Israel and Us

by Bruce Jackson

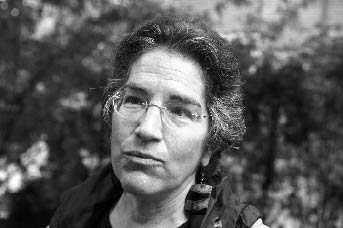

This conversation with Phyllis Bennis, a fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies and a widely respected expert on the politics of the Middle East, took place during her October 10-11 Buffalo visit. Bennis was in town to give a lecture at UB, “Palestine, Israel and the US after the Lebanon War,” and to meet for discussions with students and peace activists. Her visit was sponsored by the Western New York Peace Center’s Task Force for the Peaceful Resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, the UB Progressive Alliance and the Center for Comparative and Global Studies in Education.

Bennis is, according to the IPS, “also a fellow of the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam. She has been a writer, analyst and activist on Middle East and UN issues for many years. While working as a journalist at the United Nations during the run-up to the 1990-91 Gulf War, she began working on U.S. domination of the UN, and stayed involved in work on Iraq sanctions and disarmament, and later U.S. war and occupation in Iraq. In 1999 Phyllis accompanied a group of congressional aides to Iraq to examine the impact of U.S.-led economic sanctions on humanitarian conditions there, and later joined former UN Assistant Secretary General Denis Halliday, who resigned his position as Humanitarian Coordinator in Iraq to protest the impact of sanctions, in a speaking tour. In 2001 she helped found and currently co-chairs the U.S. Campaign to End Israeli Occupation. She works closely with the United for Peace and Justice anti-war coalition, and since 2002 has played an active role in the growing global peace movement. She is the author of Understanding the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict: A Primer, published by TARI and available in hard copy from IPS, text on-line at the website of the U.S. Campaign (www.endtheoccupation.org).” Some of her other publications are Before & After: US Foreign Policy and the September 11th Crisis (Interlink Publishing 2002); Calling the Shots: How Washington Dominates Today’s UN (Interlink Publishing, 2000); Beyond the Storm: A Gulf Crisis Reader (Interlink Publishing, 1991); Altered States: A Reader in the New World Order (Interlink Publishing, 1994); and From Stones to Statehood: The Palestinian Uprising (Interlink Publishing, 1990).

An independent think tank

Bruce Jackson: What is the Institute for Policy Studies?

Phyllis Bennis: The Institute is an independent progressive think tank in Washington, created in 1963 by two escapees from the Kennedy Administration—one from the White House and one from the State Department—who were dissatisfied with Kennedy’s positions on nuclear weapons, on Vietnam, on Cuba, on civil rights, on a whole host of issues. Marcus Raskin and Dick Barnett left the Kennedy administration and set up what was then an unprecedented idea of an independent think tank, not part of a university and not funded by the government or a corporation or something like that, but independent.

It’s gone though many different incarnations and different emphases, but they key to it is, it’s always been a center for linking ideas with action. So the scholars of IPS, who do writing and research and speaking and that sort of thing, do all of that work in the context of growing social movements and helping social movements articulate goals and strategies.

In the ’60s that meant that IPS was a key component of the civil rights movement. Civil rights activists came to the institute at various points for periods to work on articles and books. Later it’s played important roles in the women’s movement, in the anti-apartheid movement in the ’80s, in the anti-intervention in Central America movements of the ’80s, the Vietnam movement certainly throughout the ’60s and ’70s. It’s been a sort of component of those movements, but always independent.

BJ: Who funds it?

PB: Funding is very difficult. By charter, we can’t take government money or corporate money. Not that we’re being offered any, so that’s not much of an issue. But abstractly we can’t. The money comes from individual donors and from private foundations. It’s a constant struggle, particularly these days, when there’s a great deal of fear in the funding community. After 9/11 especially, the pressure is on not to fund anything having to do with the Middle East, certainly not to fund anything having to do with Palestine.

My work and our funding is basically project by project. The best funders are those who understand the importance of supporting institutions and what it means to build an institution. Most funders don’t get that. Unfortunately most funders want a specific project that’s going to result in a specific goal being met, a specific product or whatever. That means it’s a huge struggle.

The second superpower

PB: My project is called the New Internationalism Project, which basically is all the work that I do on Middle East and UN issues. My last book dealt with this issue in a more direct way, the idea of a new internationalism. I’ve been grappling with it in my own mind and in some of my writing for the last several years. The idea was that to create massive social change—which is what I think is required these days, not little incremental reforms here and there, but massive restructuring of the world and societies. It isn’t enough to talk about building stronger people’s movements. That’s the core; that’s the central part. But it’s not enough.

What I started looking at was, in the run-up to the war in Iraq, the global mobilizations of February 15, 2003. In 660 cities around the world, in this huge outpouring, the world says no to war. The Guinness Book of World Records says it’s the biggest single day of demonstrations in the history of humanity—of course, they say the history of “mankind”—with somewhere between 12 and 14 million people on the streets on the same day. An extraordinary event. And the next day the New York Times writes about it on the front page and says “Once again there are two superpowers in the world: the United States and global public opinion.”

That was huge. We all grabbed that line as a rhetorical line in speeches or whatever: “the second superpower; we are the second superpower.” It was very powerful, but in examining it a little more closely, I realized that what was really at stake here, and the reason that it had that impact—I mean, the Times got it not just because there were a lot of people, that had happened before, it would happen again, maybe not at that scale, but that’s an incremental issue—but that what was different was this was in the context of a much broader mobilization that was not only the people’s movements, the social movements, at the center, but also involved governments, who for their own reasons, usually quite opportunist reasons, were also coming out against the war. Eventually there were enough governments that the United Nations itself was forced to come out against the war. And it was that collaboration, the three parts—of the people’s movements, the governments and the UN—together that made up this phenomenon that we now call the second superpower.

That’s a lot of what my work is. It’s trying to link social movements with governments, UN with social movements, social movements with the UN. All of those intersections.

Not an academic

BJ: Unlike most of the people who write about these things, your pieces almost always end with an action component. You say what could be done, what should be done, where does this take us, rather than just looking at it.

PB: It is true that my writing is designed to be used by activists and by people in motion, whether in government or outside of government. But I’m not an academic, I never have been.

In my first effort to get a grant, before IPS, I tried to get a writer’s grant from a very large foundation that had a large research and writing program. I made it to the short list, and when I didn’t make it, they sent me the readers’ evaluation. There were five of them, and four of the five had all said the same thing: They said she’s a really good writer, she knows her stuff—this was to write my book about US domination of the UN—they went on and on, this was good and that was good. But she doesn’t seem interested in influencing the academic debate. Damn straight!

I resubmitted my application and I used lots of big words, a bibliography of books I had no intention of using to make it look academic, right? I still didn’t get it.

But I found that very interesting that that’s what they wanted. It was interesting because only that year they had opened up the program to non-academics, to journalists, and I was working as a journalist at the time. But apparently they hadn’t notified their readers that perhaps they should use a somewhat different standard, so they were still applying academic standards.

PNAC gets its “new Pearl Harbor”

BJ: Can you talk about the relationship between Project for the New American Century and Israel?

PB: “Project for the New American Century” was a paper that had its roots in a group of Washington neocons in the 1990s, who were not in power at the time. It was during the Clinton years. The paper was essentially a call to arms for a new vision of what the US role in the world should be. It posited a very extremist vision of absolute US domination on a global scale. It included language about how the US policy should be clear enough that no country or group of countries should ever even imagine that they could match, let alone surpass, US military might, that US military reach would never be met or answered by any other country. It was very unilateralist, highly militaristic; it called for privileging the Pentagon over the State Department, more money for the military, less money for diplomacy. It was a direct refutation of the idea that in the post-Cold War era, there should be something different in how the US operates around the world.

They presented it, as I understand, to the leadership of the Republican Party, which took one look at it and said, “Well this is all very nice but we could never get away with this.” It was basically put on a shelf until some unknown future time when, as they wrote in the paper, there was a famous line that said, “Probably this can’t happen until some huge event convinces people of the necessity of it, an event like a new Pearl Harbor.” That was the famous line in that paper.

And many people believe that for the Bush administration, September 11th was that new Pearl Harbor. You see language very similar to the language of the PNAC paper in the 2002 National Security Strategy document of the Bush administration that Bush announced just a few months after September 11th.

Support for Israel and an empowered Israel was a key component of how US power, in this definition, would be built. Several years later, in 1996, when he had just been elected prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu invited a group of the authors of that earlier paper to come to Israel to draft for him a strategy paper for Israel about what should be Israel’s role in the region. That paper, which was titled “Making a Clean Break: Defending the Real,” called for a very similar idea of what role Israel should play in the region. It’s what they had posited for what role the US should play in the world. So it should “make a clean break”—that’s what gave rise to the title—with the Oslo process. It should tell the Palestinians that they’re going to get what they’re going to get and the Israelis would decide what they were going to get, and this nonsense about negotiations was really over. That from now on the Arab countries surrounding Israel would be told that diplomacy would be conducted on a military basis from Israel rather than on a basis of negotiations. It was a very militarized vision of what Israeli dominance of the region would require.

As a result there’s this very enmeshed quality to the two papers, the PNAC paper and the “Clean Break” paper—not surprising, because they were written by the same people. Not all the same people, but they overlap; the people who wrote the “Clean Break” paper were overwhelmingly, I think, signatories of PNAC.

You get this question: “The neocons in Washington, are they more accountable to Israel than they are to the US?” There’s this anti-Semitism that creeps into it, that says, “These guys are more accountable to Israel than they are to the US and therefore they have dual loyalties,” that old canard. “It’s because they’re Jewish,” whatever. None of that, in my view, is really very relevant. Some of them are Jewish, not all of them. Some of them may be great fans of Israel on their own terms, but strategically their vision is that the United States’ assertion of power depends on a militarized, expansionist, nuclearized Israel. It’s very much tied to how they think US power is going to be built and consolidated.

BJ: This is the reverse of the way the relationship with Israel is usually perceived. That is, they are usually described as using the US essentially to enhance Israel’s power.

PB: You mean the neocons do that. I guess that’s true. The Israelis do in fact try to use the US to enhance their own power, but I don’t see that from the neocons. Theirs is a vision of the US on a global level.

Israeli reality

BJ: I heard you say that Israel looks upon itself in terms of Europe and the US rather than the Middle East, of which it is physically a part. Can you talk about the implications of that, both for the Middle East and for the US?

PB: In the US we grow up thinking Israelis are like us. Well, of course, half of them are from Brooklyn, so half of them are us. So there’s that. But aside from that, there’s a racist edge to that, because it implies that Israelis are white—because when Americans think of who are Americans, they think white, they don’t think of multicultural, multiracial, and so forth. They think white. They think it’s like Europe. They think it’s Jews like you or like me—that it’s white Ashkenazi Jews, European Jews. In fact, 65 percent of Israeli Jews are Arabs and another 15 or 18 percent are Slavs from Russia, and three or four percent are Ethiopian Jews. Then the rest are the white Jews, who the US tends to think, “That’s Israel”—because that was always the elite who they dealt with. The old Labor elite in Israel was Ashkenazi. The ambassadors have been, the powers that be, the arms dealers, all of them.

But it doesn’t reflect reality in Israel.

Part of the reason for the close alliance between the US and Israel that began during the Cold War, was this edge that, in this very volatile region filled with oil, it’s a meeting grounds for the three continents, all that stuff. We have good ties with the Saudis, they’re dependent on us for arms; we have good ties with the Jordanians, they’re dependent on us for everything; we have good ties with the Egyptians, they’re dependent on us for money; we have good ties with all those Arab rulers—but at the end of the day you can’t really trust them—they’re Arabs. There’s this racist edge that runs through it. The Israelis are like us. Them we can deal with.

So there’s a sense of camaraderie, and it gets described here as, “Well, that’s because they are a democracy and these other countries are not.” Yeah, well, we’ve had plenty of good relations with plenty of non-democracies. And Israel is only partly a democracy. For Israeli Jews it is a very lively and vibrant democracy, but if you’re not Jewish, not so much.

That perception about what is Israel plays a big role in the US, the identification of Israel with white and European.

The ersatz European

Outside Israel, it gets built up from three different vantage points.

One is, the elites are white Europeans. So somebody like Shimon Peres, the grand old man of Israeli politics, the only remaining one of his generation, he’s an old sort of European intellectual. That’s his own way of thinking, that’s his identification.

The younger elites, like Bebe Netanyahu, identify with the US. None of them identify with being Middle Easterners. They don’t identify with being Eastern; they identify with being Western.

Then there’s the question of the response to early on the Arab boycott, but later the series of wars and tensions between Israel and the Palestinians, between Israel and all the Arab states, Israel and Iran, Israel and Turkey, which is now being mollified to some degree. This was sort of the answer to it: Well, we don’t need to have trade and normal relations with all these folks, we’ll just jump over them and have normal relations with Europe. So there’s all these efforts, like the fact that Israel has trade relations with the European Union on the basis of an association accord that is exactly the same considerations as a member of the EU. So they get all the trade benefits as if they were a member of the European Union.

BJ: Which none of the Arab countries does.

PB: Which nobody else does. Only Israel does. Of course, now there’s been a struggle for the past several years, because they’ve actually been violating the terms of it. The terms are very specific; it says goods produced in Israel will get this special tax exemption. What the Israelis have been doing is exporting goods produced on the settlements, in Israeli settlements in the occupied territories.

