Falling in Love

by Cynnie Gaasch

There is nothing quite as satisfying as experiencing a substantial exhibition of works by a mature artist. It is still more of a treat if you find yourself falling in love with the artist’s work, and better yet if you have been loving the artist’s work for years. I predict most visitors to Petah Coyne: Above and Beneath the Skin, on exhibit through September 10 at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, will find themselves lost and falling—into her world, and in love with it. I first fell for the sculpture of Petah Coyne in 1993, as an undergraduate student at Hampshire College, when I had the opportunity to visit her studio in the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn, New York.

The passion with which Coyne speaks about life, art and her sculpture was empowering to me as a young artist. I remember her going on about the beauty of dried fish in Chinatown, which she collected and strung from the ceiling of her apartment. She later covered trees on Houston Street and East Broadway in New York with decaying (and stinky) fish. But her work—the power and strength of it all the time playing with the beauty and delicacy of it is outright seductive. Visiting her cavernous studio in a giant warehouse shared by fellow sculptors of giant works of art—William Tucker, Ed Smith and Lee Tribe—was inspiring. It was a full-out introduction to what it meant to be an artist, entirely consumed in the world of creation.

Curated by Albright-Knox senior curator Douglas Dreispoon, the exhibition has traveled to the Sculpture Center in Long Island City; Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri; and the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona before returning to Buffalo.

The exhibition at the Albright-Knox proves Coyne’s zeal for creation and infatuation with the beautiful and the ugly in the world around us. Her work is feminine and masculine at the same time. While her large sculpture (often more than eight feet tall) is covered with feathers and silk flowers, its heavy metal core is often visible. The sculptures are usually either black or white, with glimpses of red showing up only occasionally.

In black works, like Untitled #1103 (Daphne), the black feathers suggest a cunning crow and the flowers, usually roses, covered with black wax suggest decay. The curled wires stretching out of the top become the branches of a tree, and here is the mythical goddess in her long dress transforming into a tree, decorated and weathered.

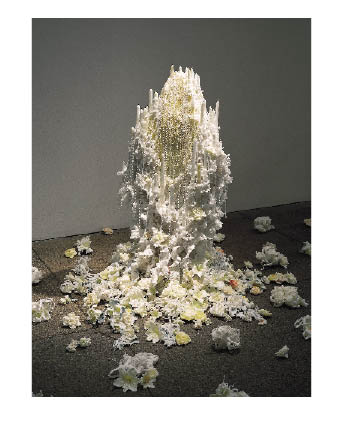

The series of white, chandelier-like sculptures made from 1994 to 1999 are like melting candelabras, baroque symbols of ritual. Coyne’s Catholic upbringing is often present in the imagery and titles of her work, as are other faiths. Untitled #1093 (Buddha Boy) is not as tall as many of her standing sculptures and actually suggests a young Buddhist. This sculpture is covered with white lilies, roses, beads and candles. Underneath the heavy headdress of candles, you can see a young face.

Most of these standing sculptures translate into people (mostly women) wearing elaborately decorated costumes, as if preparing for a ceremony of some sort. The figures always seem to be tied to the earth. The weight of these things is stunning—hundreds of pounds, requiring special moving cases to support the structures in transport. The weight reminds one of the actual weight of the costumes a celebrant might wear; Coyne is showing us the beauty of the world and its burdens.

The works of Petah Coyne are utterly about being female, as evidenced by a series of portraits represented in this show by a piece the Albright-Knox owns, Untitled #978 (Gertrude and Juliana, The Whitney Women). The piece is 12 feet tall and 18 feet wide. It is a wall made of drywall on wooden studs, open at the back. The side facing into the center of the gallery is painted white. There is a woman on either side of the piece, dressed in a saintly costume that reaches well past their feet, trailing across the floor. This piece was made for the 2000 Whitney Biennial and is a portrait of the sisters of the philanthropic Whitney family. On the backside of the sculpture the two women are more exposed, their arms and heads bleeding through the structure. The piece offers the public and private side of these women, and the their separate characters are described only in their gestures, relatively hidden from view.

A similar portrait was made for Marilyn Monroe, titled Untitled #983, Mary Marilyn and Norma Jean. This piece turns the iconic superstar into the mythic mother of God. Coyne told Ann Wilson Lloyd of the New York Times that the piece had “less to do with faith and more to do with humanity and being female in the world.” The figures, dissected by walls, certainly suggest the dichotomy of two worlds, and we can play with what these worlds are—private and public, protected and exposed, individual and stereotypical, sacred and secular.

Petah Coyne plays with perception and reality in her work. The reality is in the absolute presence of the sculptures. Perception is what the viewer brings to the works and reads into all of the symbols interlaced by the artist: birds, feathers, roses, candles, chain-link fence, chicken wire, wax, candles, hair, saints, nuns, monks, cocoons and webs. The real woman is in the strength; the perception is in how she is adorned. Embracing it all allows you to fall in love.

The exhibition at the Albright-Knox is paired with a small show of photography by the artist in the Collector’s Gallery, where the pieces may be purchased, through September 17.

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n32: Byron Brown on the Casino Deal (8/10/06) > Falling in Love This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue