Next story: This Land is Their Land

The Original Rappers

by Buck Quigley

Conversing with the dead in the Burned-Over District

All across Western New York, the month of March was going out like a lion in 1848. Under blotchy gray skies, the winds came whipping off Erie and Ontario, and down the slender Finger Lakes, bending the skeletal trees back and forth in the muddy ground. The agitated air roared through pine woods and whistled over bent and broken grasses in the marshlands. Occasionally, the wind fell still, but only briefly, as if catching its breath before continuing its tempestuous discourse.

In a small farmhouse in the little Hamlet of Hydesville, located 30 miles east of Rochester, the Fox family had endured their first winter there. New immigrants from Canada when they moved into the place on December 11, 1847, they paid little heed to the local rumors that it was haunted.

But for the past month the darkness of the night brought on an increasingly robust cacophony of strange sounds. John Fox, the respectable Methodist farmer who headed the household, had been trying, unsuccessfully, to calm the nerves of his superstitious wife, who heard in the chaotic bumps and thuds the sound of footsteps, or the loud thump of furniture being moved.

The noises reached a crescendo on the evening of March 31, when the whole family lit candles and prowled through the rooms, seeking answers. According to her signed testimony, Mrs. Fox prevailed upon her husband to check all the window sashes. He went from window to window, shaking them in the hope of reproducing the odd noises. Instead of isolating the source of the sounds, the rattling only added to the weird rhythm. It was then that Kate, their 11-year-old daughter, noticed something strange. For each shake of the sash, there came a reply. Two shakes, two raps. Three shakes, three raps, and so on.

Invoking a nickname for the devil that was popular in the day, the little girl said, “Mr. Splitfoot, do as I do.” She then clapped her hands together twice. In a moment, her challenge was answered with two distinct raps of mysterious origin. Not wanting to be outdone, Margaret, their 15-year-old, chimed in: “No, do as I do.” With that, she clapped, counting, “One, two, three, four.” Four pronounced thumps came immediately in response. They all stood frozen in puzzlement and fear. Finally, Kate offered a solution. “Oh, Mother, I know what it is. Tomorrow is April Fool’s Day, and it is somebody trying to fool us.”

Mrs. Fox considered the possibility, but then decided to offer a tougher question. She asked the noise to rap out her children’s ages, from oldest to youngest. The raps came in short bursts, accurately counting out the ages of her six children. There was a pause before three additional thumps were heard. She blanched to think of her youngest child, the little one that had died at age three.

“Is this a human being that answers my questions so correctly?” asked Mrs. Fox. There was only silence, and the soft murmurs of the wind. “Is it a spirit? If it is, make two raps.” Two raps came in reply. “Make two raps if you are an injured spirit.” Two loud thuds rattled the house. “Were you injured in this house?” The answer came strongly again in the affirmative.

As the questioning continued, it was established that the responses were coming from a 31-year-old man that had been murdered in the house, leaving behind a wife and five children, though his wife had also passed away in the intervening years. His remains were buried in the basement. The spirit was asked: “Will you continue to rap if I call my neighbors that they may hear it too?” Two strong knocks indicated that the answer was yes.

When the nearest neighbor, Mrs. Redfield, arrived, the girls were sitting up in bed, clinging to one another with fear. She expected to be amused by the preposterous scene, but when she witnessed the terror in their faces, she reassessed the situation. To her amazement, she experienced firsthand a repeat of the questioning and the otherworldly knocks that formed the responses.

She called her husband and other neighbors to the house. Mr. Redfield, Mr. and Mrs. Duesler, Mr. and Mrs. Hyde, and Mr. and Mrs. Jewell all arrived. They listened in utter amazement to the uncanny sounds that seemed to be emanating from the hereafter, telling the macabre story of the murdered man.

Mr. Duesler took the lead and began asking practical questions: “Can your murderer be brought to justice?” No response. “Can he be punished by law?” No answer. “If your murderer cannot be punished by the law, manifest it by raps,” Duesler directed. Two distinct raps let them all know that was the case.

More details came out. The unfortunate had been a peddler, murdered five years previously on a Tuesday at midnight—his throat cut with a butcher knife. He’d been robbed of $500 before his body was dragged to the basement of the Fox’s home and buried there. A few months later, when the ground had warmed sufficiently to permit it, excavation of the cellar turned up a few human bones. Attention focused on the two young girls, who had initiated this contact with the dead. When they were not present, the rappings always ceased.

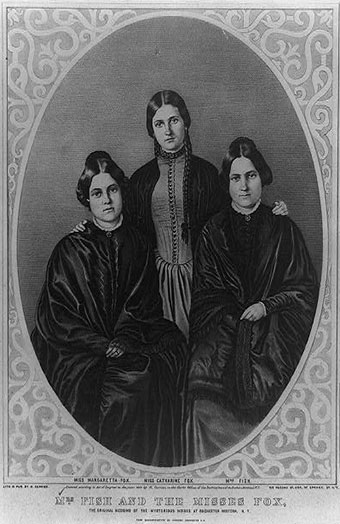

Thus, the Spiritualist movement was born. As news of Kate and Margaretta’s strange talent began to spread, an older sister, Leah, began managing their careers. Soon they were communicating with various personalities from beyond the grave in front of spellbound audiences as well as skeptics. The price of admission was the same for believers and doubters alike. Their fame spread rapidly, but had the two young girls been able to see into the future, it’s likely they would have chosen a different life path.

The Marvelous Child

Cora Lodencia Veronica Scott would become one of the most famous women of her time, both for her beauty and for her gift as a trance-medium. She was born in Cuba, New York, in 1840, where her father ran a lumber mill located between Cuba and Freedom. Ten years later, her parents would leave their Presbyterian faith to join the Hopedale Community, a Universalist group located in Massachusetts and then Wisconsin.

In the fall of 1851, 11-year-old Cora was sitting below an oak arbor in the garden of their Wisconsin home, preparing to work on a school composition on her slate board. She supposed she had dozed off. When she regained consciousness, her slate board was filled with someone else’s handwriting.

Figuring someone was playing a joke, she ran inside to show her mother and tell her what had happened. This surprised Mrs. Scott, because Cora’s little friends had come in moments before to report that she was “writing in her sleep.” Her mother took it for simple child’s play, until she looked at the slate.

“My Dear Sister,” the writing began. It was in the hand of Mrs. Scott’s sister, who had died when Cora was an infant. The deceased had signed the letter in her own distinctive handwriting. The girl had never seen nor could have known much of the sister. Shocked and frightened, her mother put the slate away, and said nothing to Cora about what the other children had told her.

Three days later, Cora was sewing at her mother’s feet when she suddenly slumped and fell fast asleep. Alarmed, her mother gently shook her, trying to rouse her to no avail. As panic set in, she saw Cora’s right hand begin to tremble and thought of the bizarre episode that had occurred just days before. As soon as a pencil was placed in her quivering fingers above a tablet, the little girl began to write very rapidly, jotting down a series of notes—each in its own distinctive script, signed by different deceased members of the family. Each one proclaiming, at the end of each message, “We are not dead.”

The messages also indicated that they would not harm the girl, but had found through her a way to communicate with those still on earth. Further, they wished for her to continue acting as their medium, for they longed to converse again with the living.

Every few days this phenomenon took place. There was no knowledge of Spiritualism in Wisconsin at the time, but gradually word of the miraculous episodes began to spread. Before long, the Scott’s house was crowding with curious neighbors who wanted to see Cora “writing in her sleep.” Friends as well as polite strangers began arriving to witness the events, and soon other spirits would move through her hand, writing notes to the new arrivals—messages from their own deceased ancestors. Gradually, the words from beyond began issuing directly from Cora’s own lips.

“Well, Ma,” her father said to his wife, “I have now found my religion.”

In the spring of 1852, she returned again with her family to visit relatives in Cuba. In similar fashion, she became a wonder for miles around. She began giving public addresses in school houses and town halls, as she’d also been doing in Wisconsin, astonishing ministers and other learned men with the impossible depth of her knowledge on philosophical matters.

Back again in Wisconsin, as her facility as a medium increased, she came to be controlled by an unnamed German physician while in a deep trance state. Several episodes were reported where Cora, not yet a teenager, visited sick or injured people and treated them with a degree of professionalism unheard of by the country doctors of the day—all the while speaking in a polished German dialect.

In the summer of 1853 she came back to New York State, but had only been there a couple days before her spirit guides told her she must return to Wisconsin. Her father, who’d planned on following them to New York, had fallen ill and died within days of her return.

Following his passing, Cora went back to Western New York and continued making public appearances in Dunkirk, Fredonia, and finally, Buffalo. After many spellbinding appearances at the private residences of the well to do, and at the fledgling First Spiritualists Society, she began attracting notice from the press. The incongruous sight of the pretty teenager with long springy curls delivering detailed discourses on arcane subject matter convinced many that her authority must be emanating from somewhere beyond this world.

In 1856, she married Benjamin Franklin Hatch, a professional hypnotist more than 30 years her senior. He brought her to New York City, where her fame exploded. At the height of her career, she toured constantly, appearing as far away as San Francisco and London, England. Hatch controlled and exploited Cora to a degree that would have made P. T. Barnum blush. He would spend large sums on lavish stage attire over lacy undergarments, but away from the footlights he was cheap, harsh, and rough. They went through a protracted divorce, which played out over six years in the papers. When it was final, Hatch still had thousands of dollars he’d made from her public appearances, and he spent it publishing pamphlets defaming her.

She remained popular. In 1886, in his novel The Bostonians, Henry James based the character of Ada T. P. Foat on Cora. The character is a trance-lecturer: “a lady with a surprised expression and innumerable ringlets.” The real-life Cora would go on to marry three more times.

Her last public appearance was in 1915 in Rochester. She died at her home in Chicago on January 3, 1923, at the age of 83. In her heyday, the uniqueness of her personality had prompted Walt Whitman to wonder, in a letter to a friend: “How are we to account for this fascination with Cora Hatch? And, a closely related question, what does this fascination tell us about American culture in the middle of the nineteenth century?”

The Burnt District

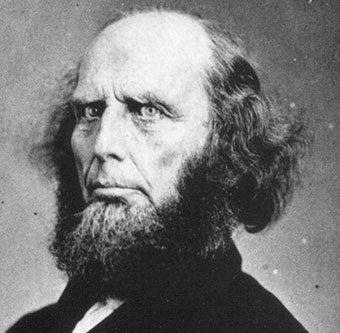

During the period of time known as the Second Great Awakening, Central and Western New York became a hotbed of new faiths. Back and forth across the new frontier, evangelists of all kinds traveled from place to place, bringing messages of salvation through tent revivals. Charles Grandison Finney, known as the Father of Modern Revivalism, coined the term. He referred to the “burnt district” of New York State, where so much of the population had already been converted that there wasn’t much fuel left to “burn” with the word of the Lord. Historians today refer to it as the Burned-Over District.

Aside from the more mainstream Protestant converts, the area also became home to several unique beliefs that could not find acceptance in stodgy New England. Among the first was Jemima Wilkinson’s. Wilkinson was brought up in a strict Quaker family. In October 1776, when she was 18, she was stricken with a severe fever for days, and she fell in and out of consciousness. When she awoke, she proclaimed she was now a holy vessel of God. She changed her name to “Publick Universal Friend.” Critics unfairly charged her with claiming to be a female version of Jesus. The Universal Friends built a settlement near Seneca Lake by 1789, calling it New Jerusalem. The Universal Friend practiced abstinence and is recognized as one of the first female religious leaders in America, and an early proponent of women’s rights. Her communal vision enabled her followers to be the first white settlers in the new wilderness, trading with the Native Americans.

A brief movement, if it could be called that since it had virtually no followers, emerged in Buffalo in 1825, led by Mordecai Manuel Noah. Noah believed that some Native Americans were Lost Tribes of Israel, and on September 2 of that year he led a large procession of Freemasons and city leaders to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, where a proclamation was read making Grand Island a homeland for Jews. The new Zion was to be called Ararat—the name of the place the Biblical Noah’s Ark came to rest after the flood. Nothing further took place, and Noah returned to New York City, where two years later he became the leader of the Tammany Hall political machine.

In 1822, a Baptist farmer named William Miller, who was an amateur student of the Bible, documented his conclusion that the second coming of Christ would occur in the year 1843. He did this by studying prophecies in the Book of Daniel, and using something called the year-day method of interpretation. After sitting on this knowledge for several years, he began sharing it with a few close acquaintances—some within the Baptist Church. Most were nonplussed. In 1832, he published a series of articles in a Baptist paper in Vermont, and began receiving letters and visits from curious believers. Eight years later, thanks to the widespread publication of his beliefs in the press, his doomsday predictions had spread throughout the Northeast, into Canada, and over to England. His followers were called Millerites.

As the end time drew closer, ecstatic followers urged him to focus his prediction. “My principles in brief, are, that Jesus Christ will come again to this earth, cleanse, purify, and take possession of the same, with all the saints, sometime between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844,” he told them. As that deadline neared, Miller further tweaked his prediction to April 18, 1844. When that date passed, it was thought that humanity was then going through a waiting period referred to in the Book of Matthew, before Christ’s return. By August of that year, as doubt increased among believers, another Millerite preacher crunched more prophetic numbers and came up with a date of October 22, 1844.

When that date came and went, some Millerites—who’d given away their earthly possessions in anticipation of the rapture—stopped working altogether. They reasoned that this protracted period of normalcy was akin to the Sabbath, and once that passed the end would really be at hand. Others began acting like children, pointing to Mark 10:15: “Truly, I say to you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God like a child shall not enter it.” Many simply shook their heads in disbelief and joined the Shakers. The period is referred to as “The Great Disappointment.”

From 1842 to 1855, a pietist group known as the Ebenezer Society planted roots in West Seneca and the Town of Elma on land purchased from an Indian reservation. They were also known as the Inspirationalists, or the Community of True Inspiration. Members were of German, Swiss, and Austrian descent. They eschewed military service and refused to take oaths, which set them at odds with German authorities. By 1855, they moved on to Iowa, where they founded the Amana colonies. There, they continued their communal life into the 1930s. One business that sprung from their work ethic was Amana Refrigeration, Inc.—makers of refrigerators, freezers, and, later, other household appliances like microwave ovens.

Saints and Sinners

Joseph Smith came from a family of drifters that landed in Palmyra, New York, in 1816, when he was 10 years old. A child of poverty, he came of age at a time when the frequency of religious revivals that would give the Burned-Over District its name was on the rise. His mother had the family changing denominations with each passing evangelist. At one such revival, Smith experienced a brilliant light, and claimed that God and Jesus had told him to believe in no religions, because they were all false. This set him apart. To some, he seemed something of a prophet. To others, he seemed a demented, dangerous zealot.

On September 22, 1827, the angel Moroni took him to a place on a hill near Palmyra, and showed him where the Bible of the New World was buried. Upon digging, he found a large stone box containing golden tablets carved with hieroglyphics Smith claimed were in the Reformed Egyptian language. They came with a set of crystals that worked like magic spectacles, and enabled him to translate the tablets, over the course of two years, into English. He did this with the help of four transcriptionists who wrote as Smith dictated from behind a curtain.

In 1830, with money provided by one of the transcriptionists, Smith published the Book of Mormon. Which, of course, is the genesis of the Church of Latter Day Saints.

There were many other visionaries that sprang from Western New York. In 1948, John Humphrey Noyes founded the Oneida Community, a commune that advocated Complex Marriage (a.k.a. Free Love). Noyes made his first theological discovery while a student at Yale, when he determined that the second coming of Christ had already occurred in 70 AD. At its peak, the community had about 300 members, but Noyes was forced to flee to Canada under threat of arrest for his unorthodox sexual practices.

He died in Niagara Falls, Ontario in 1886. The commune consolidated its various industries into the production of silver flatware. Oneida Limited became the biggest producer of silverware in the world for most of the 20th century.

The End of the Joke

Under their sister Leah’s management, the Fox sisters would go on to conduct popular public séances in New York City in 1850, attracting fans like William Cullen Bryant, James Fenimore Cooper, Horace Greeley, and Sojourner Truth. However, there were at least as many detractors. Over the course of time, various investigators claimed that the raps being heard were not issuing from the great beyond, but from underneath the girls’ long dresses. To true believers, this made no difference. And in this era of live performance, the curious continued to line up and pay the admission price to witness the paranormal displays. Some walked away laughing in scorn. Others walked away with their faith in the spirit world bolstered.

The heavy performance schedule took a toll on the young girls, however, and freed from normal parental supervision, they began drinking wine. As their fame increased, so did their alcohol intake. In time, they both married and had children. However, there was much resentment all around. Leah, now living in England as the wife of a wealthy man, complained of her younger sisters’ drinking and felt that Kate was an unfit mother.

Finally, with finances dwindling, Margaret made a shocking confession to the New York World on October 21, 1888. She described the Hydesville events that had occurred forty years previously. She explained that the mysterious raps were the result of the sisters cracking the knuckles of their toes. She further made this confession to a packed auditorium in New York, and gave a demonstration of the technique with Kate present, lending credence to the display.

Margaret recanted her confession a year later, but the damage was done. Shunned by all and desperately poor, they slipped rapidly into obscurity. On July 1, 1892, Kate died of alcoholism. Margaret followed the following March. Both died penniless, and are buried in Brooklyn, in the Cypress Hill Cemetery.

Final Words

In 1904, newspapers reported that children were playing in the “Spook House” in Hydesville when a false wall in the cellar fell down. According to William H. Hyde, the owner of the house at the time reported that the collapse revealed an “almost entire human skeleton.”

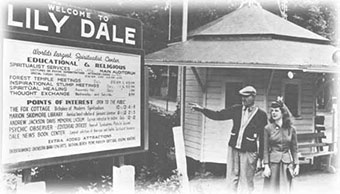

The house that gave birth to the Spiritualist movement was then moved to the grounds of Lily Dale, in Chautauqua County, “the world’s largest center for spiritual development and practice of the Spiritualist religion since 1879.”

The house burned to the ground on September 21, 1955, but the foundation, still intact in Hydesville, has been enclosed, and remains a stopping place for Spiritualists and curiosity seekers to this day.

blog comments powered by Disqus|

Issue Navigation> Issue Index > v9n42 (Halloween Issue: week of Thursday, October 21) > The Original Rappers This Week's Issue • Artvoice Daily • Artvoice TV • Events Calendar • Classifieds |

Current Issue

Current Issue