It gets very sticky. The problem is—and this has been a longstanding campaign—the problem is that Germany and the Netherlands have refused, and they operate by consensus, they’ve refused to hold them accountable for the violations of the association accord. So even though it’s a specific violation of their own rules—it’s not even sanctions we’re talking about, it’s just making them abide by the rules—Germany and the Netherlands won’t do it. That’s been an ongoing struggle.

It means that they can have that identity in terms of trade, where their economic relations are all with the US and Europe. I mean, they export, arms in particular, to Latin America, to Asia, etc.

Then the third thing is Israeli culture. Israeli culture is framed by a Western identity. It’s cultural domination. It doesn’t mean that Iraqi Jews or the Yemeni Jews or the Moroccans don’t ever speak Arabic; they might at home. But for example, there really are two tiers of schools in Israel, there are the Arab schools and there are the Jewish schools. The Arab schools are for the Palestinians, not for citizens of Israel. The Arab Jews are not considered Arabs; they’re Mizrahai Jews; they don’t use the term “Arab.” So there’s a sense of denial of even their own culture.

Cultural dominance in Israel

Israeli culture was based on the idea of challenging the shtetl culture, the ghetto culture, challenging the image of the weak Jew who didn’t fight back, the victim, the diaspora Jew who was scorned. In the creation of Israel and the founding myths and all that, there’s a huge emphasis on overcoming all that legacy of the victim, the perpetual victim, the hunched-up, stooped-over intellectual. Instead it was this grounded in the earth, there was a socialist tinge to it, but it was very much about pioneering and farming and we’re going to reclaim the land and the tan sabra—

BJ: I remember those pictures of the beautiful girl in short shorts…

PB: And the sandals, right. And I remember the boys that were in short shorts and sandals. Paul Newman as Ari Ben Canin [in the 1960 film Exodus] did more to justify the expulsion of Palestinians…god love him for what he does now, but then, god knows, he probably had no idea.

So the cultural dominance in Israel has really focused on building what they consider an independent Israeli culture. But not with any recognition that they are in the Arab world, that a huge component of their population is Arab—the 20 percent who are Palestinian and the Arab Jews who make up the majority of the Israeli Jews.

It’s ironic really. Palestinian food has become the leitmotif of Israeli cuisine, such as it is. So falafel and tabbouleh—these are Israeli salads. For a while the advertising campaign for El Al had these beautiful Israeli flight attendants wearing traditional Palestinian thobes, the black dress with the beautiful embroidery on the chest. Where did that come from? It’s like, “That’s Israeli.” Excuse me: not quite. So there’s this identification with Europe that has also had this huge cultural impact.

BJ: We’ll wear it but we know who we are; we’re looking toward Europe, we’re not looking at Arabs, by whom they’re surrounded. What does that do as far as their relationships with their neighbors?

PB: In many ways it’s the result of their relations with their neighbors. I would be hesitant to say it’s the cause. From the beginning the Israeli elite has identified with Europe; that was where they got guns, was from France and Czechoslovakia. Later, after ’67, it was the US. So they’ve always had that identity.

Escaping to Israel

The Jews who come from the Arab countries—in some cases, not all—viewed themselves as escaping—escaping anti-Semitism, escaping whatever. In the case of the Soviet Union, of course, it wasn’t so much escaping anti-Semitism, it was escaping from a collapsing country where nobody knew what was going to happen, and the Jews were one of the few identifiable populations that had a direct way out. They were only allowed out if they went to Israel. There was a whole thing about that. A lot of them wanted to go to the US, but the US said, “No, no, we’re going to not let them, we’re going to make sure they go only to Israel.”

BJ: There were a lot of them who went to Israel and subsequently left.

PB: Right. If you look at the Ethiopian Jews, similarly, they weren’t coming to escape anti-Semitism, they were coming because the entire county was in the midst of a terrific famine, and they were the only ones who were getting visas. The Israelis will take Jews from anywhere. Their preference is white, educated, violin-playing surgeons, but they will take Ethiopian peasants if need be, if that’s all that’s available.

The resettlement agency that does the in-gathering of exiles on behalf of Zionism is a quasi state institution in Israel. They always have one country that is their target each year—the beleaguered Jewish community in Belarus or in Argentina or wherever are—and that’s the basis for their fundraising. One of the ironies is that back in ’90s—around ’98, ’99, something like that—they didn’t have a country that year. There was no country left where they could say, “This Jewish community is facing rising anti-Semitism, is in danger, we need millions of dollars to bring them all to Israel.” So what they did was to say, “This year’s focus is the ’Stans, the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union.” There were Jews in those countries, not a whole lot but there are some. Problem with it was there weren’t any great anti-Semitic campaigns going on. They admitted that but said, “There could be in the future. We’re doing our fundraising now in anticipation.” I would have thought, you can do that a couple of times but at some point you can’t do that anymore. But somehow they’ve come up with others.

But that notion of targeted fundraising that requires constant victimization, that needs victims…

Non-Jew Jews

Diane Christian: If you want to come to Israel, how do you prove you’re Jewish?

PB: They don’t very much. There was a thing, you know, should the men have to prove they were circumcised? The problem is, Muslims circumcise too. So that doesn’t necessarily prove anything. And lots of Christians do. Some Jews don’t. Some Reform Jews in the US—it’s not healthy, or they’re hippies or whatever.

There was a sort of scandal that happened with the Soviet Jews in 1990. That was the big year, over a million came. The estimates are that as many as half of them may not be Jewish at all. Some of them were non-Jews who were children and inlaws and whatever, big extended families. And some were people who just had nothing, no connection to being Jewish, but figured if they could say it, they could get out. I don’t remember how it worked out, but I know there were debates in Israel about having them have to go through ritual conversion. The women would have to do a mikvah, the ritual bath, and there were questions about the men having to go through some sort of little additional circumcision—maybe a little slice: not to take off anything, just to feel a little pain.

Non-democratic democracy

BJ: A while back you used the word “democracy” in regard to Israel.

PB: Israel is a democracy in many ways like the US was a democracy in 1962. Which was that it had all the political infrastructure of democracy—elections, parliaments, voting, citizenship rights—but a whole sector of the population is excluded from that. ’62 was before the Voting Rights Act.

But it is a little more complicated than that, because in Israel voting is one of the rights that is universal. All citizens of Israel can vote; that includes the non-Jews, including the Palestinians. Not on the West Bank and Gaza, of course, not even in East Jerusalem, which despite the fact that Israel claims to have annexed it, the Palestinian population of Jerusalem are allowed to vote only in local elections for city council and mayor, not in national elections.

But Israeli democracy is quite vibrant at the level of politics and parliament and all that. Palestinians have political parties, they run for office, they have the right to vote.

The difference is that rights in Israel are not determined solely by citizenship. There’s another category of rights that are known as “nationality rights,” and eligibility for those rights is determined on the basis of being a Jew or not being a Jew.

That goes to the question of what schools you go to, how much money your school gets—Arab schools get less money from the state than Jewish schools. Serving in the military—granted, most Palestinians are not going to want to serve in the military, given the roles the military plays in Israel, but there are huge privileges that accrue to veterans of the military, which includes almost all Jews, except for the ultra-orthodox, who opt out so they can study the Torah full-time. But nobody else is excluded from service other than the Palestinians. That means that Palestinians don’t have access to state-funded university scholarships, government-supported low-income home mortgages, a whole host of things. Non-Jews can’t buy land in much of Israel. There’s a whole host of things that are not about citizenship.

So when Israelis get very indignant when you talk about discrimination and say, “No, no, no, all Palestinians are citizens, everybody can vote. Everybody’s equal.” That’s all true. The problem is the society is built in a way that doesn’t limit its rights and privileges only to citizenship.

That doesn’t even address the question of the fundamentals of Zionism, which is thoroughly undemocratic in the sense of who can be a citizen and who cannot. As a Jewish state, that’s the whole question of who gets citizenship. I have the right, you have the right, to go to the Israel and say, “I want to be a citizen.” As much as they might squirm, we’ll get citizenship. Most of the time, I think there might be a few exceptions.

BJ: Meyer Lansky [a New York gangster, instrumental in the 1930s founding of the US national crime syndicate]. They denied Meyer Lansky.

DC: Pressure from the US, though.

PB: The idea that I had that right years before I set foot in Israel, when no one in my family had ever been to Israel…My grandfather ran away from the pogroms in Minsk in 1910. There’s a fundamental undemocratic theme to the settlements. Even aside from the questions of land theft and expulsion of the Palestinians who lived there. Put that aside, that’s a given. But even as an existing policy now, the undemocratic character of it is far more than this question of what happens in elections.

(Next week: Bennis discusses the settlements, the Israel lobby, apartheid, and hope.)

|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v5n48: Gray Anatomy (11/30/06) > Israel and Us This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue