind me of the donkey with the carrot dangling on a stick in front of his nose.

BJ: There is no end to it.

RC: There is no end. We now work, I read in our paper a day or so ago, that we now work harder than any nation on earth.

BJ: More hours.

RC: And think of them as hours. If we didn’t think of them as hours, well wouldn’t have work, obviously, because the two go together.

BJ: Work. Do poets work? Is poetry work?

RC: Well, there are desperate attempts to say that they work. But as any poet would tell you, when it’s working, it isn’t work.

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and Samuel P. Capen Professor of American Culture at UB. Temple University Press will publish his book Telling Stories early next year.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n20: Robert Creeley: A Poet in Buffalo (5/18/06) > Remembering Creeley This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue